The days remaining in our April fundraising drive are dwindling down. If you’re even an occasional listener, help us pay the annual bill to our streaming provider. $40 covers an entire month, but literally any amount is appreciated. If you like our toe-tapping tunes, don’t take them for granted. Let us hear from you by clicking the link below and sending us a little love via Paypal.

Charles Ray was a popular juvenile star in the 1910s and ’20s, but by the ’30s, his career was on the rocks, and he turned to writing. Here’s another in a series of offerings from his book, Hollywood Shorts, a collection of short stories set in Tinseltown.

Charles Ray was a popular juvenile star in the 1910s and ’20s, but by the ’30s, his career was on the rocks, and he turned to writing. Here’s another in a series of offerings from his book, Hollywood Shorts, a collection of short stories set in Tinseltown.

“How does Elbert do it?” was often asked by the skeptical. “He only does small bits and doesn’t work much. Where does he get the money to hang on in pictures?”

“He’s swell,” was invariably the answer. “He’s probably got a dinky income, and has a crazy yen for acting.”

Though Elbert hated himself for it, he carried a profound secret. It was a case of life or death to him; so he didn’t know what to do about it.

Wherever he went, he always arrived with a present of some sort for his hostess. But sometime during the evening, as opportunity afforded, he would purloin some object of value from her house, converting it to cash by mail in another city.

At last a night of nights came to lift Elbert’s weary soul out of the mediocrity of time. A picture was to be previewed in which he had an excellent part. Betty Harlow was giving a large party in his honor.

All during the filming of the picture, everyone had indulged in thrusting goodnatured jests in his direction. But each inwardly felt that the jinx had been lifted, that in the future something might be expected from Elbert in the nature of fine screen portrayals.

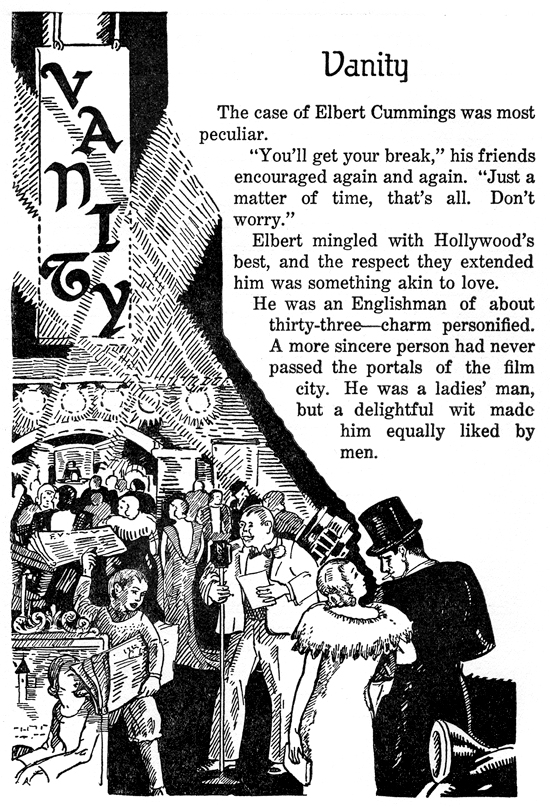

At Betty Harlow’s there was the buz-buz of sincere conversation, the good feeling which accompanies true regard. Quite the center of things, Elbert was happy. His hostess was happy too, for he had showered her with flowers by messenger, and arrived with his opera hat housing a corsage of orchids which he extracted as a magician does his rabbits.

“Wear them for me, Betty,” he pleaded charmingly. “This is my coming out. So you must be my motion-picture godmother and launch your filleul properly.”

Laughter rang against the walls, over cocktails, over a gorgeous dinner table, over coffee in the drawing room; then suddenly faded entirely out.

Elbert’s presents were forgotten. Betty’s mind became filled with vexation over a mislaid vanity case, a wonderful example of the jeweler’s craft. Its platinum surface was broken with square-cut diamonds which reflected the blood of a gorgeous ruby.

“It’s got to be found—or else!” Betty demanded of her maid in tones for the whole house to hear.

A jolly atmosphere was clouded with tragedy. Guests stood waiting to depart, embarrassed, fumbling with hats and capes in an effort to keep occupied. Eyes met eyes with wondering expressions.

“The dirty thief!” mumbled by Betty, had dampened congenial conversation.

As Betty paired her guests, sending them to their retrospective cars, everyone spoke in whispers. Then gay-colored motors sped to the preview with funereal-looking passengers.

Arc lights, maneuvered by electricians, splashed the theater building with colorful and criss-cross patterns of brilliance. Long ropes formed a lane from the curb to the entrance, through which celebrities passed a gaping populace on a soft runner of carpet. As a jolly master of ceremonies announced each name from a loud speaker, hearty applause proclaimed the popularity of a king or queen of the House of the Silver Screen.

A Hollywood world premiere was in progress.

