Here are 10 things you should know about Jean Hersholt, born 138 years ago today. He enjoyed great success in pictures and radio, but is perhaps best remembered for his humanitarian endeavors.

Tag: Ricardo Cortez

10 Things You Should Know About Ricardo Cortez

Here are 10 things you should know about Ricardo Cortez, born 123 years ago today. The not-so-Latin Lover enjoyed three decades of success in Hollywood before becoming a stockbroker on Wall Street.

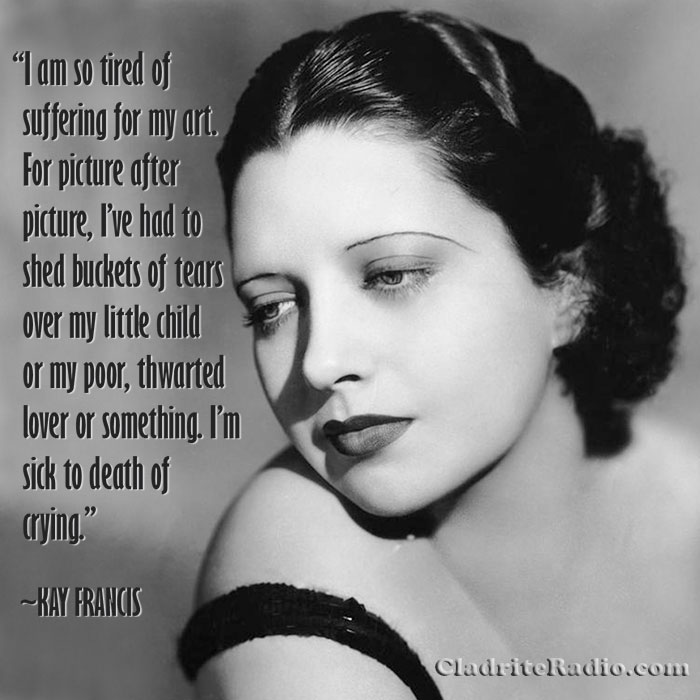

Happy 112th Birthday, Kay Francis!

Fashion plate and Queen of the Women’s Pictures Kay Francis was born Katherine Edwina Gibbs 112 years ago today in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Here are 10 KF Did-You-Knows:

- Though Francis was born in Oklahoma City, she didn’t live there long. Much of her childhood was spent on the road with her mother, Katherine Clinton, who was an actress. At age 17, Francis, who was then attending Katherine Gibbs Secretarial School in New York City, married the first of her five husbands—one James Dwight Francis, member of a prominent (and well-to-do) Pittsfield, Massachusetts, family. That marriage, like the four other matrimonial knots Francis would eventually tie, unraveled in relatively short order.

- Shortly after her 1925 divorce, Francis decided to follow her mother’s example and pursue a life on the stage. In November of that year, she made her Broadway debut as the Player Queen in a modern-dress version of Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

- After a handful more Broadway roles, Walter Huston, her costar in the 1928 production of Elmer the Great, encouraged her to take a screen test for Paramount Pictures. She did, and was given roles in Gentlemen of the Press (1929) and the Marx Brothers‘ first picture, The Cocoanuts (1929), both of which were filmed at Paramount’s Astoria Studios in Queens, NY.

- Soon thereafter, Francis moved to Hollywood where her striking looks and model’s figure (she stood 5’9″, very tall for an actress at the time) helped her career to ascend. From 1929 to 1931, she appeared in more than twenty films.

- Warner Brothers wooed Francis away from Paramount in 1932, and it was there that she experienced her greatest success. By the mid-’30s, Francis was the queen of the Warner Brothers lot and one of the highest-paid people in the United States. From 1930-37, Francis appeared on the cover of more than 38 movie magazines, second only to Shirley Temple (who racked an astonishing 138 covers over that span).

