Here are 10 things you should know about Dan Duryea, born 116 years ago today. He worked steadily in theatre, television and pictures and in a variety of genres, but it was by playing bad guys in films noir that he made his most indelible mark.

Tag: The Woman in the Window

Happy Birthday, Dan Duryea!

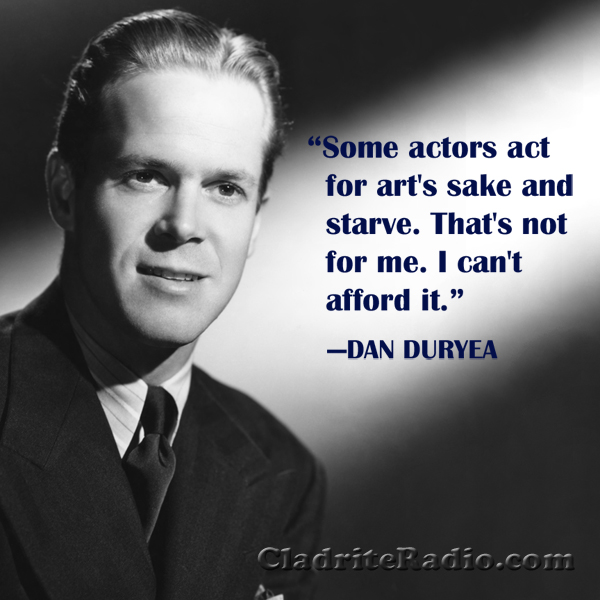

Given his screen persona, Dan Duryea, born 109 years ago today in White Plains, New York, might not strike the average movie buff as an Ivy Leaguer, but he was, in fact, a member of Cornell University’s class of 1928. He majored in English, but was interested in theatre, too. In his senior year, he even succeeded Franchot Tone as president of the college drama society.

Duryea went on to work in advertising for a bit until the stress got to be too much. A mild heart attack in his twenties convinced him to pursue an acting career instead, a move that paid off nicely. He appeared on Broadway in Dead End and The Little Foxes, and it was the latter play that provided his ticket to Hollywood. Though Bette Davis was named to replace his Broadway co-star, Tallulah Bankhead, in the role of Regina Giddens when Sam Goldwyn bought the rights to produce the cinema adaptation of the hit play, Duryea was retained to play her nephew Leo Hubbard, his cinematic bad guy (or, at the very least, his first weasel).

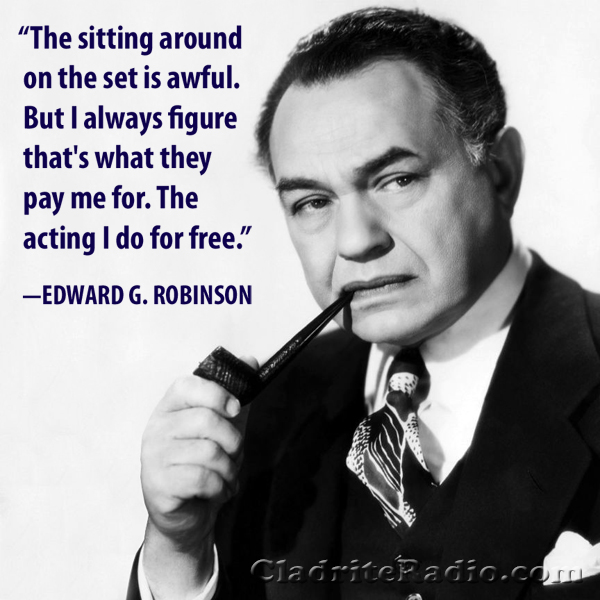

In an early 1950s interview with Hedda Hopper, Duryea claimed that his focus on playing bad guys was intentional, even planned:

“I looked in the mirror and knew with my ‘puss’ and 155-pound weakling body, I couldn’t pass for a leading man, and I had to be different. And I sure had to be courageous, so I chose to be the meanest s.o.b. in the movies … strictly against my mild nature, as I’m an ordinary, peace-loving husband and father. Inasmuch, as I admired fine actors like Richard Widmark, Victor Mature, Robert Mitchum, and others who had made their early marks in the dark, sordid, and guilt-ridden world of film noir; here, indeed, was a market for my talents. I thought the meaner I presented myself, the tougher I was with women, slapping them around in well-produced films where evil and death seem to lurk in every nightmare alley and behind every venetian blind in every seedy apartment, I could find a market for my screen characters.”

We’re not necessarily convinced that Duryea entered the movie business with that much foresight and wisdom, but it sounded good after the fact, and in any case, it’s certainly true that he came to be closely identified with the film noir genre and known for his memorable portrayals of sketchy (at best) characters, in classics such as The Woman in the Window (1944), Scarlet Street (1945),Criss Cross (1949), and Too Late for Tears (1949).