The low cadence of conversation filled the theater before the overture; but Betty Harlow’s party of twenty-two arranged itself without smiles or repartie from the hostess. The lost vanity had cast an ominous spell which compelled everyone to sit like a mourner. Only Elbert Cummings smiled.

Whether his smile was real or not, only the gods knew. He was meditating, not a little, on why such a wealthy person as Betty would spoil her own reputation, and an evening for such a distinguished party, over a mislaid vanity. Then his meditation shifted from affluent to poverty-stricken humans and his own penny existence. Once again he hated the day that he first conceived the idea of purloining. Of course, he reasoned sincerely, if this picture should make a change in the course of his career, he might forgive himself for the past, and forget—

A blare of trumpets vibrated life into his soul.

The orchestra struck up an inspiring march. The leaden party responded into a union of interest. As the picture faded in, the lost vanity faded out of their minds.

Heavy applause rang against the theater walls. As each star and featured player received the plaudits from friends and admirers, Elbert sat motionless, hoping.

Happily awaiting his first appearance in the picture, he speculated on just how much applause he might receive. Friends and acquaintances had boosted and encouraged him for so long that now it was all to be as much a part of their success as his. Many had voiced it in so many words.

It suddenly occurred to Elbert that he might be called upon for a speech. Rapidly his mind started formulating a short message of thanks for friendly encouragement which had evidenced more confidence than he had in himself.

To an enthusiastic, brilliant audience of first-nighters, the picture gradually unreeled its action and sound with colorful elegance, assuring its future success.

Elbert grew nervous with the moments. He shifted about, squirmed, and grew pale. As each foot of film reflected the countenance of other performers, his heart shrank and a feeling of nausea left him weak.

He wasn’t wondering now how good he might be in his part, nor how he would be acclaimed. He was wondering how deep in the picture he was to make his first appearance, and how much footage he might possess after he did make an entrance.

Reel after reel passed, and sequence after sequence blended into one another until at last the cold, bitter truth hit at his heart like a spear with death-like poison on its end. He became fully cognizant that he was not to have a good part, a nice part, or even a small part. He was not to be seen at all. His role had been completely eliminated from the story.

Humiliated beyond endurance, his heart cried for a quick departure. There could be no possible way in which to meet the glances of pity for him when the lights came up full again. No amount of effort could erase the expression that would be imbedded in his face. With a low mumbled apology to the lady on his right, he pulled himself together and slunk unsteadily up the dark aisle toward the foyer.

The fresh air of the outer lobby had a reviving effect, but bystanders stared so strangely that he hurried on like a wounded animal.

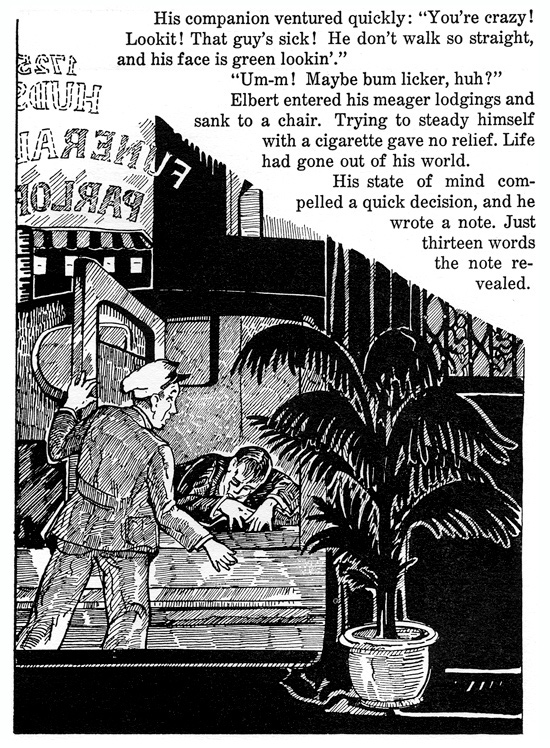

“There goes Elbert Cummin’s,” a newsboy stammered. “Musta been a bum pitcher, he’s walkin’ out on it.”

real thief may never be known.”

Wearily he shuffled through the night to Betty Harlow’s home and laid a package at her door. After ringing the bell, he darted behind some shrubbery in the garden.

Like one who has untangled the last thread of a complicated knot, he experienced a warm, grateful feeling when he saw the maid pick up the package and close the door.

At the corner drug store, Elbert thumbed a telephone book for an address which he wrote on his personal card. When he emerged to the street, he handed the card to a taxi driver as if it were too great an effort to speak any more.

Some minutes later, the taxi driver pulled at his brakes, lighted the dome light, and announced:

“Number 1725, sir.”

When there was no response, the driver alighted and opened the door. A quick flash of understanding surged through him when he found Elbert Cummings crumpled in a heap upon the car floor. With a shudder, he turned toward number 1725 and saw purple and gray drapes framing a large window with a single palm plant. By the palm plant, a ghost-green electric sign spelled: HUDSON FUNERAL PARLORS.

< Read "The Studio Cat" | Read “Sour Puss” >