In Chapter 12 of his 1930 memoir, Vagabond Dreams Come True, Rudy Vallée finally gets around to providing some typical memoir material, sharing tales of his boyhood in Westbrook, Maine, and offering accounts of his experiences traveling west to Hollywood to make his first picture, The Vagabond Lover (1929).

From Westbrook to Hollywood

IN EVERY interview that I have ever given I have been careful to state that my birthplace was a small town in Vermont called Island Pond. Most peculiarly, however, the interviewers have seen fit for some reason to omit this fact and to refer to me as a Maine boy. Probably this is due to the fact that i spent only two years of my life in Vermont. Although I grew up in Maine, I am very proud of my Green Mountain birthright, and the vacations that I have spent in Island Pond were some of the most wonderful days of my life.

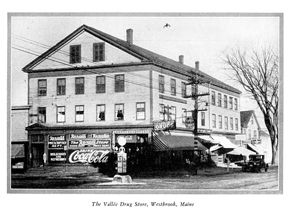

However, it was during my boyhood in Westbrook, Maine, that I first began to dream of the theatre. I must have inherited a love for all things theatrical from my father who, though a druggist all his life, had been associated with several theatres in various small business ways. Anyway it was always in the back of my head, and even when I was in the early grades of grammar school I used to climb up by the door of the motion picture booth and peek in to watch the film with fascinated eyes as it went past the aperture plate, with the bright light from the arc lamp shining on it; and the hum of the machine as the operator cranked it by hand, and the smell of film and film cement meant as much to me as the picture itself.

However, it was during my boyhood in Westbrook, Maine, that I first began to dream of the theatre. I must have inherited a love for all things theatrical from my father who, though a druggist all his life, had been associated with several theatres in various small business ways. Anyway it was always in the back of my head, and even when I was in the early grades of grammar school I used to climb up by the door of the motion picture booth and peek in to watch the film with fascinated eyes as it went past the aperture plate, with the bright light from the arc lamp shining on it; and the hum of the machine as the operator cranked it by hand, and the smell of film and film cement meant as much to me as the picture itself.My idea of perfect happiness in life was to be the manager of a theatre, who not only selected the films to be shown, but could sit in the theatre all day and watch them.

My last years of grammar school I knew I would have to help father in the drug store. I had grown into long pants and I began my first work in the drug store. Being rather dexterous with my hands and quick of mind I proved to be one of father’s best clerks, but I never liked the work. It was that I actually disliked manual labor; I never minded chopping eighteen pails of ice every day and bringing them upstairs and then packing the ice around the things that had to be kept cold (this was in the days before they had iceless refrigeration) nor did I mind opening the boxes containing countless small boxes and bottles which had to be put away in a thousand and one places in the store.

I enjoyed making the syrups, and usually gorged myself on them as I drew them from the large bottles in which they came—I was particularly fond of chocolate syrup and usually became sick from overindulgence.

But it was the fact that there was little of romance in waiting on customers who were slow in making up their minds, and who were cross and disagreeable at times; it made me miserable. Then again there was nothing fixed about the hours, we worked from early morning until late at night. Many a time father and I were just about to close the store when a street car would stop in front of our place filled with people coming back from a near-by dance hall and rust theatre, and again we would put on the lights, open the doors, and in a breathless rush serve forty and fifty people at the soda-fountain.

I had to rush out on cold days and pump gasoline, as we were one of the first drug stores to have a gasoline filling station. The only happiness I knew in the store was when father took on the sale of Victor photograph records and I had a chance to give demonstrations to possible purchasers of these records. After I had played them twice over, I usually knew all the good and bad features of the records and could invariably whistle and hum along with them. I knew the selling points of each and very rarely failed to sell a record when i attempted to do so. The thing lasted all too short a time but its effect upon me was profound and tremendous.

A small event of great future import took place a the beginning of school vacation when a disagreement with the head clerk affected me so that I walked out of the store and went out swimming with the boys.

We had one small movie theatre in the town, the Star Theatre, which was my idea of the last word in motion picture theatres. I heard that a boy who worked as assistant operator was leaving his job and that the manager needed someone to take his place.

I must have loved things theatrical when I could get there early in the morning, sweep the entire theatre out, downstairs and balcony, with an ordinary broom, and between the two shows, sweep the places where thoughtless people had thrown their peanut shells, sweep out the projection booth, clean and oil both machines, change the carbons in the lamp house, rewind the films, help put out the posters, take care of the furnace, polish the brass around the billboard sheets in front, and even take tickets until the show began; but I got my reward!

I was given the poorer of the two projection machines to operate, and I will never forget the tremendous thrill when the chief operator roughly called to me, gave the crank a great twist, and left me, all a-tremble, to catch it before it stopped and to continue to project the film. I got one of the greatest thrills of my life as I looked out through the hole in the booth to see the personages on the screen who were all brought to life by the magic crank which I held in my hand.

But after standing there hours and hours in the unbearable heat of the booth, cranking for fifteen minutes at a time, always watching to see that the light showed properly on the film, I was somewhat less excited; still I always loved it.

