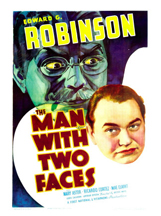

No slang we’ve encountered in an old movie caught us more offguard than the use of “groupie” in The Man with Two Faces (1934) , starring Edward G. Robinson, Mary Astor, Ricardo Cortez, Mae Clarke, and Louis Calhern, and based on a play cowritten by George S. Kaufman and Alexander Woollcott called The Dark Tower.

No slang we’ve encountered in an old movie caught us more offguard than the use of “groupie” in The Man with Two Faces (1934) , starring Edward G. Robinson, Mary Astor, Ricardo Cortez, Mae Clarke, and Louis Calhern, and based on a play cowritten by George S. Kaufman and Alexander Woollcott called The Dark Tower.

We’d long assumed that “groupie” was a product of the rock era, that it was coined to describe those women (and men, too, we suppose) who are willing to go that extra mile in demonstrating their devotion to a particular musician or band.

But a scene in THE MAN WITH TWO FACES suggests that the term might be much older.

In the film, Astor plays Jessica Wells, a troubled actress who was formerly married to a controlling creep named Stanley Vance (Calhern). Prior to the action depicted in the film, Vance had abandoned Wells, leaving her a total mess, her life and career in ruins. Finally, when word was received that Vance had died, Wells had slowly begun to pull herself together.

As the film opens, Wells is healthy and about to open on Broadway. Suddenly—wouldn’t you know it?—Vance appears on the scene, very much alive, and everyone close to Wells is concerned that she will crack up again.

In the pertinent scene, another actress (Clark) is sitting on Calhern’s lap as he flirts shamelessly with her. In walks a sardonic actor from the troupe (Robinson) who says, dismissively, “Well—a new groupie!”

Now, it’s possible he could be referring to Vance, since Clarke’s character is an actress and more likely to have an admiring fan, or he could—and I think this possibility the more likely one—be referring to Clarke’s character as Calhern’s groupie, without the fan/performer connotation we usually associate with the word.

Either way, we were surprised to hear the word uttered in a seventy-five-year-old movie. And our friend who works for the Oxford English Dictionary was, too.

“I’m very surprised to hear that the word is that early,” he told us when we mentioned the scene to him. “Every source I’ve ever seen puts it in the late ’60s.” The verdict’s not in yet—he’s still looking into the matter—but it appears that I might just have helped uncover what Jesse said could be “a major discovery.”

Now, it’s not as though we get a free copy of the OED for our contribution or anything (we live in Manhattan—who has room, anyway?), but we do get a kick out of the possibility that we may have contributed a cite that reveals a particular usage to be more than three decades older than was previously thought. We can’t really take any credit, of course—we were just indulging our interest in old movies.

But it’d be nice if our hobby actually provided a service. We leave our small marks in such ways as we can.