Here are 10 things you should know about Billy Wilder, born 116 years ago today. By virtually any standard, he was one of the ten greatest film makers in history.

Tag: Raymond Chandler

Goodbye to Another Glorious Gal: Dorothy Malone

We were sorry to learn that Dorothy Malone had died, just days short of her 93rd birthday. She enjoyed a long career in motion pictures and television, mostly playing bad girls, but to us, she’ll always be the most memorable bookstore employee in the history of the movies, and if you doubt us on this, just watch this scene with Humphrey Bogart from The Big Sleep (1946).

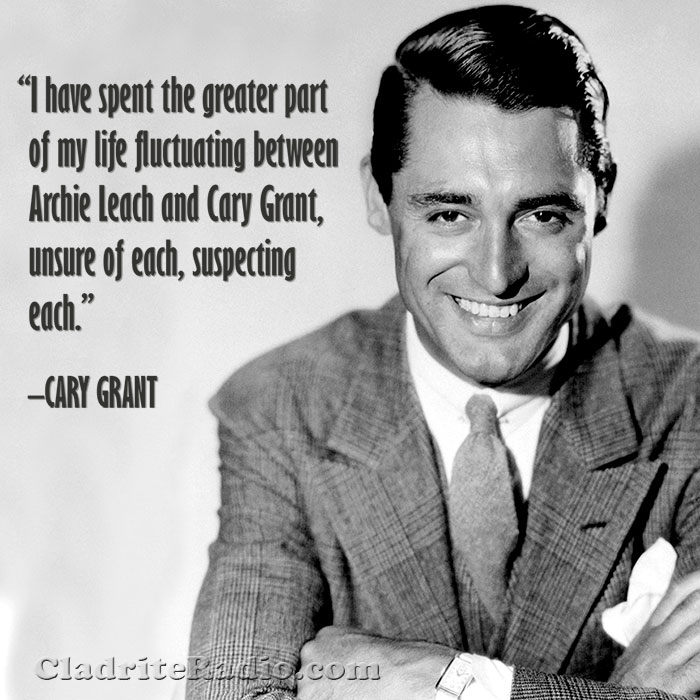

Happy 113th Birthday, Cary Grant!

The great Cary Grant was born Archibald Alexander Leach 113 years ago today in Horfield, a suburb of Bristol, England. Here are 10 CG Did-You-Knows:

- Grant’s parents worked in the garment industry—his father as a tailor’s presser; his mother as a seamstress. His older brother, William, died very young of tuberculous meningitis.

- Grant showed an interest in performing at a very early age, and his mother, who was otherwise very cautious regarding his upbringing after the death of his older brother, encouraged him in pursuing this interest.

- When Grant was just nine years old, his father had his mother placed in a mental institution, telling Grant she was away on holiday. He later told Grant that his mother had died—she had not. Grant didn’t learn she was still alive until twenty years later.

- By his early teens, Grant was performing as a stilt walker with a touring group of acrobats. When he was 16, the troupe traveled to New York City, where it enjoyed nine-month run at the Hippodrome—at that time the largest theatre in the world—before touring the country in vaudeville.

- When the time came for the troupe to return to England, Grant and a few of his fellow performers decided to remain in the U.S. Grant returned to NYC and continued to work, first in vaudeville and then the legitimate theatre, which eventually led to a contract with Paramount Pictures. He made his debut in 1932 in a comedy called This Is the Night that also starred Lili Damita, Charles Ruggles, Roland Young and Thelma Todd.

- Douglas Fairbanks was a key role model for Grant, who shared the star’s good looks and athleticism (Grant had met Fairbanks aboard ship when he first crossed the Atlantic bound for NYC).

- Ian Fleming is said to have based the character of James Bond in part on Grant (we think he’d have made a great Bond), and Raymond Chandler once wrote, “If I had ever an opportunity of selecting the movie actor who would best represent [Philip] Marlowe to my mind, I think it would have been Cary Grant.”

