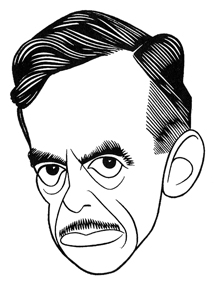

In this chapter from his 1932 book, Times Square Tintypes, Broadway columnist Sidney Skolsky profiles playwright Eugene O’Neill.

THE GREAT GOD O’NEILL

EUGENE O’NEILL. He is the only Broadway playwright who was born in Times Square. He was born in the Barrett House, now the Hotel Cadillac, at Forty-third Street and Broadway. The date: October 16, 1888.

When writing he uses either pen and ink or a typewriter. It merely depends on which is handy. Revising a play annoys him.

His father was James O’Neill—an actor famous for his portrayal of the Count of Monte Cristo. His mother, a fine pianist, attended a convent with the mother of George Jean Nathan.

He’s a great swimmer and doesn’t mind cold water.

Night life doesn’t appeal to him. He made one tour of the night clubs. It was his last.

Never attends the openings of his plays. In fact he seldom goes to a theater. He’s rather read a play than see it performed.

While at Provincetown, a feeble-minded lad of six took a great liking to him. One day while sitting on the beach the boy asked: “What is beyond the Point? What is beyond the sea? What is beyond Europe?” O’Neill answered, “The horizon.” “But,” persisted the boy, “what is beyond the horizon?”

Could grow a beard in ten days if he didn’t shave.

His father, who said he never would be a great playwright, lived to see his son’s first success, Beyond the Horizon.

He hasn’t touched a drop of liquor in the last three years.

In his youth Jack London, Joseph Conrad and Rudyard Kipling were his favorite authors. Today Nietzsche is his literary idol.

He can’t walk a mile without meeting an old friend who asks for money. He gives.

After the opening of Strange Interlude he chance to meet an old seafaring friend. O’Neill asked what he was doing, and the friend replied, “Oh, I’ve married and settled down. Got a nice little business and doing pretty good. And you, Gene, are you still working the boats?”

Reads all the reviews of his plays. He claims he knows the good critics from the bad ones.

He seldom talks unless he has something to say.

While writing he hates to be disturbed. When working at Provincetown he tacked this sign outside his door: “Go to hell.”

Is crazy about prize fights and the six-day bicycle races. When in town he will go to anything at Madison Square Garden. The only person he expressed a desire to meet was Tex Rickard.

His full name is Eugene Gladstone O’Neill. Lately he discarded the middle name entirely.

Once, when a mere infant, he was very ill in Chicago. George Tyler, then his father’s manager, ran about the streets of that city at three in the morning for a doctor.

Is always making notes for future plays. He wrote the notes for his first plays in the memorandum section of that grand publication, The Bartender’s Guide.

He likes to be alone.

He had three favorite haunts. One was Jimmy the Priest’s saloon, a waterfront dive. He later made use of this locale in Anna Christie. Another was “Hell’s Hole,” a Greenwich Village restaurant. The third was the Old Garden Hotel, which was situated on the northeast corner of Madison Avenue and Twenty-seventh Street. Here he met many people of the sporting world. A former bicycle rider (now a megaphone shouter on a sightseeing bus) he met there is still a pal of his.

It took him three years to write Strange Interlude. He had only six of the nine acts completed when he sold the play to the Theatre Guild.

He is especially fond of fine linen.

When in New York he lives in a secondary hotel. A place no one would ever think of looking for him.

He has huge hands.

For every play he draws sketches suggesting designs for the sets.

Of his own work he prefers, The Hairy Ape, The Straw (this he considers the best of his naturalistic plays), Marco Millions, Strange Interlude and Lazarus Laughed. The last is to be produced next year by the Moscow Art Theatre.

He takes great delight in recounting droll stories. Tells them with feeling and skill.

While attending Professor Baker’s class at Harvard he almost ruined the college careers of John Colton and Johnny Weaver by filling them full of beer.

Is now living in France. He does not intend to return to America for some years.

His first book, Thirst and Other One-Act Plays, was published at his expense.

All of his original manuscripts are in his possession despite offers in five figures for them.

He writes important messages which are not to be breathed to a soul, on the back of a postal card.

In Shanghai, on his recent trip around the world, he was a called a faker posing as Eugene O’Neill.