In Chapter 17 of his 1930 memoir, Vagabond Dreams Come True, Rudy Vallée regales the reader with tales of the songwriting game and music publishing business.

SONGS AND SONG WRITING

Along Tin Pan Alley the real song writer, in the accepted sense of the word, is he who has not only one or more hits to his credit, but whose mind is continually filled with lyrics and melodies and who can write a song almost at command. Of course it is greater proof of this gift to have five or six or even more successful hits to one’s credit; but the man whose mind is prolific enough to produce one song after another that will be at least moderately successful, if not a terrific hit, is the veteran song writer.

Along Tin Pan Alley the real song writer, in the accepted sense of the word, is he who has not only one or more hits to his credit, but whose mind is continually filled with lyrics and melodies and who can write a song almost at command. Of course it is greater proof of this gift to have five or six or even more successful hits to one’s credit; but the man whose mind is prolific enough to produce one song after another that will be at least moderately successful, if not a terrific hit, is the veteran song writer.

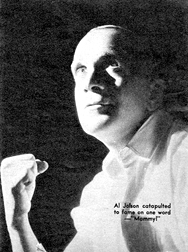

“MAM-MY! Mam-my!” boomed the great, heart-to-heart voice of Al Jolson, and the whole world shouted, “Here I is!”

“MAM-MY! Mam-my!” boomed the great, heart-to-heart voice of Al Jolson, and the whole world shouted, “Here I is!”