The late Jack LaLanne may have been the most famous and longest-tenured of celebrity fitness experts, but he wasn’t the first. Syvia Ulback, known in her heyday as both Madame Sylvia and Sylvia of Hollywood, preceded him by at least a decade.

The late Jack LaLanne may have been the most famous and longest-tenured of celebrity fitness experts, but he wasn’t the first. Syvia Ulback, known in her heyday as both Madame Sylvia and Sylvia of Hollywood, preceded him by at least a decade.

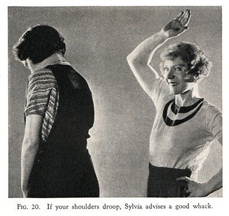

Sylvia’s beat was more beauty than fitness, but she knew full well that you can’t have the former without the latter, and she made certain her famous clients knew it, too. A masseuse by trade, Sylvia also advised her clients on proper diet and the importance of exercise.

Her client list amounted to a virtual Who’s Who of 1920s and early ’30s Hollywood, including Bebe Daniels, Ramon Navarro, Ronald Colman, Norma Shearer, Ruth Chatterton, Ann Harding, Norma Talmadge, Charles Farrell, Zasu Pitts, Constance Bennett, and Marion Davies.

Born in Norway in 1881 to artistic parents—her mother was an opera singer; her father an artist—Sylvia entered the field of nursing as a young woman. Having undergone massage training as well, she opened a studio in Bremen, Germany, when she was 18. In the early 1900s, she was wed to lumber dealer Andrew Ulback; the pair emigrated to the United States in 1921 when Andrew’s lumber business failed, settling first in New York City and Chicago before finally relocating to Hollywood in the mid-1920s.

Standing no taller than five feet, Sylvia once told The Hartford Courant that she had been inspired to pursue the reducing arts when she caught her husband eyeing a stenographer much slimmer than she. She adopted a painfully strenuous form of massage that she insisted would, when combined with proper diet and exercise, rid her clients of unwanted fat; though the claim may strike modern readers as dubious at best, the results she achieved were sufficient to ensure a quick rise for the ambitious masseuse.

Actress Marie Dressler was Sylvia’s first celebrity client, and her initial entree into that market depended entirely on garnering the approval of Dressler’s astrologer. Fortunately for Sylvia, she was given the okay.

Actress Marie Dressler was Sylvia’s first celebrity client, and her initial entree into that market depended entirely on garnering the approval of Dressler’s astrologer. Fortunately for Sylvia, she was given the okay.

Various stars came to so depend on Sylvia that they tried to monopolize her services. Mae Murray paid Sylvia to accompany her on a lengthy vaudeville tour (though Sylvia had to sue the actress for non-payment of salary upon their return to Hollywood—a suit she won), and Gloria Swanson was so impressed by Sylvia’s achievements that she arranged to have her hired by the Pathé Studio as the house masseuse at a weekly salary of $750, the rough equivalent of nearly $10,000 today. Joseph Kennedy, later patriarch of the famed Massachusetts political dynasty and then one of the studio heads at Pathé, hesitated to hire Sylvia at first, until she was able to diagnose his flat feet merely by watching him walk across a room.

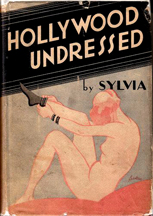

In 1931, Brentano published a best-selling volume entitled Hollywood Undressed: Observations Of Sylvia As Noted By Her Secretary. It was thought by some that the masseuse herself penned the memoir, which is filled with juicy tales of the Hollywood figures who made up Sylvia’s clientele, along with diet tips and exercise recommendations. In fact, the book was ghostwritten by screenwriter/reporter James Whittaker, first husband to actress Ina Clare.

Though—or, perhaps, because—the book broke the rules by telling tales out of school, it sold very well, but at a price. Sylvia had bitten the hand that fed her, and it hurt her standing in Hollywood. But she managed to limit the damage by adopting additional avenues of influence and income.

Though—or, perhaps, because—the book broke the rules by telling tales out of school, it sold very well, but at a price. Sylvia had bitten the hand that fed her, and it hurt her standing in Hollywood. But she managed to limit the damage by adopting additional avenues of influence and income.

Sylvia was soon writing syndicated columns on health and beauty for newspapers across the country and for Photoplay magazine; she also hosted her own nationally syndicated radio show, Madame Sylvia of Hollywood.

The radio show inspired a bit of a scandal when, in 1934, Sylvia, having aired an interview she said was with Ginger Rogers, was sued by the popular actress, who insisted that she had not taken part in any way in the broadcast. The case was settled out of court.

Sylvia also wrote three more bestselling books advising women on topics of health and beauty, this time with full author credit: No More Alibis (1934), Pull Yourself Together, Baby (1936), and Streamline Your Figure (1939).

On June 27, 1932, Sylvia, at the age of fifty, divorced Andrew Ulback. Just four days later, she married stage actor Edward Leider, eleven years her junior.

Sylvia abruptly retreated from the spotlight in 1939, enjoying a long life with Edward in relative obscurity. When she died, at age 94 in March 1975, just a month after Edward passed away, she was living in a small bungalow in Santa Monica. On her death certificate, her occupation was listed as “housewife.” Few, if any, publications noted her passing. Her influential career had been all but forgotten.

This story originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2011 issue of Zelda, the Magazine of the Vintage Nouveau. Watch this space next week for the first chapter from Sylvia Ulback’s Hollywood Undressed.