Here are 10 things you should know about Leon Errol, born 143 years ago today. He enjoyed success in burlesque, vaudeville, Broadway, and motion pictures—both features and shorts.

Tag: Bert Williams

Snapshot in Prose: Ernest Burnett

“My Melancholy Baby” is one of those standards that most folks over a certain age have heard of, but few could, if pressed, sing (we can, we’re proud to say, if only in our atonal, pitchy way). It’s a familiar song title, in other words, but no longer such a familiar song.

We’re guessing even fewer people could name the song’s composer.

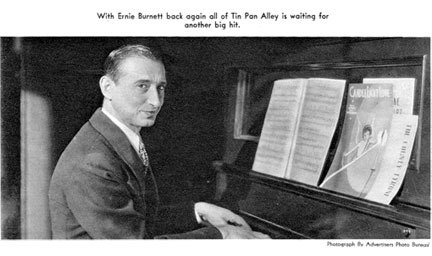

But as we learn in today’s Snapshot in Prose, originally published in 1935, “My Melancholy Baby” was a recurring hit for three decades running in the early years of the last century, the greatest claim to fame for songwriter Ernest Burnett. Burnett, who served in World War I, was once thought to have died in that conflict—no less a figure than Paul Whiteman even announced as much over the radio, as Burnett lay recuperating from tuberculosis in a government-run sanatorium in Arizona—but he came storming back to Broadway to resume his career, and not without success.

But “My Melancholy Baby” remains, to this day, his crowning achievement.

Read to the bottom of the profile, and you’ll find a couple of renditions of the song for your dancing pleasure.