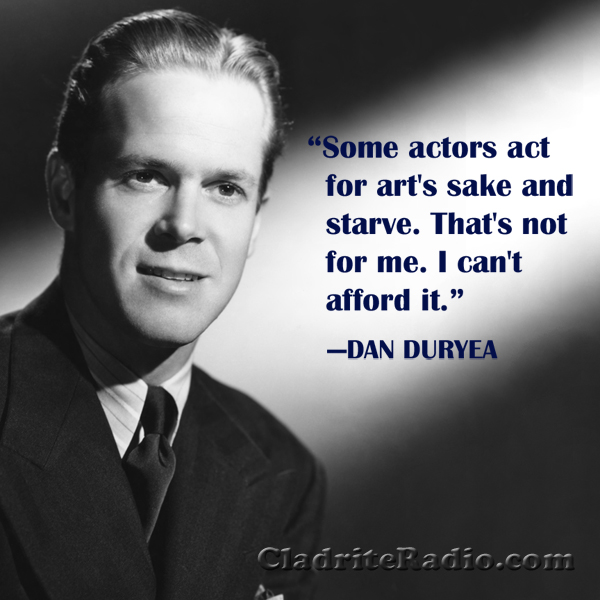

Given his screen persona, Dan Duryea, born 109 years ago today in White Plains, New York, might not strike the average movie buff as an Ivy Leaguer, but he was, in fact, a member of Cornell University’s class of 1928. He majored in English, but was interested in theatre, too. In his senior year, he even succeeded Franchot Tone as president of the college drama society.

Duryea went on to work in advertising for a bit until the stress got to be too much. A mild heart attack in his twenties convinced him to pursue an acting career instead, a move that paid off nicely. He appeared on Broadway in Dead End and The Little Foxes, and it was the latter play that provided his ticket to Hollywood. Though Bette Davis was named to replace his Broadway co-star, Tallulah Bankhead, in the role of Regina Giddens when Sam Goldwyn bought the rights to produce the cinema adaptation of the hit play, Duryea was retained to play her nephew Leo Hubbard, his cinematic bad guy (or, at the very least, his first weasel).

In an early 1950s interview with Hedda Hopper, Duryea claimed that his focus on playing bad guys was intentional, even planned:

“I looked in the mirror and knew with my ‘puss’ and 155-pound weakling body, I couldn’t pass for a leading man, and I had to be different. And I sure had to be courageous, so I chose to be the meanest s.o.b. in the movies … strictly against my mild nature, as I’m an ordinary, peace-loving husband and father. Inasmuch, as I admired fine actors like Richard Widmark, Victor Mature, Robert Mitchum, and others who had made their early marks in the dark, sordid, and guilt-ridden world of film noir; here, indeed, was a market for my talents. I thought the meaner I presented myself, the tougher I was with women, slapping them around in well-produced films where evil and death seem to lurk in every nightmare alley and behind every venetian blind in every seedy apartment, I could find a market for my screen characters.”

We’re not necessarily convinced that Duryea entered the movie business with that much foresight and wisdom, but it sounded good after the fact, and in any case, it’s certainly true that he came to be closely identified with the film noir genre and known for his memorable portrayals of sketchy (at best) characters, in classics such as The Woman in the Window (1944), Scarlet Street (1945),Criss Cross (1949), and Too Late for Tears (1949).

For our money, Dan Duryea was a sort of poor man’s Widmark, but as we see it, there’s not a thing in the world wrong with that.

A nice guy and dedicated family man in real life, Dan Duryea was married to his wife, Helen, for 35 years until her death and was an attentive parent, serving as a scout master and PTA papa to his two sons.

But on screen, he was the sniveling creep you hoped would get his. And while he usually did, he gave as good as he got.

Happy birthday, Mr. Duryea, wherever you may be—you heel, you.