Charles Ray was a popular juvenile film star for the Thomas Ince studio in the 1910s who eventually broke away to form his own production company so that he might break away from the rural youth roles in which he’d been typecast. His 1923 production, The Courtship of Myles Standish (1923, now considered a lost film), was an expensive bust, and Ray lost everything.

Charles Ray was a popular juvenile film star for the Thomas Ince studio in the 1910s who eventually broke away to form his own production company so that he might break away from the rural youth roles in which he’d been typecast. His 1923 production, The Courtship of Myles Standish (1923, now considered a lost film), was an expensive bust, and Ray lost everything.

Ince helped Ray get back on his feet by offering him some roles, but Ince’s death in 1924 forced Ray to resort to working in low-budget “Poverty Row” productions, and he had trouble finding a niche after the advent of talking pictures. In the 1930s, he settled for minor, unmemorable roles to pay the bills, and launched various other endeavors, among them the Beverly Ray Cultural School (located at 5537 Hollywood Blvd. and named after Ray’s wife), where Ray promised prospective students he would “personally analyze your talent and chart a practical program for you.”

In 1936, Ray began publishing Charles Ray’s Hollywood Digest, a compendium of Tinseltown-related “stories or story excerpts, a full page of knock knock jokes, puns, odd, random facts or trivia, recipes, small film reviews, cartoons, etc.” (The Daily Mirror). The cost of the 96-page first issue was 40 cents (a 13-month subscription could be had for $5). And that issue featured an advertisement for Hollywood Shorts, Ray’s book of short stories (it could be had for a mere $2.50).

Sadly, there was to be just one more issue of Hollywood Digest. Thereafter, Ray continued to muddle through playing only occasional small roles in pictures until his death in 1943 of an infection caused by an impacted tooth. Ray was 52 years old and all but forgotten.

But we remember him. And we’re pleased to bring, on a weekly basis, the stories from Hollywood Shorts.

“A baby! A baby” the director demanded. “We’ve got to have a cute baby. It’ll make the picture!”

“Get a baby,” the assistant commanded of the casting office.

Mothers came and mothers went. Babies came and babies went. Tests were taken—laughing, crying, goo-gooing, and driveling. Then a choice was made.

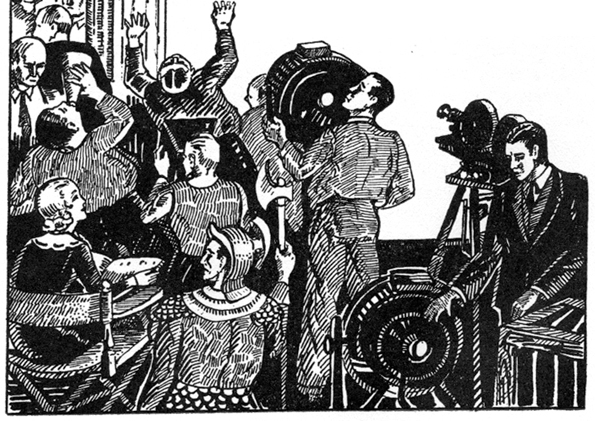

The picture was to be spectacular—“colossal,” to use the producer’s enthusiastic expression, born of hope.

“Yes,” all employees agreed, and whispered, “The picture of the year,” to any listener.

Violent activity began. Romans hurried about the lot in togas, in armor, and in the near-nude painted a swarthy brown. Greeks carried huge spears. Fiery steeds hauled gilded chariots. Wise men stroked long, false beards, assimilating their characters after true information from the research department.

Enthusiasm reigned. The studio became an ant hill of activity.

Cameras finally began to grind. Battle scenes were shot and

|

|

Read “Double’s Cross” >