A few dozen pop culture aficionados gathered in the Bronx on Saturday, April 21, 2018, to pay tribute to entertainer Nora Bayes, who was once one of the biggest stars in America.

A few dozen pop culture aficionados gathered in the Bronx on Saturday, April 21, 2018, to pay tribute to entertainer Nora Bayes, who was once one of the biggest stars in America.

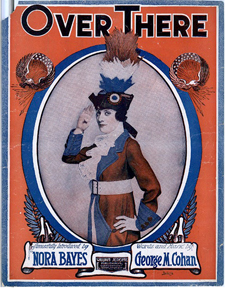

If you’re thinking you’re not familiar with Bayes, think again. You could almost certainly hum a few bars of at least a couple of her biggest hits: Shine On, Harvest Moon, which she cowrote and had a big hit with in 1908, and George M. Cohan‘s Over There, which she popularized in 1917 during the buildup to the USA’s entry into World War I.

Bayes, a popular vaudevillian and Broadway star, was a larger-than-life figure, a diva ahead of her time. One of the highest-paid women in the world at the peak of her career, Bayes, a featured performer in the Ziegfeld Follies, was a rival to Sophie Tucker, a fellow Follies performer who is arguably better remembered today.

While she was still living, Nora Bayes had a West 44th Street Broadway theatre named after her, and her life story was told in a posthumous biopic, Shine on, Harvest Moon (1944), in which she was portrayed by Ann Sheridan (Frances Langford played Bayes in the 1942 Cohan biopic, Yankee Doodle Dandy).

Bayes’ personal life was also memorable: She married a succession of five men in an era when divorce was still scandalous (and not easily achieved).

Bayes’ personal life was also memorable: She married a succession of five men in an era when divorce was still scandalous (and not easily achieved).

When Bayes died of cancer in 1928 at age 48, fans thronged the sidewalks outside her Manhattan townhouse to watch as she was carried away in a silver casket. She was taken to Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, but wasn’t buried right away; instead her remains were stored in a receiving tomb, a temporary resting place typically used only for a short period of time while burial arrangements are being made.

But arrangements for Bayes’ internment weren’t immediately forthcoming; in fact, she remained in that receiving tomb for 18 years, until 1948.

It’s not entirely clear why her fifth husband, Benjamin Friedland, didn’t arrange for her burial sooner. He continued to pay the monthly fees for her temporary…er, digs even after he remarried, and he willingly took on the responsibility of raising the three children Bayes had adopted before she and Friedland were wed.

Friedland never offered a public explanation for the lengthy delay—it’s been suggested (but not confirmed) that he wanted his first wife to buried with him when his time came—and he refused offers from Bayes’ fans and fellow performers to assume the task of making arrangements for her internment.

It was only when Friedland died in 1946 that Bayes’ remains were finally interred, thanks to Friedland’s second wife, Louise Clarke Friedland, who purchased a Woodlawn plot large enough for five coffins and buried Bayes and Friedland side by side (the other three spaces remain unused—when she died in 1973, the second Ms. Friedland opted for cremation).

It was only when Friedland died in 1946 that Bayes’ remains were finally interred, thanks to Friedland’s second wife, Louise Clarke Friedland, who purchased a Woodlawn plot large enough for five coffins and buried Bayes and Friedland side by side (the other three spaces remain unused—when she died in 1973, the second Ms. Friedland opted for cremation).

But though Bayes and Friedland were buried, both graves remained unmarked. Until Saturday, that is.

Last year, Michael Cumella, friend to Cladrite Radio and an expert on the popular culture of the first half of the twentieth century, began to do the legwork needed to finally see stone markers placed on Bayes’ (and Friedland’s) graves. Saturday’s unveiling of the markers was the culmination of months of hard work on Cumella’s part (and Woodlawn officials), and it was a festive occasion. Peter Mintun and Tamar Korn performed Bayes’ biggest hits, a number of Bayes’ original 78s were played on an antique windup phonograph, and a portrait of Ms. Bayes’, painted nearly a century ago and purchased (one might say rescued) a couple of years ago at an area flea market, was put on display for all to enjoy.

We like to think that somewhere Nora Bayes is smiling.