In Chapter 11 of his 1930 memoir, Vagabond Dreams Come True, Rudy Vallée had reached a point in his career that found him working all day long and sleeping no more than three or four hours a night.

As Rudy describes it below, he and his band had two rehearsals every morning, four live shows a day (five on Saturdays and Sundays) in a vaudeville theatre, and a steady night club gig that went from 11 p.m. till 3 a.m. nightly. Rudy also played a daily tea dance with a different, smaller ensemble backing him up and a dinner show as well.

Who ever said James Brown was the hardest working man in show business? In the laste 1920s, it might just have been Rudy Vallée.

Late to Bed—Early to Rise

BY THE TIME we were half-way through our vaudeville career I had aligned myself with the National Broadcasting Company completely. Before we began our vaudeville tour they held a broadcasting contact with me under which they broadcast me from the Villa Vallée with no cost to me or the club. Without my knowledge or permission I had been signed to play at a rival station which of course conflicted with my National Broadcasting contract. While we were at the Palace this had been litigated in court and on one occasion my appearance in court almost prevented me from getting to the Palace in time for our act. Every act there went on before ours and good old Van & Schenk dragged their act out as long as possible and stalled for me until I got there. Just before I went on, the manager gave me the good news of the judge’s decision: the National Broadcasting Company and I had won completely!

I knew that to be under the management of the National Broadcasting Company gave me a tremendous prestige and would in the end secure me better contracts than any other management could. The National Broadcasting Company secured my Paramount contract at double the figure I had hoped for. Four thousand dollars a week for eight men even for a few weeks was unheard of, but when we did twenty weeks and Paramount announced its intention of exercising its year’s option, the “I-told-you-sos” in the theatrical world who had predicted only ten weeks for us with Publix theatres were completely flabbergasted.

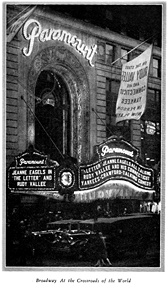

I knew that to be under the management of the National Broadcasting Company gave me a tremendous prestige and would in the end secure me better contracts than any other management could. The National Broadcasting Company secured my Paramount contract at double the figure I had hoped for. Four thousand dollars a week for eight men even for a few weeks was unheard of, but when we did twenty weeks and Paramount announced its intention of exercising its year’s option, the “I-told-you-sos” in the theatrical world who had predicted only ten weeks for us with Publix theatres were completely flabbergasted.I went home for one day with my folks before we began the Paramount contract, as I realized that I would not see them for a long time; and a few days later, with banners flying outside the New York Paramount, we began our contract with Public theatres. I still have pictures of the crowds in line and I was told that police were called out to keep the lines in place. And the cold figures giving us the house record made me very happy.

The presentation for the week we opened was put together especially for us and we did just a tiny part at the end of the program, so we were still very much a vaudeville act, but I looked forward to my second week when, with baton in hand, it was my duty to make the announcements and direct the big orchestra on the stage, gag with the acts, set the tempos, and then eventually step forward for my own spot.

The Paramount management was frankly only interested in Rudy Vallée, but I had told my boys that when I made money they would make it with me, and the only condition on which I agreed to go with Publix was that they use my band with me. I did not care whether my boys were absorbed into the large band or whether they came out on a rolling platform just to accompany me in my songs, but I insisted that my accompaniment come from my boys only. To this the management agreed, and then I was surprised to find my boys did not think they wanted to do it, inasmuch as they doubted their ability to stand up under the strain of two early rehearsals in the morning, four shows a day with five on Saturdays and Sundays, and work at the night club every night from eleven until three. My lot was considerably harder, though I enjoyed it.

I had tea dances at the Lombardy Hotel from four until six-thirty daily, including Sunday, and the dinner session at the Villa Vallée from 7:30 until 9:30. Obviously, our vaudeville made it impossible for my boys and me to play the full tea dance or the dinner session at the Villa Vallée, so at the Lombardy I formed an orchestra composed of six boys, which I called the Gondoliers, and which I had trained to play in practically the same style in which the Connecticut Yankees played. Over the air they sounded practically the same, as I had very excellent men who had substituted for some of my boys at one time or another and who knew our style.