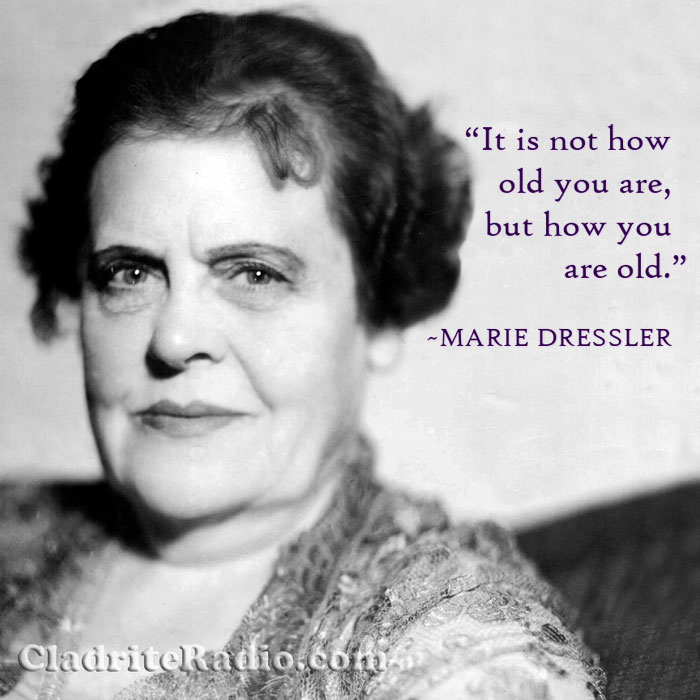

Beloved character actress and comedian Marie Dressler was born Leila Marie Koerber 148 years ago today in Cobourg, Ontario. Here are 10 MD Did-You-Knows:

- Dressler’s father was a music teacher and her mother a musician. When she was still a child, her family moved to the United States, residing in Michigan and Ohio. She grew appearing in amateur theatricals.

- At 14, Dressler left home, lying about her age that she might join a traveling stock company that played mostly in the Midwest. Her older sister, Bonita, also worked with the stock company for a time before leaving to get married. Much of Dressler’s early stage work was in light opera.

- Dressler made her Broadway debut in 1892 in Waldemar, the Robber of the Rhine, a production that enjoyed a brief five-week run. Dressler, who stood 5′ 7″ and weighed 200 pounds, had dreamed of being an operatic diva or a tragedienne, but the author of Waldemar, Maurice Barrymore, father to Lionel, John and Ethel, convinced her that comedic roles would suit her best.

- Dressler’s first starring role came in 1896 in The Lady Slaver, which played for two years at the Casino Theatre.

- Throughout the 1900s and ’10, Dressler kept busy in Broadway productions and in vaudeville, and during World War I, she toured the country, selling Liberty bonds and entertaining the troops.

- Aside from cameo roles playing herself in a pair of film shorts, Dressler’s movie debut came in 1914 at age 44 when fellow Canadian Mack Sennett hired her to star opposite Charlie Chaplin (in a villainous, non-Tramp role) in Tillie’s Punctured Romance, one of the first full-length, six-reel motion picture comedies. The movie was a hit, and Dressler continued to enjoy success in film comedies into the 1920s.

- Her movie career on the wane in the late ’20s, Dressler, now in her late 50s, was considering taking a position as a housekeeper on Long Island—another story has it that she was on the verge of committing suicide—when screenwriter Frances Marion convinced MGM to cast her in The Callahans and the Murphys (1927). That hit picture revived her career.

- Dressler won the Best Actress Oscar for Min and Bill (1930), the first of three popular pictures she would make with Wallace Beery. Only the fourth actress to win that award, she was the third Canadian in a role to do so (after Mary Pickford and Norma Shearer). She received the award the day after her 63rd birthday.

- At age 65, Dressler was named the top box-office draw of 1933 by the Motion Picture Herald.

- The house Dressler was born in Cobourg still stands. Known today as the Marie Dressler House, it was a restaurant from 1937 through 1989, when it was damaged by fire. After being restored, it served as the office for the Cobourg Chamber of Commerce for a time until it was transoformed into a Marie Dressler museum and information center for tourists visiting Cobourg.

Happy birthday, Marie Dressler, wherever you may be!