There’s a antique mall in an old farmer’s market building in downtown Oklahoma City that we try to get to whenever we’re home visiting the family, and in that mall is a particular store that we make it a point to patronize. The owner’s kind of an old grump and some of his stuff’s overpriced, but he has plenty of the sort of paper ephemera we like, and we usually find something to covet, if not purchase.

There’s a antique mall in an old farmer’s market building in downtown Oklahoma City that we try to get to whenever we’re home visiting the family, and in that mall is a particular store that we make it a point to patronize. The owner’s kind of an old grump and some of his stuff’s overpriced, but he has plenty of the sort of paper ephemera we like, and we usually find something to covet, if not purchase.

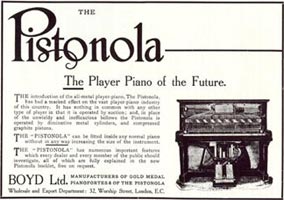

The last time we were in his store, we stumbled upon a shelf filled with piano rolls of the 1920s and ’30s, and our heart skipped a beat. They were much more reasonably priced than many of his other offerings, and the titles were right up our alley, many of them songs frequently heard on Cladrite Radio.

It’s one of the few regrets we have about residing in New York City: Space is at a premium, and we simply don’t have room for a player piano. Would that we did. We’d snap up a couple of dozen of that old grump’s piano rolls in a heartbeat

But we did recently learn of a YouTube channel that eases the pain a bit. AeolianHall1 is the poster’s handle, and his or her channel features a delightful roster of piano roll recordings from the 1930s, the 1920s, and even earlier.

We thought we’d share one of our favorites with you, Pauline Albert’s recording of Irving Berlin‘s 1927 hit “The Song Is Ended (but the Meolody Lingers On). But you really should make it a point to pop over and give AeolianHall1’s extensive collection a good listen.

|