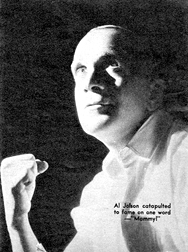

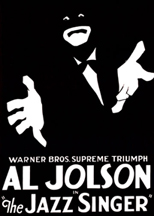

We’re of the opinion that no performer’s appeal has dropped as much over time as Al Jolson‘s.

By that we mean, given what a huge star he once was, it’s intriguing how dated and, well, odd he sounds to many people today.

Not that any other performers who became stars in the first three decades of the 20th century are moving many records (or mp3s) these days, but Jolson, to our ears, stands nearly alone among the stars of that era as a not terribly easily acquired taste for 21st century listeners.

This profile, first published in 1934, reviews Jolson’s rise from a hardscrabble childhood to unparalleled stardom. Give it a read, and see if you’re won over. And when you reach the end, we’ve included a pair of Jolson recordings for your consideration. “Sonny Boy,” especially, is Al at his most … emotive.

“MAM-MY! Mam-my!” boomed the great, heart-to-heart voice of Al Jolson, and the whole world shouted, “Here I is!”

“MAM-MY! Mam-my!” boomed the great, heart-to-heart voice of Al Jolson, and the whole world shouted, “Here I is!” Now that the little fellow’s tummy was gratefully full, he suffered the pangs of another hunger. It was for high adventure, a restless craving for romance.

Now that the little fellow’s tummy was gratefully full, he suffered the pangs of another hunger. It was for high adventure, a restless craving for romance.

We have some big news for you, straight from Cladrite Industries’ central office in the heart of New York City:

We have some big news for you, straight from Cladrite Industries’ central office in the heart of New York City: Anyone with a casual interest in classic movies knows that

Anyone with a casual interest in classic movies knows that