For our money, Dan Duryea was a sort of poor man’s Widmark, but as we see it, there’s not a thing in the world wrong with that.

A nice guy and dedicated family man in real life, Dan Duryea was married to his wife, Helen, for 35 years until her death and was an attentive parent, serving as a scout master and PTA papa to his two sons.

But on screen, he was the sniveling creep you hoped would get his. And while he usually did, he gave as good as he got.

Happy birthday, Mr. Duryea, wherever you may be—you heel, you.

Happy Birthday, Edward G. Robinson!

Edward G. Robinson, born Emmanuel Goldenberg 122 years ago today in Bucharest, Romania, is an actor we’ve long felt doesn’t receive his due. Sure, he’s still remembered, but it’s as a movie star, not an actor—a cliché, almost, who played nothing but gangsters and delivered his lines with a sneer. (“We’re doing things my way, see, or it’ll be just too bad for you, see..”) [Please note: The preceding was not a line of dialogue Mr. Robinson ever actually delivered; we made it up.]

But Edward G. Robinson was very much capable of nuanced and moving performances, and it’s almost a shame that he was so effective in tough guy roles. They made him a star and no doubt put a lot of money in his bank account, but they have colored the public’s perception of Robinson’s talents to this day.

In movies such as Double Indemnity, The Woman in the Window and Scarlet Street, he plays not tough guys, but intellectuals, men who rely on brains rather than brawn or bullets, and in two of those pictures (and in others he appears in), there is a gentleness, even a meekness, to his characters that causes them to be taken advantage of, even victimized.

It’s ironic that Robinson came to be identified with tough guy roles, as in real life he was refined and cultured. He was a serious art connoisseur and a man of the theatre. He even co-authored a play with Jo Swerling.

But nowadays, when a comic attempts to reference the gangster movies of the 1930s, it’s usually Robinson they mimic (whether they realize it or not), and it’s Little Caesar and an assortment of other gangster roles that Robinson is remembered for. Not that he didn’t play them well—he obviously did—but he had much more range as an actor than he is given credit for today, and that’s a shame.

Happy birthday, Mr. Goldenberg, wherever you may be!

Forget the forest; it’s all about the trees

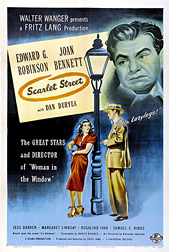

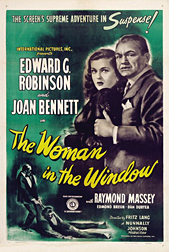

We took in a Fritz Lang double feature yesterday afternoon at Film Forum: Scarlet Street (1945) and The Woman in the Window (1944).

We took in a Fritz Lang double feature yesterday afternoon at Film Forum: Scarlet Street (1945) and The Woman in the Window (1944).

As one might expect from Lang, they were both solid pictures, both in the noir vein and both starring Joan Bennett, Edward G. Robinson, and Dan Duryea.

And yet, in a way, the two pictures are reverse images of one another. Scarlet Street is oddly whimsical throughout; the circumstances—a young woman and her shiftless boyfriend work to take a bank cashier and would-be artist for all he’s worth (which is far less than they imagine it is)—are typical of film noir, but the tone of the performances isn’t. The packed house at Film Forum tittered and chuckled throughout, and we couldn’t help wondering if that was what the filmmakers were aiming for. But they weren’t laughing at any perceived ineptitude; the laughs did seem intended.

But the ending of the picture is as bleak as any classic noir. It was a bit jarring.

The Woman in the Window, on the other hand, takes a more traditional approach to its noir tale of a middle-aged professor and a glamour gal who unintentionally commit murder and spend the rest of the picture trying to avoid having the deed be traced to them. It’s cleverly done and witty, but not nearly as lighthearted as Scarlet Street.

The Woman in the Window, on the other hand, takes a more traditional approach to its noir tale of a middle-aged professor and a glamour gal who unintentionally commit murder and spend the rest of the picture trying to avoid having the deed be traced to them. It’s cleverly done and witty, but not nearly as lighthearted as Scarlet Street.

But the twist ending (don’t worry, we won’t spoil it) takes the picture in a different direction entirely.

Both films are available on DVD and are well worth watching.

As we always do when we’re viewing a pre-1960 picture, we found ourselves watching for small background details, in the decor of the apartments in which the stories took place, the design of the clothing worn by the actors, the terms, slang and otherwise, used in the dialogue. It’s a habit we picked up long ago, as our interest in life as it once lived grew ever more avid.

Our visual scouring when watching an old movie goes even so far as to take note of the titles on a book shelf, if we find a shot that pulls in close enough for us to make them out. In The Woman in the Window, there’s a scene that finds Duryea, playing a lowlife blackmailer (is there any other kind?), is searching for some hidden dough in Bennett’s apartment, and in conducting the search, he pulls down a handful of books from a shelf on the wall.

