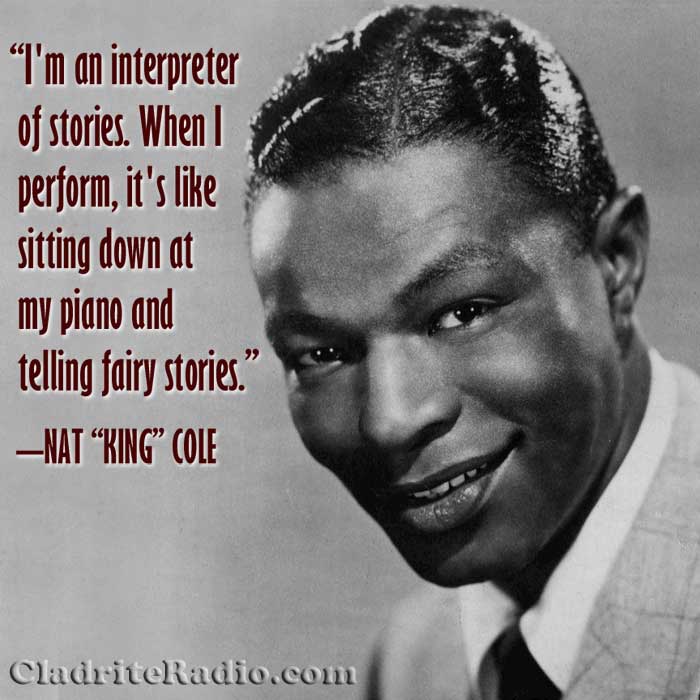

Today Nat ‘King’ Cole, born Nathaniel Adams Coles 97 years ago today in Montgomery, Alabama, is widely associated with his pop hits of the 1950s and ’60s, but his musical career extends much further back, well into the Cladrite Era. He began performing as a jazz pianist during his teen years in the mid-1930s in Chicago. His older brother, Eddie, a bass player, joined his band and the two siblings cut their first record, under Eddie’s name, in 1936. It was during this time that Nat was given his ‘King’ nickname, said to be a play on the Old King Cole nursery rhyme.

Cole hit the road as the pianist in a national tour of Eubie Blake‘s revue Shuffle Along (currently being revived on Broadway), and when the show unexpectedly closed in Los Angeles, Nat decided that Southern California suited him and remained there.

Nat ‘King’ Cole found his first success as part of a trio (though they weren’t yet the King Cole Trio, as they would come to be known, but the King Cole Swingsters). Radio was key to their rise in popularity, and they became a popular act in the Los Angeles area. Nat’s piano playing was his claim to fame, but he had started to add vocals to a number of the tunes in the trio’s repertoire.

In 1943, Nat and the trio signed with the fledging Capitol Records, and their success financed the company’s growth. To this day, the round structure that is the company’s headquarters, built in Hollywood in 1956, is referred to as “the house that Nat built.”

Cole is to this day considered one of jazz’s greatest pianists, but eventually, the popularity of his vocals overtook the acclaim his playing garnered, and his flair for crooning a pop song made him one of the most popular recording artists in the world (it’s not widely remembered today, but in the 1950s, Cole outsold Frank Sinatra by a wide margin).

Cole became so popular that on November 5, 1956, he began hosting his own television show, The Nat ‘King’ Cole Show, on NBC; he was the first African-American artist to host such a show. The show did fine in the ratings, but no sponsor for the program was ever found, a must in those days. Just over a year after it hit the airwaves, Cole pulled the plug on the show. The strain of operating a show without a sponsor’s backing was too much. After the show’s demise, Cole was quoted as having quipped, with a mix of good humor and bitterness, “Madison Avenue is afraid of the dark.”

The program’s failure proved a negligible setback, as the hits kept coming. Cole even recorded a trio of albums in Spanish (phonetic only—he didn’t hablan español). His Spanish was reportedly pretty bad, but many Spanish-speaking listeners found his clumsy efforts charming and his popularity only increased.

A favorite story of ours tells of the time that Cole moved his family into Hancock Park, a all-white Los Angeles neighborhood that was a bastion of old money (by L.A. standards, anyway). The Coles were not made to feel welcome—a burning cross was even placed on their lawn. But when members of the neighborhood property-owners association paid Cole a visit, telling him they didn’t want to see any undesirables in the neighborhood, he is said to have told them, “Neither do I. And if I see anybody undesirable coming in here, I’ll be the first to complain.”

That, our friends, was a perfect response.

We once attended an afternoon question-and-answer session with Debbie Reynolds in Las Vegas, and she mentioned Nat ‘King’ Cole as one of her favorites. We asked her if she had known him well and did she have any remembrances to share? She recalled Cole as exceedingly gentle and kind, widely respected as performer and as a man. She said he wasn’t bitter at the racial prejudice and rancor he’d encountered over the years. “It’ll pass,” she quoted him as saying. “The years will go by and it will all go away.” We wish he’d lived to see the day; we hope we will.

In 1964, Cole began to experience fatigue and back pain until finally, some time after collapsing during a show at the Sands Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, he was convinced to consult with a doctor while performing in San Francisco. He was diagnosed with lung cancer and given just a few months to live, but he kept working, recording his final sessions in early December. He died, aged 45, in Los Angeles on February 15, 1965, less than three months after his diagnosis. The severity of his condition had been largely hidden from the public, so the news of his passing proved a shock to his fans across the country and around the world.

We were not quite seven years of age when news came of Cole’s passing, and our beloved mother was one of those grieving fans. She loved Nat ‘King’ Cole’s music, and she passed that love on to us. He remains one of our favorites, and it pains us to think of all the wonderful music we’d have gotten to enjoy if he’d lived to his 70s or 80s, as other singers of the era, such as Sinatra and Tony Bennett, have done. But his musical legacy remains virtually unmatched. He excelled as a pianist and a singer, in jazz and in pop, and even managed to acquit himself reasonably well in recording a few country and R&B songs.

Thanks for all the wonderful music, Nat, and happy birthday, wherever you may be.

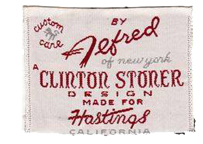

“Clinton Stoner was a freelance men’s suit and sportswear designer whose merchant clients included Macintosh Studio Clothes and Saks Fifth Avenue. In the late 1940s, he opened his own custom sportswear shop—named “Clinton Stoner”—on the east end of the Sunset Strip. Stoner’s shop was a favorite of gangster

“Clinton Stoner was a freelance men’s suit and sportswear designer whose merchant clients included Macintosh Studio Clothes and Saks Fifth Avenue. In the late 1940s, he opened his own custom sportswear shop—named “Clinton Stoner”—on the east end of the Sunset Strip. Stoner’s shop was a favorite of gangster  From its familiar opening lyrics—Chestnuts roasting on an open fire, Jack Frost nipping at your nose, yuletide carols being sung by a choir, and folks dressed up like Eskimos—The Christmas Song celebrates an idyllic holiday season, but let’s face it, for many, the holidays carry with them a tinge of melancholy—especially in difficult times like these—and Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas openly acknowledges the bluer side of the yuletide.

From its familiar opening lyrics—Chestnuts roasting on an open fire, Jack Frost nipping at your nose, yuletide carols being sung by a choir, and folks dressed up like Eskimos—The Christmas Song celebrates an idyllic holiday season, but let’s face it, for many, the holidays carry with them a tinge of melancholy—especially in difficult times like these—and Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas openly acknowledges the bluer side of the yuletide.