This is our final offering from Hollywood Undressed, a 1931 memoir attributed to the assistant of masseuse and health guru Sylvia Ulback, a.k.a. Sylvia of Hollywood (but actually ghost-written for Sylvia by newspaper reporter and screenwriter James Whittaker).

The second part of the book comprises Sylvia’s dietary and nutritional theories, and we weren’t going to share those here (they’re a little on the dry side), but we decided to say goodbye to Sylvia with the first chapter of that section of the book, which shares daily menus from the diets Sylvia assigned her various and sundry celebrity clients. “Who wouldn’t want to eat like Gloria Swanson or Constance Bennett for a day?” we asked ourselves.

DIET AND WHOLESOME COOKING

1. FOOD AND ITS PREPARATION

BELIEVE it or not, the object of a first-class masseuse’s business is to get rid of patients. If she’s on the level, the masseuse aims to send the patient away in good condition and hopes never to see her again. In this respect, massage is like the medical profession. The doctors too (the decent ones) do their level best to ruin their own racket and nothing is so satisfactory as a patient cured—which is a patient lost.

In Hollywood, Sylvia is reaching the point where her hob, for having been done too well, shows diminishing returns. Which is as it should be. And Sylvia, far from moaning over the fact, is as pleased as the kid who broke up the game by slamming the only ball into the river for a home run. Bit by bit, one by one, the respectable and representative percentage of Hollywood film people who are listed on the boss’s books have been made over and educated to the point where they are the caretakers of their own waistlines and do not need professional supervision at thirty dollars an hour.

If the boss can take it that way, far be it from me to show a meaner spirit. So—

Hurrah! I got fired.

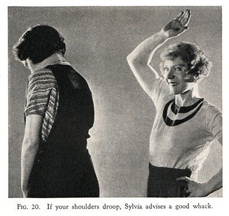

It isn’t the massage that makes these people their own conditioners. The pounding can, and does, effect a speedy correction of overweight, underweight and some of the other deviations from the beautiful normal. But we can’t give any mileage guarantees in our business. A waistline bought on the massaging slab won’t last from now until next Sunday unless the buyer coöperates in the upkeep. With every treatment given in our back room goes a lecture on diet. The boss spiels it out while she’s working, something like this:

“No more fried food—“

Wham!

“Cut out sea-food.”

Ouch.

“Turn over. And listen: lay off the liquor.”

Our customers all go through the same phases. At first they pay no attention to the diet instructions, figuring that the treatments will be absolution for their sins of the table. Sylvia’s invariable procedure, after a week or so of this kind of dishonesty, is to lock the patient out. It makes no difference who the patient is. Some of our most famous patients have been through the disciplining experience of being refused treatment. They eat, drink, live and, to a certain extent, dress as Sylvia prescribes, or they are locked out until they come back in penitent mood—which they all do. Thereafter, there are frequent backslidings. But Sylvia screams and threatens, periodically refuses treatment, and the backslidings become fewer and farther between. The great time to complete the dietary education of a Hollywood movie girl is during one of those interludes (they all pass through them) when the last picture contract is dead and the new one hasn’t been offered. Then, living on credit, running up bills, frightened, chastened, ready to listen to reason, the over-size babies can be taught something. In the long run, invariably, the knowledge is finally appreciated. Good dieting is good eating. When they find that out, the boss has done all she can do for a patient. Good-by patient.

The proposition, here, is to sum up Sylvia’s diet knowledge as it was brought to bear on the people of Part One, taking them in order of their appearance in these pages. As will become apparent as we go along, the boss handles diet problems with a dual point of view: the elements of the diet, and their preparation. Of the two, the latter is much the more important. A pork chop, properly cooking, would be a much better diet dish than a chicken wing fried in fat and ignorance. The place where the chemistry, quality and suitability of your food is decided is not in a scientific tract setting forth the calorie, protein, vitamin contents of this and that raw product; it is not in the package from the patent food manufacturer; it is not in test-tubes, treatises and tabulated statistics; it is over the burner of your kitchen range. There you may negotiate the miracle of your physical regeneration. There also, you may concoct an assortment of deadly poisons from the evil effects of which not even Sylvia’s fists, pounding at their merriest, can deliver you.

2. MARIE DRESSLER’S “AS IS” DIET

MARIE DRESSLER, as has been told, went through a period in Hollywood when, for business reasons, she put up a million-dollar front. By way of awing the financial executives of a company which was trying desperately to circumscribe her salary demands, she set up a semi-royal establishment in a turreted castle of the Hollywood hills. An unexpected result of this purely political maneuver was that idleness, plus a Filipino cook with an oriental imagination, began to tell on her midsection. Sylvia had to put her foot down.