In Chapter 11 of his 1930 memoir, Vagabond Dreams Come True, Rudy Vallée had reached a point in his career that found him working all day long and sleeping no more than three or four hours a night.

As Rudy describes it below, he and his band had two rehearsals every morning, four live shows a day (five on Saturdays and Sundays) in a vaudeville theatre, and a steady night club gig that went from 11 p.m. till 3 a.m. nightly. Rudy also played a daily tea dance with a different, smaller ensemble backing him up and a dinner show as well.

Who ever said James Brown was the hardest working man in show business? In the laste 1920s, it might just have been Rudy Vallée.

Late to Bed—Early to Rise

BY THE TIME we were half-way through our vaudeville career I had aligned myself with the National Broadcasting Company completely. Before we began our vaudeville tour they held a broadcasting contact with me under which they broadcast me from the Villa Vallée with no cost to me or the club. Without my knowledge or permission I had been signed to play at a rival station which of course conflicted with my National Broadcasting contract. While we were at the Palace this had been litigated in court and on one occasion my appearance in court almost prevented me from getting to the Palace in time for our act. Every act there went on before ours and good old Van & Schenk dragged their act out as long as possible and stalled for me until I got there. Just before I went on, the manager gave me the good news of the judge’s decision: the National Broadcasting Company and I had won completely!

I knew that to be under the management of the National Broadcasting Company gave me a tremendous prestige and would in the end secure me better contracts than any other management could. The National Broadcasting Company secured my Paramount contract at double the figure I had hoped for. Four thousand dollars a week for eight men even for a few weeks was unheard of, but when we did twenty weeks and Paramount announced its intention of exercising its year’s option, the “I-told-you-sos” in the theatrical world who had predicted only ten weeks for us with Publix theatres were completely flabbergasted.

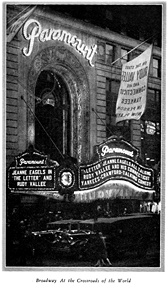

I knew that to be under the management of the National Broadcasting Company gave me a tremendous prestige and would in the end secure me better contracts than any other management could. The National Broadcasting Company secured my Paramount contract at double the figure I had hoped for. Four thousand dollars a week for eight men even for a few weeks was unheard of, but when we did twenty weeks and Paramount announced its intention of exercising its year’s option, the “I-told-you-sos” in the theatrical world who had predicted only ten weeks for us with Publix theatres were completely flabbergasted.I went home for one day with my folks before we began the Paramount contract, as I realized that I would not see them for a long time; and a few days later, with banners flying outside the New York Paramount, we began our contract with Public theatres. I still have pictures of the crowds in line and I was told that police were called out to keep the lines in place. And the cold figures giving us the house record made me very happy.

The presentation for the week we opened was put together especially for us and we did just a tiny part at the end of the program, so we were still very much a vaudeville act, but I looked forward to my second week when, with baton in hand, it was my duty to make the announcements and direct the big orchestra on the stage, gag with the acts, set the tempos, and then eventually step forward for my own spot.

The Paramount management was frankly only interested in Rudy Vallée, but I had told my boys that when I made money they would make it with me, and the only condition on which I agreed to go with Publix was that they use my band with me. I did not care whether my boys were absorbed into the large band or whether they came out on a rolling platform just to accompany me in my songs, but I insisted that my accompaniment come from my boys only. To this the management agreed, and then I was surprised to find my boys did not think they wanted to do it, inasmuch as they doubted their ability to stand up under the strain of two early rehearsals in the morning, four shows a day with five on Saturdays and Sundays, and work at the night club every night from eleven until three. My lot was considerably harder, though I enjoyed it.

I had tea dances at the Lombardy Hotel from four until six-thirty daily, including Sunday, and the dinner session at the Villa Vallée from 7:30 until 9:30. Obviously, our vaudeville made it impossible for my boys and me to play the full tea dance or the dinner session at the Villa Vallée, so at the Lombardy I formed an orchestra composed of six boys, which I called the Gondoliers, and which I had trained to play in practically the same style in which the Connecticut Yankees played. Over the air they sounded practically the same, as I had very excellent men who had substituted for some of my boys at one time or another and who knew our style.

Although I could not be present for the entire tea dance at the Lombardy or the dinner session at the Villa, yet by driving fast in an automobile from one engagement to the other, it was possible for me to put in an appearance varying from a half-hour to an hour at both; but I was forced to engage another band for the dinner session at the Villa Vallée.

While we were playing Keith’s Palace, a young man named Will Osborne met me at the stage door and asked me if I would listen to a little orchestra in which he was the drummer and leader, and which was playing at an Alice Foote MacDougall Coffee House. He had been using only one violin but had recently added a second violinist who, incidentally had at one time played for me in a band which I presented at Lake Placid. I realized that this new addition to his band would give it the same violin quality of tone that has made our orchestra distinctive on the air, and so I made it a point to listen to his orchestra and then suggested their engagement to the owner of the Villa Vallée, whose word was final in such matters. He was satisfied with their work and agreed to engage them to play during the dinner session.

Later on we even permitted this orchestra to broadcast from the club during the dinner session, for the same jewelry concern for which my boys and I had previously broadcast for more than a year.