The show changed three times weekly, and the three nights before the changes, the two-reel comedy had to be carried to Portland, six miles away, to be shipped to another theatre on the same chain. I tied the film to the carrier back of my bicycle and bicycled to Portland, left the film at the station and then wearily pedaled home. The point was that I saved the carfare; I felt very happy in the thought that I had earned the extra twenty cents.

For all my labors in the theatre six days a week (thank heaven there were no Sunday shows in Maine!) I received the magnificent sum of seven dollars, but I was prouder and happier when this pay envelope came to me than I had ever before been in my life, and although my father tried to prevent me from working there, he saw that I was determined and permitted me to continue at the theatre instead of working in the store.

I continued doing this for two years before i went to Maine’s largest theatre, the Strand in Portland. After having served such an apprenticeship in pictures at so little money, it is not difficult to imagine the elation I felt when I left for Hollywood with my boys, in a special car all our own, to be a star in my first picture at a salary of $11,000 a week.

The first night I went to sleep in my berth on the Pullman was perhaps the happiest of my life. I went off to sleep thinking that I was actually going to accomplish the thing that I had often dropped off to sleep dreaming about when just a boy.

The question “How did you enjoy making pictures?” to me is a silly one, because there can be no boy who has not at one time or another wanted to take part in a dramatic playlet that brings a beautiful woman into your arms, takes you with her through trials and misfortunes and finally brings the happy ending. It is fun enough to do this anyway, but to be paid for the effort is certainly doubling the pleasure of the task.

To some of the stars in Hollywood, picture making is extremely arduous, and of course it really is, but to my boys and me it was comparatively easy work after the very strenuous program that had been ours for months. Picture work seemed child’s play after week after week of four and five shows a day, night club at night until three, early morning recordings, rehearsals, broadcasts, personal appearances, and what not.

True, picture making is a task, because the rehearsals and the final shooting of the picture are much more difficult and nerve-wracking than were the rehearsals for those high school or community plays that most of us did not so long ago. And now, with the coming o sound to pictures, much more is demanded of the actor not only in voice but in talent and initiative during the filming of the scenes, since the talkies have shorn the director of his chance to direct the final shooting.

The talkies have brought doom and despair to many formerly successful stars, but hope and success to others who otherwise would never have succeeded. Such, I suppose, is my case, but since the technique of making sound pictures is almost identical with the principles of broadcasting, I began my career in pictures at the peak—as a star, thus eliminating all those other preliminary steps of extra or featured player.

In the choice of a story it was necessary to have one that would bring the seven boys into the picture and give them a logical reason for being there, but yet we wanted to avoid the hackneyed night club, back stage and college campus ideas. Nearly all of our sound pictures today s deal with one of those three themes in order to bring music into the plot. Therefore, barred from the dramatic complications of these three angles we had to choose a very simple story.

My part, as I conceived it, was that of a shy, embarrassed boy who was in a group of orchestra boys who considered themselves superior to him; a boy whose high idealistic principles caused him to be conscience-stricken throughout the entire picture due to the deception which he was practicing. Furthermore, being in a daze of puppy-love from the moment I met the heroine of the story, I was continually in hot water. There was little opportunity on my part for very much animation or life, and hardly a chance to smile. What we commonly term “personality” is made up of just those things. The part was practically “personality-less,” but it gave me a real excuse for everything I did, especially the singing of my songs, which after all, was perhaps the most important thing in the making of the picture.

Before we left for the Coast I listened daily to eight or ten songs, and finally from a group of nearly two hundred I selected the four songs which are in the picture. It was necessary that I do this in my dressing-room at the Brooklyn Paramount Theatre at which we were playing. It was in the hot summer time and I came of the stage very tired from the heat and stage work, but between every show it was necessary that hear these songs over and over again in order to make up my mind.

I do not believe absolutely in first reactions; rather do I believe that it is necessary to hear a melody several times in order to pass judgment, and it is really best to hear the melody at intervals of several days, and then if a tune does not come back and haunt the mind it usually has little merit. I rated the songs like themes in school, A, B plus, B, and so forth.

The story was still vague when we left for the Coast, so I carried eight songs marked A with us, hoping that at least four would fit in the picture. Whatever their opinion of the picture as a whole, the critics have usually complimented us on the sporting of the songs and their rendition, and the fact that all four are selling excellently, and one, “A Little Kiss Each Morning,” is the outstanding hit today, makes me feel very happy. One of the songs, “If You Were The Only Girl In The World” is a tune about twelve years old, but had failed so miserably as a fox trot that its publishers had soured on it. I tried to convince them that it was a hit song if played as a slow waltz. This idea, too, has proved itself since the picture came out.

Our trip came as a wonderful relaxation, and to some of the boys it was a belated honeymoon, as all of them brought their wives. The bass player and I are the only single ones. I took my best sweetheart, my dear mother, and my father. Feeling that he had worked long enough in the drug store, having been behind the counter twelve and fourteen hours a day for twenty years, I wrote my father to sell the store and come West with us on this glorious trip.

