In Chapter 11 of his 1930 memoir, Vagabond Dreams Come True, Rudy Vallée had reached a point in his career that found him working all day long and sleeping no more than three or four hours a night.

As Rudy describes it below, he and his band had two rehearsals every morning, four live shows a day (five on Saturdays and Sundays) in a vaudeville theatre, and a steady night club gig that went from 11 p.m. till 3 a.m. nightly. Rudy also played a daily tea dance with a different, smaller ensemble backing him up and a dinner show as well.

Who ever said James Brown was the hardest working man in show business? In the laste 1920s, it might just have been Rudy Vallée.

Late to Bed—Early to Rise

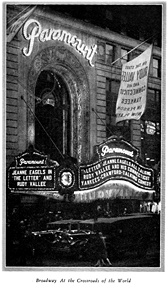

I knew that to be under the management of the National Broadcasting Company gave me a tremendous prestige and would in the end secure me better contracts than any other management could. The National Broadcasting Company secured my Paramount contract at double the figure I had hoped for. Four thousand dollars a week for eight men even for a few weeks was unheard of, but when we did twenty weeks and Paramount announced its intention of exercising its year’s option, the “I-told-you-sos” in the theatrical world who had predicted only ten weeks for us with Publix theatres were completely flabbergasted.

I knew that to be under the management of the National Broadcasting Company gave me a tremendous prestige and would in the end secure me better contracts than any other management could. The National Broadcasting Company secured my Paramount contract at double the figure I had hoped for. Four thousand dollars a week for eight men even for a few weeks was unheard of, but when we did twenty weeks and Paramount announced its intention of exercising its year’s option, the “I-told-you-sos” in the theatrical world who had predicted only ten weeks for us with Publix theatres were completely flabbergasted.