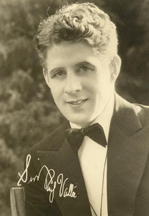

In Chapter Six of Rudy Vallée’s 1930 memoir, Vagabond Dreams Come True, Rudy continues his tutelage on organizing and leading a dance orchestra in the 1930s (we can’t help but wonder how many of Rudy’s “lessons” would still apply today).

Rudy discusses the role showmanship, and especially clowning, plays in a successful orchestra’s performance. And it’s interesting to note from Rudy’s remarks that, even in 1930, most fans attending a live show by their favorite performers made it a practice to request the orchestra’s most popular hits. We wonder if they held up cigarette lighters when requesting an encore at show’s end?

P.S. If you read till the end, you’ll find a streaming recording of one of the songs Rudy discusses in this chapter, “You’ll Do It Someday, So Why Not Now?” (He cleans up the title a little in the book, calling it “You’ll Love Me Someday, So Why Not Now?”, but he’s not fooling us.)

PAGING MR. BARNUM