We have relatives in Pasadena, and father and mother were very happy visiting, watching us make the picture and attending the social functions with me which Hollywood and Los Angeles showered upon us.

From the time we let the Pennsylvania station, with the goodbyes of fans, newspaper men, publishers and others ringing in our ears, it was one constant reception in every town of any size stopped at. They even woke me in the middle of the night to pose for the newspaper cameramen of the various towns we went through, while a radio delegation or a representative of the theatres that sponsored our picture greeted me.

At Chicago I was tendered a delightful breakfast with the press in attendance.

But the biggest surprise of all came as we neared Los Angeles when, a few miles out, fifty representatives of the press and screen magazines climbed aboard the train. After dinner and refreshments I became the target for their interviews. But I had become accustomed to the questions and it was a pleasure to answer them.

Then we drew in to Los Angeles to find a tremendous delegation waiting for us—movie cameramen with bright lights, fifteen girls from the studio and a big crowd of radio fans and curious onlookers. The Sheriff of Los Angeles was also there with letters of welcome from both the Governor of California and the Mayor of Los Angeles.

The studio girls, who form the dancing chorus of such productions of “Rio Rita,” surrounded me, making a general wreck of me as they pushed and pulled me about among them. Then I was presented with a big saxophone of wood and a large gold key.

After a formal ceremony, pictures were taken of me with my parents, and of the Sheriff and myself, and microphone recordings of our response to the greetings were made. We were then escorted to a Rolls-Royce and, followed by a long line of cars carrying my boys and various officials, started for Hollywood, the sirens of four motor cycle cops securing the right-of-way for our procession the entire distance. This last gave my mother the great thrill she ever had, and I can still hear her, hysterically half-laughing, half-crying. It was really wonderful.

At the Hotel Roosevelt in Hollywood we were greeted by Irving Aaronson and his Commandeers, playing my own “I’m Just A Vagabond Lover,” and our welcome was complete.

As the last part of the trip across had been almost unbearable and we were all feeling very tired, we retired at once.

My faith in the production head and scenario writer was justified, as the story of the picture was simple enough and yet of sufficient interest to make it a fine vehicle for our work.

I was most fortunate in having Marshall Neilan as director of my first motion picture; he is not alone a great director, but a very human individual with a great understanding of my songs and a keen with a great understanding of my songs and a keen insight into the art of recording them, being a fine musician himself. His crew of light experts (who can make or mar the features of the players) the sound recorders, the cameramen, the make-up man, who after some study finally evolved my best make-up, all helped to solve the difficulties of picture making that I had dreaded most of all.

Such notables as Marie Dressler, Sally Blane, Charles Sellon and others of wide and varied experience, who were in the cast, did much toward making the picture a success. In fact the honors are entirely Marie Dressler’s. Everything in and about the studio was perfect, everyone gave his co-operation, we did our best, and if it seems not to please our great film public it will be just that it was not to be.

We were wonderfully received in Hollywood, being the recipients of receptions at Breakfast Club, Masquers, Montmartre, and many other places, but our greatest reception was in the Blossom Room of the Roosevelt Hotel. It was a Tuesday evening, and the room was filled to overflowing with the greatest collection of notables and stars of the movie world I have ever seen under one roof.

Many of these were famous when I used to crank films in the booth of the little Star Theatre, and the feeling that went over me as I saw them there honoring me with their presence made me very happy indeed.

On the eve of our departure for New York I was happy to give a banquet in the Cocoanut Grove of the Ambassador, and everyone who had participated in the making of our picture, from the greatest to the humblest “grip” who carried the lamps and helped move everything, was there. It was a wonderful evening; Ted Lewis was playing there, everybody was happy and the place was jammed. Of course there were speeches, and we left with a wonderful feeling in our hearts for California and Hollywood.

With faces turned to New York, we set out for our routine of continuous work again; but all the time I was on the Coast I received pleading letters from those who missed our radio programs, those who were confined to sick-rooms and who really looked for our return with longing, I felt that I owed an allegiance to them and looked forward to playing for them on the air once again.

For a time we feared that our picture had been destroyed in the vaults of the company where they made the reproductions of the original. But it was saved and only small parts destroyed. At any rate, I will never forget its première and the wonderful thrill of pleasure that I received when after what seemed an interminable burst of applause I stepped out on the stage to say a few words and express my appreciation to RKO and everyone who had helped us to make it.

Perhaps the greatest honor conferred upon me was the wonderful way in which my home town turned en masse to see the picture. The Mayor, Kiwanians, Rotarians and American Legion all united in declaring the day on which the picture was first shown a municipal holiday. A long procession of automobiles and street cars went from Westbrook to Portland, over the same route that I used to bicycle over with the two-reel comedy film, to do homage to a local son in his first talking picture.

In most places the picture was well received. It was not intended to be elaborate, but a simple and logical entrance for me into the movies. In my second picture I hope to show that I am capable of the things that have come to be expected of motion picture stars.