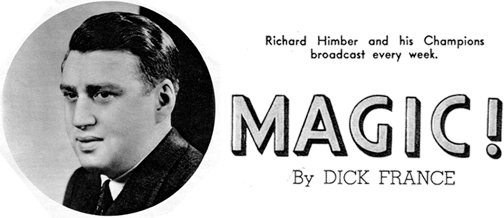

For those who think outrage over lyrics and rhythms in popular music began with those decrying gangsta rap, with Tipper Gore‘s penchant for warning stickers, or even those fuddy-duddies who were outraged by the onstage antics of Elvis Presley and other rockers in the 1950s, what follows may come be an eye-opener For, while Snapshot in Prose usually profiles a popular Cladrite Radio performer at a particular point in his or her career, this week, we’re sharing a 1934 essay from Popular Songs magazine bemoaning the intrusion into the popular music and radio broadcasts of the day by would-be moral arbiters armed with newly sharpened censor’s scissors.

It’s interesting to note that the article mentions the “purification” of movies, too, given that 1934 was the year that Breen Production Code began to be strictly enforced by Will Hayes and his associates.

Recently, just when radio censorship was quieting down—and movies were getting the brunt of it from the Decency Leagues—five of the most famous orchestra leaders banded together for the announced purpose of protecting the public’s delicate ears from offensive lyrics.

Recently, just when radio censorship was quieting down—and movies were getting the brunt of it from the Decency Leagues—five of the most famous orchestra leaders banded together for the announced purpose of protecting the public’s delicate ears from offensive lyrics.