- A telephoned complaint from Grant, who was staying at the Plaza Hotel in NYC, to Conrad Hilton, who was in Istanbul at the time, convinced the hotel czar that the Plaza should serve two full English muffins with room service breakfasts, rather than the one-and-a-half they had been serving.

- Grant donated his entire salary of $137,000 from The Philadelphia Story (1940) to the British War Relief Fund. Four years later, he donated his salary of $160,000 for Arsenic and Old Lace to British War Relief, the USO and the Red Cross.

- Grant was a big fan of Elvis Presley and can be spotted in the audience and backstage in Presley’s concert documentary Elvis: That’s the Way It Is (1970).

Happy birthday, Cary Grant, wherever you may be!

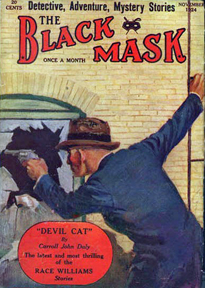

Dashiell Hammett: Getting Witty With It

We generally prefer Raymond Chandler to Dashiell Hammett, as much for Chandler’s wit as anything else, but we’ve been reading some of Hammett’s early Continental Op short stories of late and very much enjoying them, especially a passage from a novelette called The Golden Horseshoe that ran in Black Mask magazine in November 1924.

We generally prefer Raymond Chandler to Dashiell Hammett, as much for Chandler’s wit as anything else, but we’ve been reading some of Hammett’s early Continental Op short stories of late and very much enjoying them, especially a passage from a novelette called The Golden Horseshoe that ran in Black Mask magazine in November 1924.

In this scene, Hammett’s short but rotund detective is in Tijuana tracking down a dissolute poet who is on the lam. The Op has just entered the bar that gives the story its name when the reader is treated to the following first-person passage:

I walked down the room and sat at a table in one of the stalls. A lanky girl who had done something to her hair that made it purple was camped beside me before I had settled in my seat.

“Buy me a little drink?” she asked.

The face she made at me was probably meant for a smile. Whatever it was, it beat me. I was afraid she’d do it again, so I surrendered.

We don’t mind admitting that made us laugh out loud, something we’ve not often done when reading Hammett. Nicely played, sir. Nicely played, indeed.

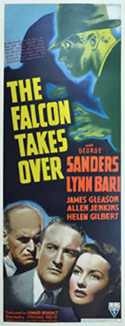

A Frothier, Funnier ‘Farewell, My Lovely’

As we advised you to do, we recorded the first eleven entries in RKO’s “The Falcon” series of mysteries on TCM the other day, and by last night, we’d worked our way up to watching the third one, The Falcon Takes Over.

As we advised you to do, we recorded the first eleven entries in RKO’s “The Falcon” series of mysteries on TCM the other day, and by last night, we’d worked our way up to watching the third one, The Falcon Takes Over.

The Falcon movies aren’t great, but they have a certain frothy charm, the repartee’s enjoyable enough, and at least some of them feature both Allen Jenkins and James Gleason in supporting roles, and that’s a combination that’s hard to beat.

We were especially looking forward to this picture because it’s based on Raymond Chandler‘s Farewell, My Lovely. In this version, it’s George Sanders as The Falcon, not Philip Marlowe, who solves the crime, but it was fun to see a familiar story played out in a different style, a different city (NYC rather than Los Angeles) and with a different set of characters.

One recognizes the source material right away, as just two minutes in, Moose Malloy has already made an appearance, and his name is…Moose Malloy. And the lost love he’s trying to track down is named Velma.

In fact, the filmmakers didn’t bother to change many of the characters’ names: Jessie Florian, Jules Amthor, Ann Riordan and Laird Burnett are all present and accounted for.

The Falcon Takes Over doesn’t stack up to Murder, My Sweet (1944) or Farewell, My Lovely (1975); it’s an entirely different kind of picture. But it is just smidge darker than the typical Falcon picture, and we found that suited us just fine.