AMERICA’S SWEETHEART

His real name is Herbert Prior Vallee. Took the name of Rudy from Rudy Wiedoft, the saxophone player. His idol.

His real name is Herbert Prior Vallee. Took the name of Rudy from Rudy Wiedoft, the saxophone player. His idol.

AMERICA’S SWEETHEART

His real name is Herbert Prior Vallee. Took the name of Rudy from Rudy Wiedoft, the saxophone player. His idol.

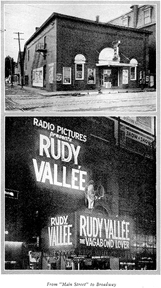

His real name is Herbert Prior Vallee. Took the name of Rudy from Rudy Wiedoft, the saxophone player. His idol.In Chapter 16 of his 1930 memoir, Vagabond Dreams Come True, Rudy Vallée recounts his earliest experiences in the recording studio.

IT’S IN THE WAX

The authorities of the University of Maine were interested enough in my musical efforts to allow me the use of some of the buildings on the campus for my practice. The agricultural part of the college had a large building known as Agricultural Hall where one learned all the science of the soil and animal life of the farm and barnyard. High up on the fourth floor were large classrooms that were empty at night. In one of these I used to practice certain very disagreeable sounding exercises. For instance, for the development of saxophone tone I started with the lowest note on the sax and held it as long as the deep breath I had just taken would permit. I have held certain notes of the saxophone for two minutes.

The authorities of the University of Maine were interested enough in my musical efforts to allow me the use of some of the buildings on the campus for my practice. The agricultural part of the college had a large building known as Agricultural Hall where one learned all the science of the soil and animal life of the farm and barnyard. High up on the fourth floor were large classrooms that were empty at night. In one of these I used to practice certain very disagreeable sounding exercises. For instance, for the development of saxophone tone I started with the lowest note on the sax and held it as long as the deep breath I had just taken would permit. I have held certain notes of the saxophone for two minutes.In Chapter 15 of his 1930 memoir, Vagabond Dreams Come True, Rudy Vallée pays homage to the man who served as his saxophone mentor and muse, Rudy Wiedoeft.

THE SAX GOD—WIEDOEFT

I took up the study of the trumpet while working back stage with a stock company, and then rented a saxophone when I began my senior year in school. The similarity between saxophone and clarinet made it possible for me to play a limited range of notes on the saxophone. The horn that I had was called a C Melody, being pitched in C. I could read song sheets, the violin parts, without any transposition. I used to play at night with several acquaintances who gathered in a bowling alley where near beer was served, and go canoeing with a banjo player or a violinist. Always I played for my own amusement and for those who cared to listen. Finally I was engaged by a small dance orchestra playing two nights a week in a Pythian Temple Building. This led to more engagements in northern Maine with what had been Maine’s most famous dance orchestra, Welch’s Novelty Orchestra.

I took up the study of the trumpet while working back stage with a stock company, and then rented a saxophone when I began my senior year in school. The similarity between saxophone and clarinet made it possible for me to play a limited range of notes on the saxophone. The horn that I had was called a C Melody, being pitched in C. I could read song sheets, the violin parts, without any transposition. I used to play at night with several acquaintances who gathered in a bowling alley where near beer was served, and go canoeing with a banjo player or a violinist. Always I played for my own amusement and for those who cared to listen. Finally I was engaged by a small dance orchestra playing two nights a week in a Pythian Temple Building. This led to more engagements in northern Maine with what had been Maine’s most famous dance orchestra, Welch’s Novelty Orchestra.In Chapter Ten of Rudy Vallée’s 1930 memoir, Vagabond Dreams Come True, Rudy relates tales of a ten-week tour that covered a half-dozen vaudeville theatres scattered across New York City, in every borough save Staten Island. Rudy and his band even played the very top theatre in all of vaudeville, the Palace.

The band’s radio audience turned out in droves to see them do their stuff in person, and Rudy could tell the tour was a big success, thanks to what he describes as “the telepathic interchange of appreciation with which the air [became] charged.” (We know, we know—it had us scratching our heads, too.)

Vaudeville

While this was still in the air I read in the monthly magazine of my fraternity, Sigma Alpha Epsilon, that Lawrence Schwab, the first half of the great musical comedy producing team, Schwab and Mandel, was a fraternity brother of mine, that he had struggled for recognition as a boy and now was perhaps America’s foremost producer of intimate musical comedies, and that in “Good News,” that latest Schwab and Mandel effort, they had used George Olsen. Olsen, however, was in Ziegfeld’s “Whoopee” and would not be available should they desire his services in the near future, so I approached Mr. Schwab, hoping to convince him that we might be useful in one of his future musical comedies. I told him that I did not wish to presume on our being fraternity brothers, but I did feel that we had something different to offer which, spotted in one of his musical comedies, might prove of value to him.

While this was still in the air I read in the monthly magazine of my fraternity, Sigma Alpha Epsilon, that Lawrence Schwab, the first half of the great musical comedy producing team, Schwab and Mandel, was a fraternity brother of mine, that he had struggled for recognition as a boy and now was perhaps America’s foremost producer of intimate musical comedies, and that in “Good News,” that latest Schwab and Mandel effort, they had used George Olsen. Olsen, however, was in Ziegfeld’s “Whoopee” and would not be available should they desire his services in the near future, so I approached Mr. Schwab, hoping to convince him that we might be useful in one of his future musical comedies. I told him that I did not wish to presume on our being fraternity brothers, but I did feel that we had something different to offer which, spotted in one of his musical comedies, might prove of value to him.