If you’re at all like us (and honestly, who wouldn’t want to be?), the celebrity gossip of the 1920s, ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s is a lot more interesting than the blather that’s bandied about today.

If you’re at all like us (and honestly, who wouldn’t want to be?), the celebrity gossip of the 1920s, ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s is a lot more interesting than the blather that’s bandied about today.

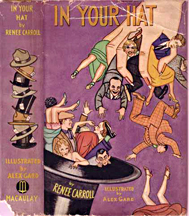

So we’re excited to share with you the introduction (contributed by Louis Sobol, a longtime Broadway columnist for the Hearst newspapers) and first chapter of a 1933 memoir by Renee Carroll, a woman who, in her role as hat check gal at NYC’s Sardi’s restaurant (and this is when Sardi’s was Sardi’s, friends), got to know the rich and famous (and occasionally even talented) on an intimate basis.

Even the title of the book, In Your Hat, has a gum-snapping sassiness that we like. And there are the celebrities who appear in the book: Ernst Lubitsch, Peggy Hopkins Joyce, Maurice Chevalier, Al Jolson, Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Flo Ziegfeld, the Marx Brothers, and so many more. And the illustrations throughout the book, rendered by Alex Gard. We think you’ll find this book a real treat.

Just consider it a loan from the Cladrite Library, and don’t fold the page corners to mark your place. Use a bookmark, for Pete’s sake.

In

Your

Hat

Introduction

RENEE CARROLL, a red-headed beauty, who smiles you out of your last quarter in exchange for a hat and coat which wouldn’t lure a quarter out of the most philanthropic pawn-broker in town, has written this book about the people whose names (and some of the names are awfully uneuphonious) hit you smack in the face every time you pick up a newspaper, stare up at a billboard or cluster of theater incandescents, or go into a huddle with other gossipy neighbors. In other words, it’s a book about celebrities, and take it from me, Renne knows her celebs.

RENEE CARROLL, a red-headed beauty, who smiles you out of your last quarter in exchange for a hat and coat which wouldn’t lure a quarter out of the most philanthropic pawn-broker in town, has written this book about the people whose names (and some of the names are awfully uneuphonious) hit you smack in the face every time you pick up a newspaper, stare up at a billboard or cluster of theater incandescents, or go into a huddle with other gossipy neighbors. In other words, it’s a book about celebrities, and take it from me, Renne knows her celebs.

I wish she hadn’t written this book. I wish she had gotten it together and then delivered it, paragraph by paragraph, to me. It would have made my daily task of columning such a simple thing. I turn green with envy at the names and the anecdotes she’s woven about them. Lubitsch, Peggy Hopkins Joyce, Maurice Chevalier, Harry Richman, Al Jolson, Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Lou Holtz, Lee Shubert, Flo Ziegfeld, Daniel Frohman—oh, what’s the use. Such names—such stories!

There’ll never be another book quite like this. I know of no one else in this town, and that includes the Broadway columnists, who has contacted the people of the stage and the screen and what was once known as Tin Pan Alley quite as closely or intimately as Renee of the flaming coiffure and the ingratiating smile. They drop their masks for Renee.

And Gard has drawn the illustrations. Gard, the cynical, whose crayon caricatures catch the soul of you. Cruel, grotesque caricatures, they but don’t, don’t mind that. Gard will tell you in that unaffected manner of his, “I draw you like that because I am loving you like a brother.” And then he’ll sharpen your ears and hook your nose and twist your lips but the likeness of you is there—and, as I’ve said, the soul.

Hats off, then, to Renee Carroll, for a grand book, and to her associate Gard for the pictures. I hope it’s the first of a series.

WHEN Arnold Rothstein, kingpin gambler, peeled that thousand-dollar note off his roll and threw it in my direction, I couldn’t quite make up my mind whether I was a success on Broadway or a failure in life. I don’t know today why he did it. Maybe because I wasn’t wearing any stockings, or maybe he felt that knowing a redhead might bring him luck in his much-publicized profession.

