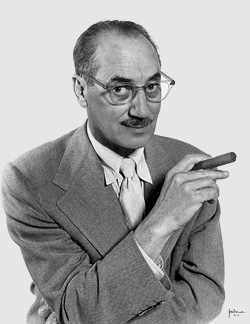

A 23-second fragment of the lost silent Marx Brothers film HUMOR RISK, self-financed by the team in 1921. The film was discovered earlier this month and is now in the hands of a private archive.

Previously thought destroyed in its entirety, this small portion of the film was found in the garage of the former Great Neck, NY, estate of Groucho Marx.