Regular Cladrite Radio readers know we love discovering unknown (to us, at least) bits of slang in old movies. Here’s an especially memorable one:

Regular Cladrite Radio readers know we love discovering unknown (to us, at least) bits of slang in old movies. Here’s an especially memorable one:

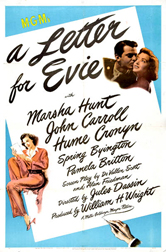

Some months back, we were watching Jules Dassin‘s A Letter for Evie (1946), a charming little “B” picture from MGM, and there was a scene wherein one soldier, a handsome hunk of a ladies’ man played by John Carroll, says to his new pal (Hume Cronyn), who is something of a bookish shrimp, “Let’s go out and pick up a couple of tomatoes.”

“Tomatoes?” asks Cronyn’s milquetoast.

“Yeah,” replies the man’s man. “Lollipops. Mice.”

Now, “tomatoes” we knew; “lollipops” we’d heard once or twice, but “mice”? That was a new one on us.

It was apparently new to Cronyn’s character, too; he puzzled over it, repeating it aloud a couple of times: “Mice??”

So we wondered if maybe it wasn’t coined especially for the movie.

So we wondered if maybe it wasn’t coined especially for the movie.

Nope, says a friend of ours, who happens to serve as North American editor of the Oxford English Dictionary. The use of “mouse” to refer to a young woman, he told us, “was very common in the 1940s. There’s a unique example from the late eighteenth century, but after that, it doesn’t turn up again until the late 1910s.” (To his credit, he also pegged, without us telling him, which movie we’d heard the term used in—he’s a whiz, there’s no denying it.)

We’re not sure it’s a usage that could be considered ripe for revival, but what the heck, it’s worth a try. we urge you to use it in a sentence sometime in the next week, even if whomever you’re speaking to is likely to be as confused by it as Cronyn’s character was.