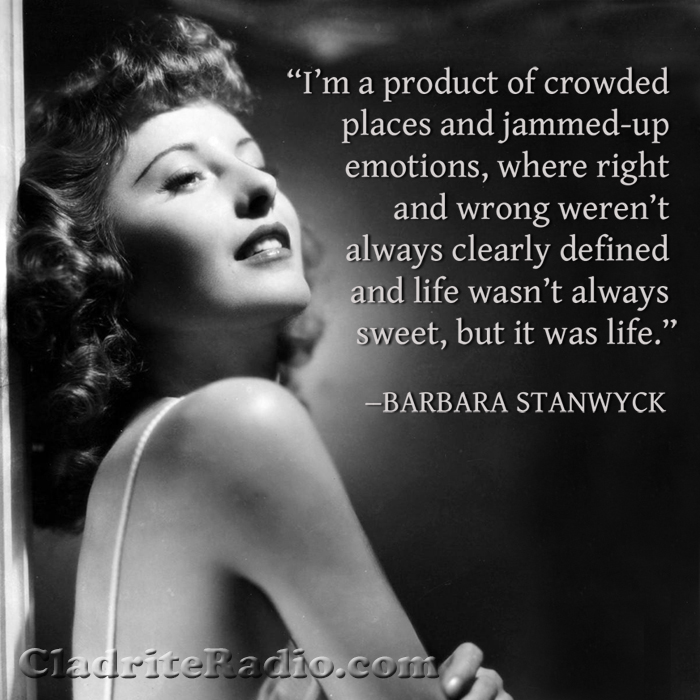

The wonderful Barbara Stanwyck was born Ruby Catherine Stevens in Brooklyn, New York, 109 years ago today. We admire dozens of actresses from the Golden Age of Hollywood, but for our money, Stanwyck was the greatest of them all. Here are 10 BS Did-You-Knows:

- Stanwyck’s older brother, Bert Stevens, was also a busy actor, with more than 400 credits listed at IMDb.com.

- Stanwyck was of English, Scottish, and Irish ancestry.

- Her mother died in a trolley accident when Stanwyck was just four years old. Her father then abandoned Stanwyck and her four siblings to be raised by other members of the family.

- In 1944, the U.S. government named Stanwyck the country’s highest-paid woman.

- Stanwyck’s relationship with her first husband, Frank Fay, is said to have been the inspiration for the 1937 film A Star Is Born.

- Stanwyck attended high school at Erasmus Hall in Brooklyn, but dropped out at 14.

- Stanwyck played characters named Jessica Drummond in two very different movies: My Reputation (1946) and Forty Guns (1957).

- Stanwyck, who was very conservative politically, was a member of The Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals.

- Stanwyck started smoking when she was nine years old.

- Stanwyck has no grave. After she passed away in 1990 due to congestive heart failure and emphysema, she was cremated and her ashes were scattered from a helicopter over Lone Pine, California.

Happy birthday, Barbara Stanwyck, wherever you may be!