Rudy Vallée only began performing on the radio in 1928, so the idea of penning a memoir in 1930, at the ripe old age of 29, might well be viewed as premature.

But modesty was never Vallée’s strong suit, so it’s perhaps not surprising that he was already itching to begin telling his story.

Here’s Chapter 1 from Vagabond Dreams Come True—enjoy!

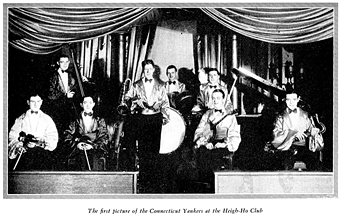

THE SEVEN BOYS WHO WORK WITH ME

us, and their great love, we

would never have succeeded

Thus springs up what is known as the Whiteman office, the Lopez office, the Bernie office, and this work to which they cater is called “outside” or “club” work. This work is sporadic, to be sure; that is, the work is seasonal, depending upon the seasons when debutantes come out, when marriages take place, when fraternal orders celebrate, when students are home for vacation, and when fraternities give their dances, during the football season. Thus, it is either feast or famine. However, most of the representative offices keep a certain number of men employed every week, and the advantage of club work is that sometimes three nights of hard club work pays more than seven nights of steady work. A club job is very hard while it lasts but it pays excellently, since the men usually play steadily from ten in the evening until the wee hours of the morning.

Thus springs up what is known as the Whiteman office, the Lopez office, the Bernie office, and this work to which they cater is called “outside” or “club” work. This work is sporadic, to be sure; that is, the work is seasonal, depending upon the seasons when debutantes come out, when marriages take place, when fraternal orders celebrate, when students are home for vacation, and when fraternities give their dances, during the football season. Thus, it is either feast or famine. However, most of the representative offices keep a certain number of men employed every week, and the advantage of club work is that sometimes three nights of hard club work pays more than seven nights of steady work. A club job is very hard while it lasts but it pays excellently, since the men usually play steadily from ten in the evening until the wee hours of the morning.