Any old movie fan can quickly come up with a list of stars whose name in the opening credits is reason enough to give a motion picture a look.

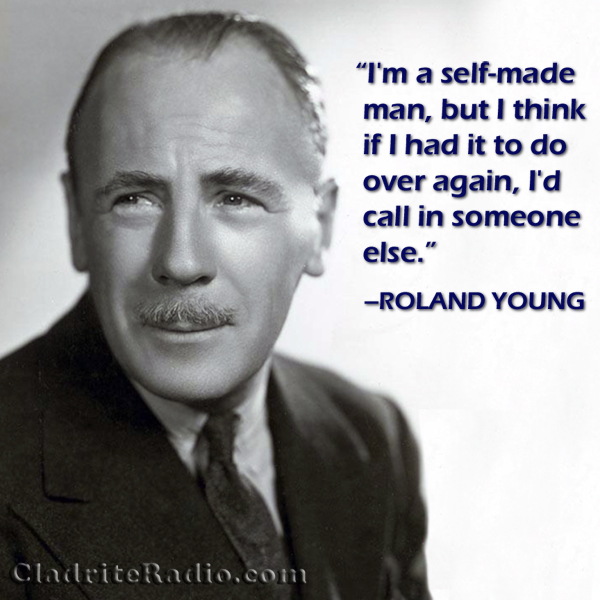

But we suspect that only true aficionados would include the name Roland Young, who was born 128 years ago today, on that list.

Well, you can count us in the latter group. Mr. Young, for our money, is among the elite of motion picture stars of the 1930s and ’40s.

Born the son of an architect in London, England, Young attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and made his stage debut in 1908, his Broadway debut four years later, and after serving (with the U.S. Army, interestingly enough) in World War I, his movie debut in 1922, playing Watson to John Barrymore‘s Sherlock Holmes.

But it was in talkies that Young really found his stride. He excelled at playing upper crust types, with his neat little mustache and his fumbling, mumbling way of speaking, and so, though he would play the occasional dramatic part (and very ably, too) over the course of his movie career, it was in romantic and screwball comedies that he truly made his mark.

Roland Young is perhaps best remembered for his portrayal of the henpecked Cosmo Topper in the popular Topper series of pictures, but his roster of credit includes a number of top-notch comedies, among them One Hour with You (1932), Ruggles of Red Gap (1935), The Philadelphia Story (1940), and Tales of Manhattan (1942), but even in lesser known films, he shines.

Young also worked in radio, starring in a 1945 summer replacement series based on the Topper movies and guesting on other programs, and on television, including such programs as Lux Video Theatre, Studio One, Pulitzer Prize Playhouse and The Chevrolet Tele-Theatre.

Young died of natural causes at age 65 in his NYC apartment on June 5, 1953.

Here’s to you, Mr. Young. Thanks for the laughs!