- At Warner Brothers, Kay became known as a clotheshorse. Her ability to wear stylish clothes well was highly valued by the studio and admired by fans; in fact, she eventually came to feel that Warner Brothers put more more of a focus on her on-screen wardrobe than her film’s scripts, as she came to be unalterably associated with the sort of weepy melodramas that were then known as “women’s pictures.” We fully understand the frustration she felt at the time, but we’ll admit that we love those pictures and adore Francis’ performances in them.

- Francis’ great success came in spite of a noticable speech impediment: She pronounced R’s as W’s (ala Elmer Fudd). As such, our favorite line of Kay Francis dialogue appears in Mandalay (1934), which was directed by Michael Curtiz and in which Kay starred with Ricardo Cortez, Lyle Talbot, and Warner Oland. It’s great fun to hear her intone, “Gwegowy, we awwive at Mandalay tomowwow.”

- Francis’ personal life was something of a mess. An exceedingly liberated person, sexually, she slept with both men and with women—and plenty of them, and none of her five marriages lasted very long.

- Francis’s career fell as quickly as it had risen. She was through with the movies (or perhaps vice versa) by 1946, when she appeared in her final picture, Wife Wanted, a budget quickie made for the infamous Poverty Row studio Monogram Pictures. Aside from some stage work in the late ’40s and a couple of TV appearences in the early ’50s, she avoided the spotlight thereafter and was largely forgotten by the public (until Turner Classic Movies began to feature her pictures prominently in its programming and her star again rose among old-movie buffs).

- When she died in 1968 of breast cancer, Kay Francis left more than one million dollars to The Seeing Eye, Inc., an organization that trains guide dogs for the blind.

Happy birthday, Kay Francis, wherever you may be!

365 Nights in Hollywood: Reckless Reels

RECKLESS REELS

. . . a jazz band . . . colored spotlights . . . evening gowns . . . and stiff shirts . . . laughter . . . silver flasks . . . smacked lips . . . bluish-grey clouds of lingering smoke . . . The Biltmore ballroom on Saturday night . . . the new playground of the movie folk . . . Art Hickman . . .

. . . a jazz band . . . colored spotlights . . . evening gowns . . . and stiff shirts . . . laughter . . . silver flasks . . . smacked lips . . . bluish-grey clouds of lingering smoke . . . The Biltmore ballroom on Saturday night . . . the new playground of the movie folk . . . Art Hickman . . . In Pwaise of Kay Francis

We’ve shared in this space before how fond we are of actress Kay Francis‘s oeuvre. Her movies, once called “women’s pictures,” would likely be dubbed “soap operas” by most observers today, but whatever tag you choose, the chance to see Kay suffer (she almost always suffered), adorned all the while in elegant gowns designed by the likes of Orry-Kelly and Adrian, is one not to be missed.

We’ve shared in this space before how fond we are of actress Kay Francis‘s oeuvre. Her movies, once called “women’s pictures,” would likely be dubbed “soap operas” by most observers today, but whatever tag you choose, the chance to see Kay suffer (she almost always suffered), adorned all the while in elegant gowns designed by the likes of Orry-Kelly and Adrian, is one not to be missed.

One attribute that makes Kay especially appealing is that she has one tiny flaw as an actress: She had trouble with her Rs, much as Elmer Fudd (opposite whom she never starred) struggled with his. To make it clearer for the uninitiated, Kay, were she still with us and if asked to introduce herself, would pronounce her own name, “Kay Fwancis.”

A few days back, we reveled in watching Mandalay (1934), which was directed by Michael Curtiz and in which Kay starred with Ricardo Cortez, Lyle Talbot, and Warner Oland. It’s a terribly entertaining picture, by any measure, but we were especially delighted to hear perhaps the best Kay Francis line (or the worst, depending upon one’s viewpoint) ever written:

“Gregory, we arrive at Mandalay tomorrow.”

(As you’ll note, we’ve opted to take the high road in spelling out the line as it was written, as opposed to going the phonetic route. You can hear that for yourself below.)