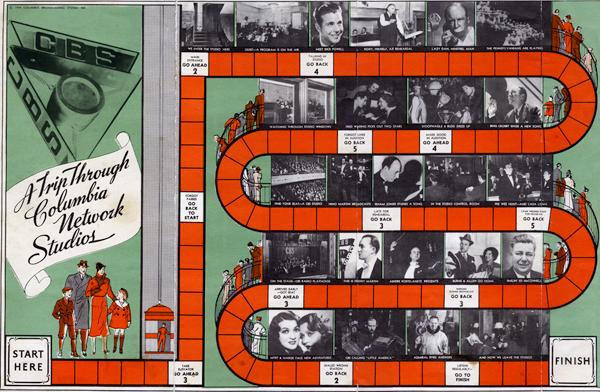

We recently came across this 1934 pamphlet/game board. It was a handout from WCCO, a Minnesota radio station that began operation in 1922 as WLAG (the call letters were changed to WCCO in 1924). But the pamphlet appears to have been issued by the CBS network, not an individual station. It’s our bet that this was distributed by CBS-affiliated stations across the country.

In 1934, CBS was headquartered in New York City (much of their programming originated from Steinway Hall on West 57th Street in Manhattan), and we can only guess that it’s that facility that’s depicted here (but we encourage more astute radio historians than we are to chime in if we’ve got that wrong—Edit: A more astute radio historian did chime in; see the comments below).

Among the famous (and perhaps now not-so-famous) faces you’ll see on your stroll through the studios are crooner Dick Powell, theatrical impresario Samuel “Roxy” Rothafel, Irving Kaufman (in his Lazy Dan, the Minstrel Man mode—really? Blackface on the radio?), Bing Crosby, Fred Waring and his Pennsylvanians, Isham Jones, and George Burns and Gracie Allen, among others.

Click below to see a higher-res version of the image, or to view or download an even larger, higher-res version, click here.