WHEN Arnold Rothstein, kingpin gambler, peeled that thousand-dollar note off his roll and threw it in my direction, I couldn’t quite make up my mind whether I was a success on Broadway or a failure in life. I don’t know today why he did it. Maybe because I wasn’t wearing any stockings, or maybe he felt that knowing a redhead might bring him luck in his much-publicized profession.We were at Tex Guinan‘s club. There were Tex and Tommy Guinan at the table, “Feet” Edson, one of Owney Madden’s mob; Jake Horwitz, a friend of Rothstein’s, and my girl friend. The reason for my presence was that I was supposed to be chaperoning my girl friend because she didn’t want people to be thinking that she was Jake’s woman. I don’t know how my being there made any difference in the situation because then people would be thinking that Jake was maintaining a harem on the Main Stem,—and we were two of the battalion. But that’s the way they figure things on Broadway, where “captive” is spelled “keptive.”

Rothstein was with two other mob members who made a hobby of floating crap games and body-filling dum-dums. It was early for him, I guess, only two in the morning, and he hadn’t begun his night’s work. Tex was pulling her usual fast line about suckers from the blue grass. Rothstein came over alone, leaving the other mugs waiting in a corner like two Boston bulls. All their hands were in their pockets, with knuckles making an ominous wrinkle in their skin-tight coats. You’ve got to have faith in a racket like theirs, and the trigger-ready rod each was fondling were not only faith but hope and charity, too.

“Hello, Arnold!” Tex greeted him. “Betcha three to two it rains before eleven this morning.”

“You’re a sucker for wet weather, Tex,” Rothstein smirked. “Aren’t you even Boy Scout enough to know that rain before seven means clear before eleven? It’s all over now.”

“Is it a bet?”

“Don’t be silly; I’m busy.”

Rothstein was looking at me. Suddenly he opened his Chesterfield overcoat and dug his hand deep down into his trouser pocket. He pulled out a roll of bills fat enough to choke Mrs. Astor’s pet whoozis. He peeled the top bill off the pile and casually tossed it on the table in front of me.

I couldn’t quite get the idea. Especially when I noticed that it was a $1,000 note—and real. A thousand dollars to me then was as big as Eddie Cantor‘s heart. It still is, as a matter of fact. But it was the first time anyone had shoved the United States mint right smack in my face. I looked up at the most glamorous gambler Broadway ever knew. He looked intently at me for a moment and then smiled.

“Could you go for one of these?” he asked quietly.

The other at the table suddenly became silent. It wasn’t every day that money-lender Rothstein loosened up with banknotes to a strange kid. I remembered vaguely that I’d heard somewhere about virtue being its own reward, but that kind of reward surely didn’t run as high as a thousand honest-to-goodness American dollars. For a minute I felt like the proverbial drowning person whose life goes flashing past in a few seconds. And plenty flashed by my memory’s eye that I wanted to forget. I remembered working at Roseland at a few cents a dance—and how many dances would make a thousand bucks, and how many dresses could I buy—and pounding that damned typewriter at thirteen bucks per with a fresh boss trying to make it fifteen if—and running away from home and living only a couple of blocks away from my folks for more than a year and never seeing them—and that hostess job in a Greenwich Village club—and walking the streets with a bun in my pocket to be saved for dinner because stenographers were combining talents and doubling in brass and keeping honest girls “at liberty.” A thousand dollars at my feet! I looked up at Rothstein, bewildered and just a bit frightened.

“Tell me when you’re ready to leave,” he said.

I don’t go in much for melodrama, but this was a situation worthy of a Broadway columnist’s best adjectives. I felt like a Bermuda surrounded by an ocean of silence. A notorious gambler had walked up to me, looked me over, and thrown down a sale price as if I were in a Macy showcase. Something went molten inside me. Maybe I’d seen too many movies. Maybe I didn’t like the look on the face of this czar of the underworld. I turned my shoulder on him and screwed up my face to what I thought was a crushing sneer.

