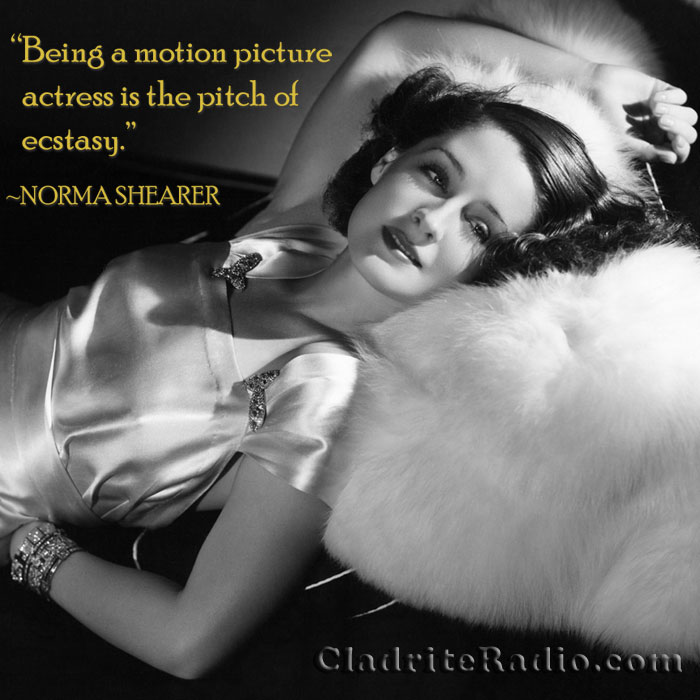

There seems to be widespread confusion regarding Norma Shearer’s birthday. Some sources say she was born on August 10, some say August 11, and The New York Times, in its obituary for her, cites August 15. The year is in question too: Was she born in 1900, 1902 or 1904? Biography.com lists her birth as occurring in 1900 and 1902.

We’re going with August 10, 1900, but we cannot promise that’s correct….

Norma Shearer was born Edith Norma Shearer 114 years ago today in Montréal, Québec, Canada. Here are 10 Did-You-Knows about the former Queen of MGM:

- Shearer, who won a beauty contest at 14, moved to NYC with her (stage) mother and sister Athole (who would later marry legendary director Howard Hawks) four years later. After Florenz Ziegfeld passed on casting Shearer in his Follies, she got some small roles in movies.

- Irving Thalberg saw some of her early movie work and in 1923 signed Shearer to a contract with with Louis B. Mayer Pictures, a precursor of MGM, where he was vice-president.

- Shearer made eight—count ’em, 8!—feature pictures in 1924.

- Shearer converted to Judaism to marry Thalberg in 1927 and continued to observe the faith after his death and for the rest of her life.

- Norma’s brother, Douglas, won twelve Academy Awards for his work as a sound designer. The pair were the first brother-and-sister tandem to win Oscars.

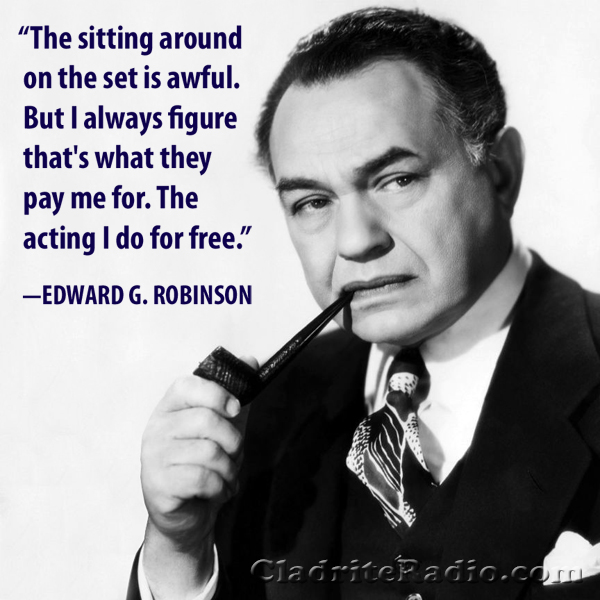

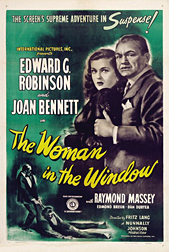

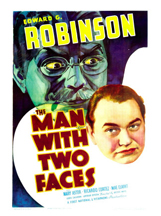

- At a point in her career when she appeared in only prestige productions, she played a part in The Stolen Jools (1931), a star-studded short subject intended to raise money for a tuberculosis sanatorium, as the owner of the titular “jools.” Also in the film were such luminaries as Wallace Beery, Buster Keaton, Edward G. Robinson, Laurel and Hardy, and members of the Our Gang cast.

- F. Scott Fitzgerald is said to have based one of his stories, “Crazy Sunday,” on one of Shearer’s parties and the story’s protagonist, Stella Calman, on Shearer herself.

- Weak eye muscles gave Shearer a slightly crossed eye; she worked with eye doctors to improve it and cameramen to disguise it.

- She was the third woman to win the Best Actress Oscar and the second of three consecutive Canadians to win it (Mary Pickford won it in 1929 and Marie Dressler in 1931).

- Among the roles she is reported to have turned down were Scarlett O’Hara (Gone with the Wind), Mrs. Miniver, and Norma Desmond (Sunset Boulevard). Of Scarlett, she said, “Scarlett O’Hara is going to be a thankless and difficult role. The part I’d like to play is Rhett Butler.”

Happy birthday, Norma Shearer, wherever you may be!