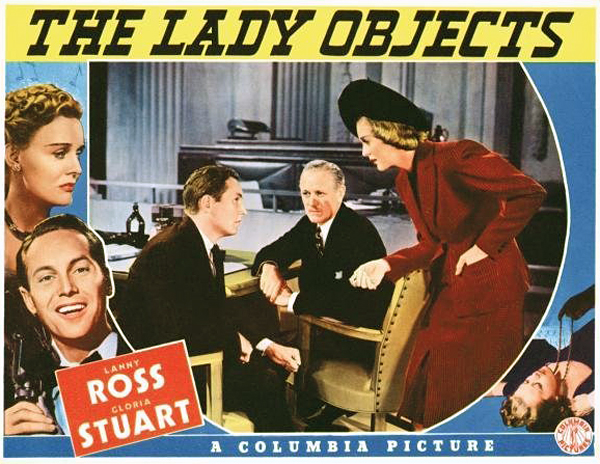

Last night we watched The Lady Objects (1938), a strange and kind of silly drama/musical (drusical?) that finds Gloria Stuart, adorable as ever, playing a hotshot lawyer whose husband (Lanny Ross), a former All-American halfback, a world-class tenor and a hopeful young architect (quite the trifecta, that), resents her success and the demands it places on her time.

As we said, kind of silly, but entertaining enough, since we get a special kick out of watching any picture that features Ms. Stuart. We were pleased to do a telephone interview with her some years ago when her memoir was published, and we’ll admit to being not a little proud that when we got to meet her in person a few weeks later at her book party in NYC, she flirted with us just the slightest bit. Nothing overt, nothing untoward, but in a room filled almost entirely with the young women of the publishing industry, we stood out, it seems—a young(ish—we were 41 at the time) man who was thrilled to dote on Ms. Stuart, bringing her food and drink, asking her questions about her movie career back in the 1930s and generally behaving in starstruck fashion.

So whenever we see her looking so fetching on the screen, we can’t help but think, That gorgeous movie star once flirted with us, an actress who might have once flirted with Humphrey Bogart, The Marx Brothers, James Cagney, Lee Tracy, Melvyn Douglas, Boris Karloff, Ralph Bellamy, Pat O’Brien, Eddie Cantor, John Boles, Claude Rains, Lionel Atwell, Frank Morgan, Brian Donlevy, Warner Baxter, Dick Powell, Frank McHugh, Don Ameche, Lyle Talbot, George Sanders, Walter Pidgeon, Jack Oakie, and Richard Dix. In any case, she appeared in pictures with each of them (except Bogart and the Marx Brothers, whom she knew socially).

Yes, our brief encounter with Ms. Stuart came more than a half-century after those hypothetical Hollywood flirtations—she was 89 at the time—but if she batted her eyelashes at even one-tenth of her aforementioned costars back in the day, we’d have to say we’re in pretty good company!