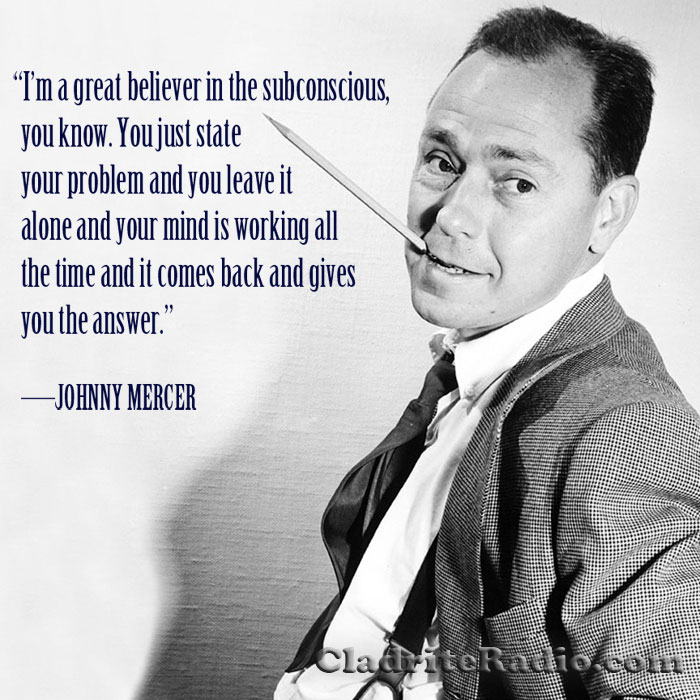

Lyricist, composer and singer Johnny Mercer, one of the greatest lyricists to contribute to the Great American Songbook, was born John Herndon Mercer 107 years ago today in Savannah, Georgia. Here are 10 JM Did-You-Knows:

- Mercer’s father was an attorney; his mother was his father’s secretary before she became his second wife.

- Mercer was exposed to a wide range of African-American music as a child. His aunt took him to minstrel and vaudeville shows, and he spent time with many black playmates (and his family’s servants). He also was drawn to Savannah’s black fishermen and street vendors, as well as African-American church services. As a teenager, he collected records by black artists such as Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith and Louis Armstrong.

- Mercer was singing in church choirs by age six, and within a few years, had demonstrated a penchant for memorizing all the popular songs of the day.

- His family frequently escaped Savannah’s heat at a mountain retreat near Ashville, North Carolina, and it was there that young Mercer learned to dance from none other than Arthur Murray himself.

- Mercer moved to NYC in 1928, taking bit parts as an actor and continuing to work on the songwriting he’d begun to experiment with back in Savannah. He took a job at a brokerage house to pay the bills, and began to sing around town. He once pitched a song to Eddie Cantor, and though Cantor didn’t buy the song, he was very encouraging to Mercer.

- Mercer preferred writing standalone songs to writing for musicals, where the lyrics had to fit the show, so when the revue format gave way to book musicals on Broadway, he moved to Los Angeles and took a job with RKO.

- Mercer founded Capitol Records with songwriter Buddy G. DeSylva and businessman Glenn Wallichs in 1942, investing $25,000. In 1955, he sold his share in the company for $20 million.

- Mercer was married to Ginger Mehan from 1931 until his death in 1976, but he had an on-and-off affair with Judy Garland.

- A fan once wrote Mercer, suggesting the song title I Wanna Be Around (to Pick Up the Pieces When Somebody Breaks Your Heart). Mercer quickly wrote a song by that title, and when it became a hit, he gave the fan half his royalties.

- Mercer was a distant cousin of Gen. George S. Patton.

Happy birthday, Johnny Mercer, wherever you may be!