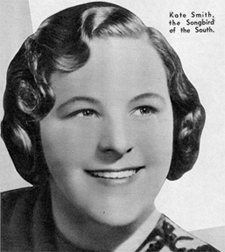

Most folks today who have any notion at all of Kate Smith think of her as a big gal with a big voice belting patriotic tunes in bombastic fashion. It’s hard to imagine her taking a pratfall, performing a soft shoe routine, or even offering a gentle rendition of a love song.

Kate Smith — “Maybe It’s Love”

But as is confirmed by this week’s edition of Snapshot in Prose, in her prime, Smith was a much more versatile performer than is recalled by most today. She was hugely popular, recording many hit renditions of the popular tunes of the day. And earlier in her career, she appeared in stage musicals, where she was respected as a comedienne and even a dancer (and no, she was not petite in those days).

This profile of Smith, from 1935, captures her at a point in her career when she has experenced great success and popularity but before she had become the sort of singing national monument she is now so widely thought to be.