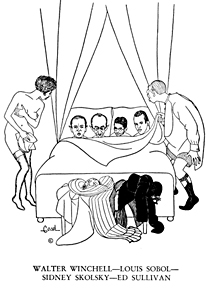

In Chapter 9 of In Your Hat, the 1933 tell-all memoir by Hat Check Girl to the Stars Renee Carroll, she offers recollections of more celebrities than we could possibly list here. Many of the names are still familiar; others all but forgotten. A few we couldn’t even track down via the internet, and heaven knows we tried.

EVEN Fred Keating, the magician, once forgot where he put his hat check!

But hat check girls, even red-haired ones, have memories, so sometimes when business at my window is slack, I sit and think of the million and one things that have happened between the celebrity-laden walls of Sardi’s. Incidents, names, personalities galore, and sometimes just a casual word will start my train of thought along almost forgotten tracks. Would you like to lift the lid of the Carroll cranium and see what’s going on inside?

Here comes George Jean Nathan, world’s best critic by his own admission. I’ll never forget the day I bawled him out because he insisted on having his hat set apart from the others—and how embarrassed he was. I never suspected anyone could embarrass him . . . telling Warner Baxter that he was my favorite movie star, only to be overheard by Richard Dix to whom I had dished out the same line only two days before . . . the day Helen Menken, reddest of the red-heads, gave us a big surprise by changing to the color gentlemen are supposed to prefer . . . Incidentally, she never takes her gloves off when she eats!

And here is Robert Garland, who pilots (or piles-it) the dramatic column in the World-Telly, and is a regular customer as a certain blind spot in the roaring Fifties (they’re roaring further uptown now). He’d been a regular patient at the drink infirmary for more than a year when one night he showed at the barred door and knocked the magic knock. A weary, unshaved faced appeared in the aperture.

And here is Robert Garland, who pilots (or piles-it) the dramatic column in the World-Telly, and is a regular customer as a certain blind spot in the roaring Fifties (they’re roaring further uptown now). He’d been a regular patient at the drink infirmary for more than a year when one night he showed at the barred door and knocked the magic knock. A weary, unshaved faced appeared in the aperture.

“Pliss?”

“Hello, Tony, I wanna come in.”

“Who are you?” the face inquired.

Infuriated because he had spent his good shekels for so many nights and still remained a dim bulb in the big sign, he shouted back the first thing that came to his mind—a catchline from a New Yorker cartoon.

“You must remember me,” yelled Garland, “I’m the guy who punched my wife in the nose here last night.”

And he was ushered in with any more undue ceremony!

Read More »