Here are 10 things you should know about Florence Rice, born 116 years ago today. After enjoying success on Broadway, she worked steadily in films over a brief Hollywood career.

Tag: Jeanette MacDonald

10 Things You Should Know About Tom Helmore

Here are 10 things you should know about Tom Helmore, born 119 years ago today. He enjoyed a successful stage and screen career in England before coming to the U.S. in 1945.

10 Things You Should Know About Gene Raymond

Here are 10 things you should know about Gene Raymond, born 114 years ago today. He was a child actor who managed to continue his career into adulthood, on Broadway, in pictures and on television.

Snapshot in Prose: Jeanette MacDonald

Jeanette MacDonald is best remembered today for the old-fashioned (even then) musicals she made with Nelson Eddy, but you’d be hard-pressed to get us to watch one of those. We greatly prefer the movies she made in the early Thirties—most notably with director Ernst Lubitsch—when she was allowed to show a little spark and sass on screen.

This profile originally saw the light of day in September 1940. Her professional pairing with Eddy was already well established, and she had been married to actor Gene Raymond for three years. She and Raymond remained married until MacDonald’s death in 1965.

The Private Letters of Jeanette MacDonald

The correspondence of a

movie star covers dozens

of different matters. Here

is your chance to spend a

day at Jeanette’s desk and

see how she deals with

this important problem.

By SONIA LEE

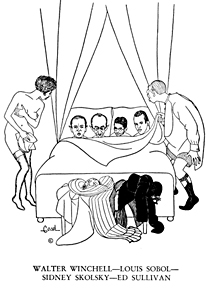

In Your Hat, pt. 5

Here’s Chapter 5 of In Your Hat, the 1933 tell-all memoir by Hat Check Girl to the Stars, Renee Carroll, in which she dishes on 1930s press agentry and Broadway columnists such as Walter Winchell, Louis Sobol, Mark Hellinger, and others.

THE press boys are divided into two sections. Those who are in and those trying to get in. Those already in are such lights as Winchell, Hellinger, Sobol, Skolsky, Yawitz, Sullivan and the rest. On the other side of the gate, trying day and night to crash it, are a host of diligent workers, most of them intelligent youngsters who have experienced softening of the brain.

The press agents, who like to think of themselves as connected with the newspaper business, are in such great numbers that it would be difficult to name them all. But the majority of the best ones are connected with the films.

The press agents, who like to think of themselves as connected with the newspaper business, are in such great numbers that it would be difficult to name them all. But the majority of the best ones are connected with the films.

It has been said that if you scratch a star you’ll find a press agent, and if you scratch a press agent, he’ll thank you. The press agent is a nervous, erratic type who works in twenty-four hour shifts (while you sleep) and succeeds in bringing the name of his client before the public—or gets thrown into the street in the attempt. If you walk along and see a man dusting himself off, you can lay odds it’s a press agent with another idea gone wrong.

The reason I say that most press agents are in the preliminary stages of dementia praecox is because they write things that under ordinary circumstances they would admit were insane, and yet they expect editors to print the stuff without question. Their efforts are so frantic that in no time at all they get farfetched and nutty, and the result is shown partly in the collection of press-agent’s squibs that I have collected from time to time. All of the copy is from movie press agents gone wrong.

For example, one of them, having nothing else to do, will write a story and send it to the editors expecting them to print it. This one is an extract of a story sent from Hollywood:

“…the physical measurements of 124 of the chorus girls under contract to this studio reveal that they have grown, on an average, one-fourth of an inch in height in the past eight months since most of them were placed under contract. There has also been an average of increase of three pounds in weight despite the strenuous dancing which is part of their daily routine.”

This startling item may make the nation growth-conscious and it may, on the other hand, make the press agent obnoxious.

Another great news break for managing editors comes printed in sotto voce type, telling the gaping world that an English actor who appeared as a butler in many films “has received letters offering him jobs as the major-domo in the service of many Park Avenue dowagers.” It goes on to say that the actors has received 279 offers.

Another story teller sends out a squib saying that love scenes have not suffered with talking films, for a hero and a heroine meeting for the first time on the set no longer find it necessary to simulate warmth in their celluloid caresses. Science has come to Cupid’s assistance in the guise of a portable set-warmer, which sends gales of hot air into chilly stages. SIZZLING LOVE SCENES ARE BECOMING A REALITY AT TALKIE STUDIOS! (The capital letters are the press agent’s.) Operated by gas and electricity, the heating units, etc. An electric fans blows hot air in any desired direction.

They might have saved expenses and put the writer on the scene.

Read More »