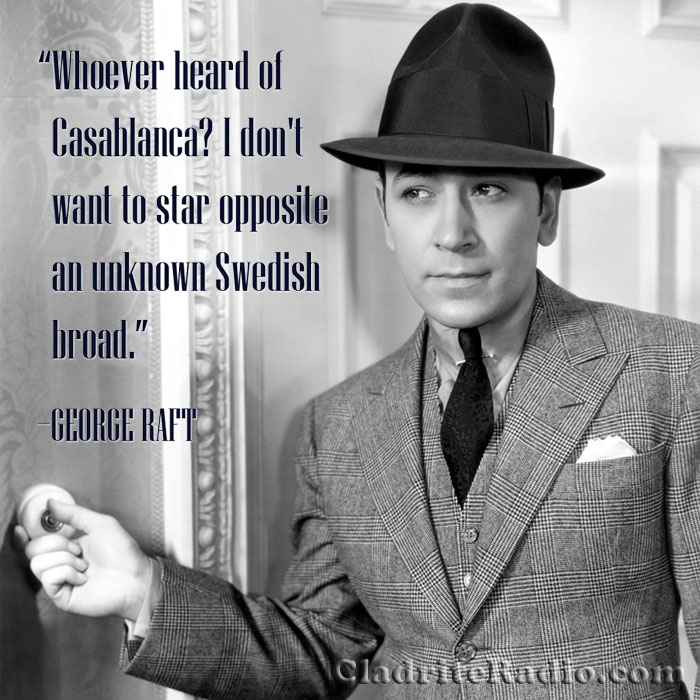

Actor George Raft was born George Ranft 115 years ago today in the Hell’s Kitchen section of New York City. Raft is perhaps as well known today for the movie roles he turned down as those he accepted. Here are 10 GR Did-You-Knows:

- His parents were of German descent.

- From his youth, Raft took a great interest in dancing, and his skills as a hoofer would serve him well as he found his way as a performer. In his salad days, he made money performing (and dancing with the lady patrons) at establishments such as Maxim’s, El Fey (with Texas Guinan) and various other night spots.

- He married Grace Mulrooney, who was several years his senior, when he was 22. They separated early on, but never divorced (perhaps because Raft’s family was Catholic), and he supported her until she died in 1970.

- Raft was known to run with a pretty rough crowd. He was childhood friends with gangsters Owney Madden and Bugsy Siegel; Siegel stayed at Raft’s home in Los Angeles when the gangster first moved there.

- Raft reportedly turned down the lead roles in High Sierra (1941), The Maltese Falcon (1941), Casablanca (1942) and Double Indemnity (1944). The first three of those roles proved to be great successes for Humphrey Bogart.

- Raft appeared in Mae West‘s first (Night after Night, 1932) and last (Sextette, 1978) pictures.

- In James Cagney‘s autobiography, the actor wrote that Raft prevented Cagney from being rubbed out by the mob. Cagney was president of the Screen Actors Guild at the time, and the story goes that he was adamant the Mafia wouldn’t become active in the union’s affairs, which was not a popular stance in certain circles.

- Raft was a lifelong baseball fan, attending the World Series for 25 years in a row in the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s.

- As a teen, Raft was a bat-boy for the New York Highlanders (later the Yankees).

- In the late 1950s, Raft worked as a celebrity greeter at the Hotel Capri, a Mafia-owned casino in Havana. He was there in 1959 when rebels stormed Havana to overthrow dictator Fulgencio Batista.

Happy birthday, George Raft, wherever you may be!