My daily schedule was this: Usually I arose at ten, but if it was a rehearsal morning for the Paramount, it was necessary to get up earlier in order to be there at 9:30. On these rehearsal mornings I met the various acts, learned their routines and their gags (jokes), and rehearsed our own specialty. The unit or stage presentation usually began tat noon. After the second performance, somewhere around three o’clock, I jumped to the Lombardy where I sang for an hour and a half with the Gondoliers, then back to the Paramount for my third show. In my spare moments I listened to songs that various companies sent me to try out; read and answered letters; autographed photos; and then went on for the fourth show.

Immediately after this I hopped into a cab and went to the Villa Vallée where I sang with the Osborne orchestra. It was necessary for me to show this orchestra how to play after my own style, because I gave a peculiar style of singing against the beat which is very natural to me but which would throw the average band off if they were not instructed to hold the tempo, regardless of what liberties I took with the melody. Of course I also had to initiate the band into the way I played choruses in sections, how we changed from one chorus to another, the tempos themselves, and the signals that i flashed out to them with my right hand when I was not using it to play the saxophone. I stayed at the Villa Vallée until about 9:30 when I rushed back to the Paramount for my fifth and last show. Then I returned with my own Connecticut Yankees to the Villa Vallée to play from eleven until three. Thus I had very little rest and usually went to bed quite tired. Between every number it was necessary for me to go out and welcome friends and radio fan guests who ask the waiter to have me come over to say hello. Much as I love work, this was a grueling routine that most men would probably have cracked under, but I inherited a strong constitution, am very careful of what I eat, and I sleep well, when I have a chance to sleep, at no time have I ever felt the strain.

My boys did not find the Paramount work quite so difficult as they had anticipated, because in some of the presentations they did not appear until the last six minutes, and after that six minutes period, during which we played several tunes, they were free until the next show. True, they could go nowhere, and could only see bits of other shows. But considering the actual effort involved, they had never earned money quite so easily. They bought cots for their dressing-rooms, which took on the appearance of barracks, and spent the hours between shows in various ways.

Many people have wondered, I suppose, how I could be way over in Brooklyn at a theatre, broadcast from the Lombardy, be back at the next show in Brooklyn, and up to the Villa Vallée for dinner and fulfill all these engagements without splitting myself into three or four people. I have had to take some terrible chances in driving in order to make the various performances and I feel very proud of the fact that I have never missed a Paramount show or a broadcast. Once or twice I was late at the Lombardy for the broadcast, but I always managed to get in before the middle of the program was over to say “Heigh-Ho” and to sing a few songs.

Friday morning was a terrific strain on me as Master of Ceremonies because I retired at four or four-thirty from the club, arose at eight to be at the Paramount at nine where I rehearsed until twelve, when the first unit went on. I had to keep in mind every name, every tempo, and the order in which the acts came. Because of this loss of sleep, I could rarely give my very best to the first shows at the Paramount; and of course it would be only too tragic had I forgotten the name of an act, or cued them at the wrong time when they were not in the wings ready to go on. I had to think very fast when certain emergencies arose. Once or twice my tired mind did not register the name of the next act and I had to invent one. At another time I announced a certain act, turned around, gave the band introduction, but no act! We repeated the introduction but still the artists did not appear! Then I quickly went into my own specialty.

Once a very laughable thing happened. I announced an artist and pointed to the right, and like the old Mack Sennett comedies he came in from the left, leaving me in a very ludicrous position. However, such things as that touch my sense of humor and I am able to laugh them off. In one unit I turned around after announcing an act that immediately followed the chorus girls, to find that one of the girls had fainted on the stage and had been left there as the line danced off. I thought fast. Should I say that at last one of the girls in the chorus has fallen for me, or should I ring down the curtain, and should I simply carry her off. I decided on the last named procedure and lifted and carried her off, leaving the audience unable to comprehend it all, while the show went on as before.

There is a certain fascination about the stage, the footlights, the smell of the grease paint, the crowds and the orchestra. But I will not be sorry when this is all over, because after all, it is a very odd feeling that comes over me as I go to a restaurant or to a place of business between shows and realize that I must be back in costume, made-up and ready to go on in less than an hour and a half. A repetition of this procedure four times a day, five on Saturdays and Sundays, has broken the spirit of many men who did nothing but that, whereas I have also radio programs to be made up, work at the club each night, appointments between show with people who seek aid, both employment and financial, and who try to interest me in insurance investments, advertising propositions, and various other problems, so that I lead a hectic and busy life, and always of course I must be learning new songs and thinking of our own specialty, which has to be changed weekly.

Also, six performances and two matinees will seem such a relief after thirty performances a week! And to have Sunday nights off and to be able to sleep Sunday morning will be a blessed relief, because after all, this is the day of rest and has been set apart for that purpose, but the Publix theatres do not agree with the Powers above and believe that one should work harder on that day.

The Villa Vallée remained open all summer, as it was air-cooled just like the interior of the theatre, and was extremely comfortable to play in. Osborne had played the dinner session over a period of four months, but when I left to go to the Coast, the owner of the Villa Vallée made other arrangements and engaged Emil Coleman and his orchestra, which is very popular with New York society.

When I left for California, I said good-bye to the Paramount Theatres for a while, and it certainly felt strange to wake up in the morning and not wonder if I had overslept and missed the first show.