“It’ll be a great place if they ever finish it.”

“It’ll be a great place if they ever finish it.”

—O. Henry, on New York City

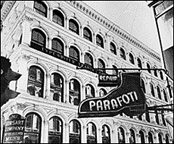

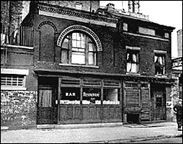

In 1929, photographer Berenice Abbott returned to the United States from Paris, where she’d spent eight years, first serving as Man Ray‘s photographic assistant and later establishing her own reputation as a portrait photographer.

She intended to spend only a few weeks in the U.S. but was so taken by the transformation New York City was undergoing, with dozens of tenements and other older buildings being razed to make way for the new skyscrapers that were cropping up all over the Big Apple, that she decided to remain in New York.

She supported herself for some years with portraiture, but she dreamed of documenting the modernization of New York in much the same manner Eugène Atget, a documentary photographer whose work Abbott had championed during her years in Paris, had captured a changing Paris decades earlier.

In 1935, the WPA supplied Abbott with money, a photographic assistant, and a team of nine research assistants. She spent the next four years documenting Depression-era New York.

These resulting images are remarkable in their ability to conjure an earlier time in the life of this most dynamic of cities, for showing modern-day New Yorkers and the city’s visitors just how much the city has changed in the ensuing 75 years. New York City not only doesn’t sleep, it refuses to sit still.

A few years ago, we did a bit of strictly amateur “after” photography to contrast with Abbott’s “before” shots, even as her photographs were an updating of what had come before. Stroll with us through these neighborhoods, all south of 23rd Street; treasure what remains from Abbott’s time and imagine what is still to come.

To view the then-and-now images side by side, just click the thumbnails below.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If you’re intrigued by the above, you’ll find much, much more of Berenice Abbott’s work here.