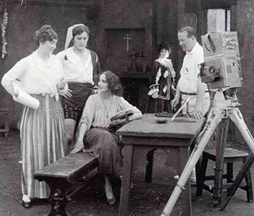

Jimmy Starr began his career in Hollywood in the 1920s, writing the intertitles for silent shorts for producers such as Mack Sennett, the Christie Film Company, and Educational Films Corporation, among others. He also toiled as a gossip and film columnist for the Los Angeles Record in the 1920s and from 1930-1962 for the L.A. Herald-Express.

Starr was also a published author. In the 1940s, he penned a trio of mystery novels, the best known of which, The Corpse Came C.O.D., was made into a movie.

In 1926, Starr authored 365 Nights in Hollywood, a collection of short stories about Hollywood. It was published in a limited edition of 1000, each one signed and numbered by the author, by the David Graham Fischer Corporation, which seems to have been a very small (possibly even a vanity) press.

Here’s “Kalsomine Kitty of the Kleigs” from that 1926 collection.

KALSOMINE KITTY OF THE KLEIGS

When they made Tommy Green a director the sun beamed a satisfied smile on the big white stages. The birds which infested the trees along the avenue running through the studio, talked about it in chirps.

When they made Tommy Green a director the sun beamed a satisfied smile on the big white stages. The birds which infested the trees along the avenue running through the studio, talked about it in chirps.The white-haired gateman stepped from his self-made pinnacle of pride and told the extras in the waiting room.

The noon whistle seemed to scream its congratulations at twelve o’clock.

They had finally made Tommy Green a director.

It was discussed over the lunch counters, in the studio cafeteria and over the white tablecloths at Mother’s Inn.

Everyone was talking about it.

Everyone was glad—glad for Tommy.

After eight years he had gained the position he had always dreamed of and worked for. Yes, it had been worth while. It seemed a long time, and Tommy had struggled hard. But it had not been in vain after all.

Eight years ago he walked into the studio and asked for a job. Lady Luck had presented him with a prop assistant’s broom and apron and told him to work eight hours a day for twenty-five dollars a week.

Today his salary began with fifteen hundred dollars a week. His contract stated this for one year and an option on five years.

Tommy sat gazing out of his new office window into the studio street. Electricians with leather vests scuffed by. Office boys with Oxford-bag trousers and patent leather shoes strolled slowly, carrying notes to directors.

Girls flickered past in fashion’s latest, carrying manila envelopes with photographs. Some had make-up kits.

Old men with unpressed clothes and Merry Christmas whiskers hobbled by. Young men with highly polished hair and trick suits wandered up and down the street.

Trucks with props whizzed back and forth.

Actors with pink make-up and funny looking clothes hurried from stage to stage. An orchestra was playing “Hearts and Flowers” on Stage One.

On Stage Two a snow scene was being put on. The cameraman cranked away in his shirt sleeves while an electric fan played upon him.

The girl in the salt snow shivered and thought of an ice cream soda.

Tommy looked at his stenographer who wore massive earrings. She was typing out the working synopsis of his first story.