The musical was a popular genre in the very early days of talkies, but the moviegoing public quickly (if briefly) lost interest in singing pictures.

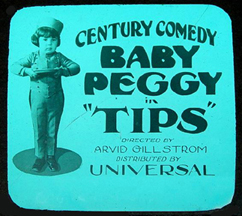

One movie that fell victim to that disinterest was King of Jazz (1930), a lavish musical-comedy revue that featured Paul Whiteman‘s orchestra delivering an assortment of musical numbers with comedic sketches interspersed throughout.

King of Jazz, made for Universal Pictures, was filmed entirely in an early, two-color version of Technicolor and featured actors and performers such as the Rhythm Boys (Bing Crosby, Al Rinker and Harry Barris, don’t you know), John Boles, Laura La Plante, Slim Summerville, Walter Brennan, jazz legends Joe Venuti and Eddie Lang, and the Russell Markert Dancers (who would soon become the Radio City Music Hall Rockettes).

King of Jazz was not a money-maker, and a revamped version released a few years later did no better, so it might well have fallen into obscurity and been forgotten, but over the decades, interest in the film increased. In 2013, the film was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry, and in 2018, a spectacular restoration of the film was screened in a few locations across the country and around the world.

We were present for the restoration’s premiere in New York City, and it proved to be a terribly exciting event. The buzz in the theatre was palpable and the film, which had been beautifully restored, received cheers from the packed house throughout the screening.

We’re pleased to share the exciting news that Turner Classic Movies is airing this acclaimed restoration on Monday, March 4, at 8 p.m. ET. If you listen to Cladrite Radio with any regularity, this one’s right up your alley. We’re calling it a don’t-miss.

To give you an idea what to expect, here’s a clip from the film of a performance of George Gershwin‘s Rhapsody in Blue.