Did you ever wish you could be there for the first performance of an iconic work—say, the debut of George Gershwin‘s “Rhapsody in Blue” as performed by Paul Whiteman‘s orchestra on February 12, 1924, at NYC’s Aeolian Hall on West 43rd Street?

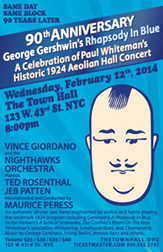

Did you ever wish you could be there for the first performance of an iconic work—say, the debut of George Gershwin‘s “Rhapsody in Blue” as performed by Paul Whiteman‘s orchestra on February 12, 1924, at NYC’s Aeolian Hall on West 43rd Street?

Well, we don’t have a time machine to lend you, but here’s the next best thing. Vince Giordano and the Nighthawks, masters of the sounds of the 1920s and ’30s, are recreating that historic concert in collaboration with conductor Maurice Peress and pianists Ted Rosenthal and Jeb Patten.

Town Hall, which sits on that selfsame block of 43rd Street, is hosting this historic event on February 12th—ninety years to the night after the original concert.

It’s hard to imagine an event that might be considered more of a “don’t-miss.” Get your tickets now!