He leaves a few books behind on that shelf, and in doing so, the title of one of them is made clearly visible (it’s visible on the big screen, at least, which is just one more argument for seeing classic movies in a theatre whenever possible). We made a mental note of the title, for no good reason whatsoever beyond curiosity, with the intention of doing a little digging when we got home.

The book was entitled “30 Clocks Strike the Hour.” We were left wondering whether it was an actual book or a dummy one mocked up by the prop department at MGM. We were inclined toward the latter possibility.

Well, as it turns out, we were wrong. The book is a collection of short stories by Vita Sackville-West, a prominent and prolific English author and poet who penned more than 10 books of poetry, at least 17 novels and short-story collections, and a handful of biographies. Sackville-West is also remembered for the lengthy string of affairs she conducted with a number of prominent women, including one with Virginia Woolf that is said to have inspired the novel Orlando (Ms Sackville-West and her husband, writer and politician Harold George Nicolson, practiced open marriage).

Well, as it turns out, we were wrong. The book is a collection of short stories by Vita Sackville-West, a prominent and prolific English author and poet who penned more than 10 books of poetry, at least 17 novels and short-story collections, and a handful of biographies. Sackville-West is also remembered for the lengthy string of affairs she conducted with a number of prominent women, including one with Virginia Woolf that is said to have inspired the novel Orlando (Ms Sackville-West and her husband, writer and politician Harold George Nicolson, practiced open marriage).

So it likely says more about us than it does of Ms. Sackville-West that not only didn’t we recognize the title of the book, we were previously altogether unaware of her life and career.

But that’s okay. We know about her now, and who knows? We might even pick up a copy of Thirty Clocks Strike the Hour one of these days. After all, if it was good enough for Alice Reed, Bennett’s character in the picture, it is very likely good enough for us.

Having authored a book of our own a few years back, we have to admit we’d get a kick out of seeing our humble little hardback sitting on a shelf during a given scene in a movie, especially a film that eventually comes to be viewed as a classic and is still drawing sold-out houses 66 years after its debut, as is The Woman in the Window.

We like to imagine some guy or gal, ca. 2077, with an interest in the cinema of the early 21st century and an eye for detail, undertaking a search via the web (or whatever has replaced it by then) to find out if our book (and, by extension, we) really existed.

It’s remarkable, really, what one can discover by looking beyond the cinematic forest at the tiniest trees.

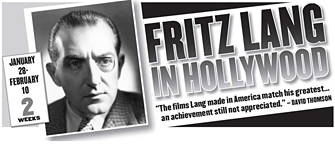

Film Forum fetes Fritz's hits

If you’re anything like us and you happen to reside in or around New York City, you plan to make an almost daily pilgrimage to West Houston over the two weeks for “Fritz Lang in Hollywood,” a two-week retrospective at Film Forum.

If you’re anything like us and you happen to reside in or around New York City, you plan to make an almost daily pilgrimage to West Houston over the two weeks for “Fritz Lang in Hollywood,” a two-week retrospective at Film Forum.

The GermanAustrian-born Lang would be a revered figure in cinematic history even if he’d never set foot in Southern California. Such influential classics as Metropolis (1927), Spione (Spies, 1929), the Dr. Mabuse trilogy, and M (1931) ensure that.

But Lang became a very important director in the United States, too, beginning with his first Hollywood feature, Fury (1936), starring Spencer Tracy and Sylvia Sidney, which closes the Film Forum series as the 22nd of Lang’s 29 Hollywood pictures to be shown.

While in Hollywood, Lang showed a penchant for cinematic takes on pulp fiction—films noir, westerns, thrillers and espionage adventures—but he never settled for by-rote takes on these familiar genres. He gave his pictures a very particular look and dark mood, with the Expressionism of his making films in Germany clearlly influencing his American efforts.

You can’t go wrong with any of the bills during the series, but we especially recmommend the aforementioned Fury on Feb. 10; You Only Live Once (1937), starring Sidney and Henry Fonda, which is paired on Feb. 9th and 10th with Lang’s gangster musical (!) You and Me (1938), and three terrific noir double-bills: The Woman in the Window (1944)/Scarlet Street (1945 on Jan. 30, House by the River (1950)/The Blue Gardenia (1953) on Feb. 8, and the series-opener, The Big Heat (1953)/Human Desire (1954) on Jan. 28-29, both of which star noir royals Glenn Ford and Gloria Grahame.

If you’re familiar with Lang’s work, you’ve no doubt already got this great retrospective marked in your calendar. If you’re not, clear your calendar now and check out the series’ full line-up to plan which pictures you intend to see. You can thank us later.