Tag: Rupert Hughes

Formerly Famous: Ursula Parrott

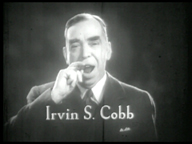

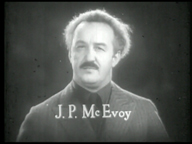

The Woman Accused (1933), starring Cary Grant and Nancy Carroll, was an unusual picture in that it was co-written, as is trumpeted in the movie’s opening credits, by “ten of the world’s greatest authors”: Rupert Hughes, Vicki Baum, Viña Delmar, Irvin S. Cobb, Gertrude Atherton, J. P. McEvoy, Zane Grey, Ursula Parrott, Polan Banks, and Sophie Kerr.

The Woman Accused (1933), starring Cary Grant and Nancy Carroll, was an unusual picture in that it was co-written, as is trumpeted in the movie’s opening credits, by “ten of the world’s greatest authors”: Rupert Hughes, Vicki Baum, Viña Delmar, Irvin S. Cobb, Gertrude Atherton, J. P. McEvoy, Zane Grey, Ursula Parrott, Polan Banks, and Sophie Kerr.

That roster of once-prominent scribes moves one to ponder the fleeting nature of fame. How many of those names are familiar to the average person today? An entirely unscientific survey we conducted found that most folks recognize exactly one: Zane Grey. The others, it seems, are all but forgotten. It’s as if Stephen King, David Sedaris, Dan Brown, Dean Koontz, J. K. Rowling and another handful of today’s most prominent authors teamed to write a serialized novel that was then made into a movie. Would movie buffs in the year 2090, while watching that picture, scratch their heads over the identities of these writers?

We did a little digging on The Woman Accused‘s ten authors and found Parrott most intriguing. She was sort of the Candace Bushnell of her day, trafficking in proto-chick lit that examined the trials and tribulations endured by the “New Woman” of the 1920s and the freshly minted morals by which she lived.

Born in Boston in 1899, Parrott graduated from Radcliffe. She moved to Greenwich Village in 1920, where she married the first of her four husbands, Lindesay Marc Parrott, in 1922. The Parrotts divorced in 1925. Parrott wrote what she knew in composing her first novel, Ex-Wife, in 1929. The book’s subject matter was so scandalous in its time that it was initially published anonymously. Despite that (or perhaps because of it), it sold more than 100,000 copies the first year. Ex-Wife tells the tale of Pat and Peter, a married couple in their twenties who are convinced they needn’t follow the old rules in the pursuit of marital bliss. But when Peter, who has strayed, learns that Pat has done the same (just once, and in a tipsy moment of emotional weakness), his attitude toward her behavior is no longer so modern.

Born in Boston in 1899, Parrott graduated from Radcliffe. She moved to Greenwich Village in 1920, where she married the first of her four husbands, Lindesay Marc Parrott, in 1922. The Parrotts divorced in 1925. Parrott wrote what she knew in composing her first novel, Ex-Wife, in 1929. The book’s subject matter was so scandalous in its time that it was initially published anonymously. Despite that (or perhaps because of it), it sold more than 100,000 copies the first year. Ex-Wife tells the tale of Pat and Peter, a married couple in their twenties who are convinced they needn’t follow the old rules in the pursuit of marital bliss. But when Peter, who has strayed, learns that Pat has done the same (just once, and in a tipsy moment of emotional weakness), his attitude toward her behavior is no longer so modern.

The rest of the novel is devoted to Pat’s coming to terms with her new status as an ex-wife. From our 21st century perspective, Pat’s post-split behavior is not especially shocking—she allows herself a few dispassionate flings and submits to the abortion of a pregnancy for which Peter is responsible. Having moved out of the apartment she shared with Peter, Pat rooms with Lucia, a woman in her thirties who, having already undergone the transition from wife to ex-wife, serves as a soothing and encouraging mentor to Pat. They are two fashionable, well-read, cosmopolitan women navigating an existence that more closely resembles life in 2011 than one might expect.

Author Francine Prose, in her introduction to the 1989 reissue of Ex-Wife wrote: “It’s striking how much of Ex-Wife seems far less dated than many of [F. Scott] Fitzgerald‘s Jazz Age stories”—and it’s true. Pat’s daily life comes off as remarkably similar to those led by so many urban, urbane women today.

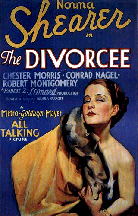

MGM paid the then-extravagant sum of $20,000 fro the film rights to Ex-Wife, though the resulting picture, 1930’s The Divorcee, starring Norma Shearer and Chester Morris, is at best a loose adaptation of Parrott’s novel. That didn’t keep her from answering the door when Hollywood again came knocking. Between 1930 and 1936, eight more pictures were made based on Parrott’s novel and stories.

MGM paid the then-extravagant sum of $20,000 fro the film rights to Ex-Wife, though the resulting picture, 1930’s The Divorcee, starring Norma Shearer and Chester Morris, is at best a loose adaptation of Parrott’s novel. That didn’t keep her from answering the door when Hollywood again came knocking. Between 1930 and 1936, eight more pictures were made based on Parrott’s novel and stories.

As a writer, Parrott was at her most successful between 1929 and the early 1940s. Her son has estimated that she earned in the neighborhood of $700,000—between $8-$10 million in today’s dollars—over that span. But Parrott spent the money as quickly as she made it, and when her career began a slow but steady slide in the ’40s, there was little left to show for her successes.

Like her fiction, Parrott’s life was not without its marital disruptions and scandals. Wed and divorced four times, she found herself hauled into court in 1943 for helping a young soldier escape from military prison. What’s more, the soldier was accused of trafficking in marijuana. Parrott was also reportedly the victim of numerous attempts at blackmail, and in 1953 she was again in the news when, as Time magazine reported, “her hotel presented a $225.20 bill and refused to accept her check.” Parrott spent 30 hours in a jail in Delaware County, Pennsylvania, with her French poodle, Coco.

In 1957, Ursula Parrott died of cancer at age 58. Her final days were spent in the charity ward of a New York City hospital. Today, the once-celebrated Parrott is so little remembered that only recently was she finally given an entry at Wikipedia, that online repository for otherwise forgotten figures. When first we composed this account, in the summer of 2010, no entry for her was to be found there.

This article originally appeared in the Fall/Winter 2010 issue of Zelda, the Magazine of the Vintage Nouveau.

Fiction’s Fleeting Fame

We recently watched The Woman Accused (1933), a mystery starring a very young Cary Grant and a very lovely Nancy Carroll. The screenplay, written by Bayard Veiller, was adapted from a serialized novella in Liberty magazine in which each segment was written by one of ten popular authors: Rupert Hughes, Vicki Baum, Viña Delmar, Irvin S. Cobb, Gertrude Atherton, J.P. McEvoy, Zane Grey, Ursula Parrott, Polan Banks, and Sophie Kerr.

The question that arose for us as these authors were seen during the opening credits in a series of brief, silent cameos was, why don’t we know more of these names? The movie’s credits describe them “ten of the world’s greatest authors,” for Pete’s sake. How can we not have an inkling who most of them are?

Perhaps it reveals us as shallow and poorly read, but the only name we recognized was western novelist Grey; the rest were unknown to us (though as we researched their careers a bit, we found there were several names we should have recognized).

So, before you read on, stop and think: How many can of these ten authors of yesteryear are you familiar with? We’ve admittedly set the bar pretty low, to our shame, so surely you’ll recognize more of the names than we did. Once you’ve come up with a total, then click on the images below to learn more about each writer.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|