I guess it was nothing new to Rothstein. He just bent over, picked up the bill, kissed it, and plastered it back on its brothers. Still no one said a word. Rothstein turned to go and then changed his mind. He turned with a child-caught-in-the-pantry look on his face and took out a roll of bills again. He peeled off another one and walking over to where I sat, he said:

“Just to show you I’m a good sport, buy yourself some diamonds—Woolworth’s.”

And without my realizing just what he was doing, he stuck a crumpled greenback far down the front of my evening dress. Then he turned and stalked out of the place with his two guardian gorillas.

Tex and the boys were still bewildered by what had happened, but without giving them a chance to ask questions, I hurried into the club’s dressing room. There I reached down for the crumpled currency and pulled it out into the glare of the incandescents. Hell, it was a one dollar bill!

Somehow I liked Rothstein for doing that. But I suppose the feeling wasn’t very mutual because he passed me at least a dozen times in night clubs after that, and I might just as well have been a Federal spy on his trail for all the attention he paid me.

My career as a hat check girl didn’t spring from that point, but it’s a good point for moralizing.The more I’ve seen of celebrities, the more I realize that what’s important in a life on Broadway is to keep your perspective wiped and clean. The minute that arms-length folds up and you get in up to your elbow, you realize that Broadway is the nation’s cardboard lover, a thin, anemic, romantic sort of guy with double padded shoulders, a trick mustache and soiled spats. It’s a small nation of “nice people” whose tastes are abnormal and who would rather whistle a line of patter that got printed in Winchell’s column than be Hoover in a high hat.

My advice, after years of rubbing worn elbows and accepting hats from moths of the bright lights, is to steer clear of the ribbers, keep your nose wiped constantly, and never mention Mammy to Al Jolson. If you’ve got bright yellow hair, wear orchids on your mink coat, ride in big mauve cars, have a voice that sounds as if it had been out all night, and your boy friend is a paunchy little guy who seems to need a shave all the time—and whose name is usually Louie or Nate, then you’re one of the mad mob, and you might just as well start lying to the folks back home about where the coat came from. If your shoulders are tailored like the roofs on a Japanese pagoda, you wear pearl-gray spats, tab collars and tie pins that make you look like a Slavic Prince of Wales, and you talk mostly with your hands, and your days begins at the crack of the evening mazdas flickering on, then you might just as well be wearing a uniform and marching in a parade labeled “Heel, Heel, the Gang’s All Here.”

Sardi’s, the restaurant at which I am ex-chequer of top pieces, is the Joe Zelli’s of New York. At Zelli’s they have caricatures lining the walls and everyone who comes to Paris goes to Zelli’s for a look at the celeb’s mugs. Nowadays everyone coming into New York, whether from Spodunk or Belleville, knows that every bright light in the bulb zone scoops up lunch or dinner at our place.

Sardi’s, the restaurant at which I am ex-chequer of top pieces, is the Joe Zelli’s of New York. At Zelli’s they have caricatures lining the walls and everyone who comes to Paris goes to Zelli’s for a look at the celeb’s mugs. Nowadays everyone coming into New York, whether from Spodunk or Belleville, knows that every bright light in the bulb zone scoops up lunch or dinner at our place.That’s how I came to be palsy-walsy with most of America’s theatrical great, and a regular elbow-rubber with the apples of your and your and your eyes. Sometimes, alas, the apples are unemployed.

That’s how I know that Walter Winchell has a zeal for veal, how Marlene Dietrich keeps those legs in the public’s eye, and where Ripley is going next to unearth those unbelievable “Believe It or Not’s”. Adolph Zukor talks to v and I know how the market will act in the morning, and Robert Montgomery goes a-courtin’ and I know that there’s every chance for a bassinet to be placed before Elizabeth Allen’s door. And sometimes I know the facts about those expectant bassinets even before Winchell does, and that’s as good as beating God to the draw.

Let me tell you about it.