! ! ! * * * @ @ @ ! ! ! * * * *

Tag: Joan Bennett

Forget the forest; it’s all about the trees

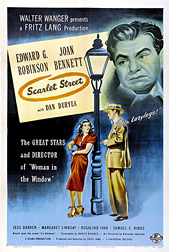

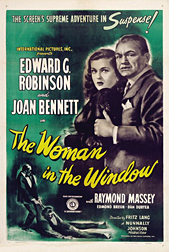

We took in a Fritz Lang double feature yesterday afternoon at Film Forum: Scarlet Street (1945) and The Woman in the Window (1944).

We took in a Fritz Lang double feature yesterday afternoon at Film Forum: Scarlet Street (1945) and The Woman in the Window (1944).

As one might expect from Lang, they were both solid pictures, both in the noir vein and both starring Joan Bennett, Edward G. Robinson, and Dan Duryea.

And yet, in a way, the two pictures are reverse images of one another. Scarlet Street is oddly whimsical throughout; the circumstances—a young woman and her shiftless boyfriend work to take a bank cashier and would-be artist for all he’s worth (which is far less than they imagine it is)—are typical of film noir, but the tone of the performances isn’t. The packed house at Film Forum tittered and chuckled throughout, and we couldn’t help wondering if that was what the filmmakers were aiming for. But they weren’t laughing at any perceived ineptitude; the laughs did seem intended.

But the ending of the picture is as bleak as any classic noir. It was a bit jarring.

The Woman in the Window, on the other hand, takes a more traditional approach to its noir tale of a middle-aged professor and a glamour gal who unintentionally commit murder and spend the rest of the picture trying to avoid having the deed be traced to them. It’s cleverly done and witty, but not nearly as lighthearted as Scarlet Street.

The Woman in the Window, on the other hand, takes a more traditional approach to its noir tale of a middle-aged professor and a glamour gal who unintentionally commit murder and spend the rest of the picture trying to avoid having the deed be traced to them. It’s cleverly done and witty, but not nearly as lighthearted as Scarlet Street.

But the twist ending (don’t worry, we won’t spoil it) takes the picture in a different direction entirely.

Both films are available on DVD and are well worth watching.

As we always do when we’re viewing a pre-1960 picture, we found ourselves watching for small background details, in the decor of the apartments in which the stories took place, the design of the clothing worn by the actors, the terms, slang and otherwise, used in the dialogue. It’s a habit we picked up long ago, as our interest in life as it once lived grew ever more avid.

Our visual scouring when watching an old movie goes even so far as to take note of the titles on a book shelf, if we find a shot that pulls in close enough for us to make them out. In The Woman in the Window, there’s a scene that finds Duryea, playing a lowlife blackmailer (is there any other kind?), is searching for some hidden dough in Bennett’s apartment, and in conducting the search, he pulls down a handful of books from a shelf on the wall.

He leaves a few books behind on that shelf, and in doing so, the title of one of them is made clearly visible (it’s visible on the big screen, at least, which is just one more argument for seeing classic movies in a theatre whenever possible). We made a mental note of the title, for no good reason whatsoever beyond curiosity, with the intention of doing a little digging when we got home.

The book was entitled “30 Clocks Strike the Hour.” We were left wondering whether it was an actual book or a dummy one mocked up by the prop department at MGM. We were inclined toward the latter possibility.

Well, as it turns out, we were wrong. The book is a collection of short stories by Vita Sackville-West, a prominent and prolific English author and poet who penned more than 10 books of poetry, at least 17 novels and short-story collections, and a handful of biographies. Sackville-West is also remembered for the lengthy string of affairs she conducted with a number of prominent women, including one with Virginia Woolf that is said to have inspired the novel Orlando (Ms Sackville-West and her husband, writer and politician Harold George Nicolson, practiced open marriage).

Well, as it turns out, we were wrong. The book is a collection of short stories by Vita Sackville-West, a prominent and prolific English author and poet who penned more than 10 books of poetry, at least 17 novels and short-story collections, and a handful of biographies. Sackville-West is also remembered for the lengthy string of affairs she conducted with a number of prominent women, including one with Virginia Woolf that is said to have inspired the novel Orlando (Ms Sackville-West and her husband, writer and politician Harold George Nicolson, practiced open marriage).

So it likely says more about us than it does of Ms. Sackville-West that not only didn’t we recognize the title of the book, we were previously altogether unaware of her life and career.

But that’s okay. We know about her now, and who knows? We might even pick up a copy of Thirty Clocks Strike the Hour one of these days. After all, if it was good enough for Alice Reed, Bennett’s character in the picture, it is very likely good enough for us.

Having authored a book of our own a few years back, we have to admit we’d get a kick out of seeing our humble little hardback sitting on a shelf during a given scene in a movie, especially a film that eventually comes to be viewed as a classic and is still drawing sold-out houses 66 years after its debut, as is The Woman in the Window.

We like to imagine some guy or gal, ca. 2077, with an interest in the cinema of the early 21st century and an eye for detail, undertaking a search via the web (or whatever has replaced it by then) to find out if our book (and, by extension, we) really existed.

It’s remarkable, really, what one can discover by looking beyond the cinematic forest at the tiniest trees.