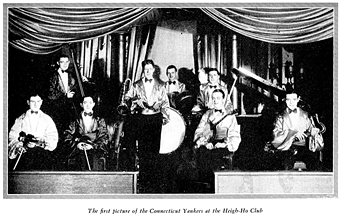

In Chapter Two of Rudy Vallée’s 1930 memoir, Vagabond Dreams Come True, we’re there as Vallée’s band of musicians begin the engagement that would bring them fame and acclaim, at NYC’s Heigh-Ho Club.

THE YANKEES MEET

I was not a bit hurt when I saw the change of expression that came over the faces of the five boys who did not know me, because I realize only too well that I do not look like an orchestra leader. The other two, Cliff Burwell and the tenor saxophonist, Joe Miller, had played with me and knew that I had some ideas and liked my work. I had played many engagements with Cliff Burwell at the Westchester Biltmore during my college years. In fact, I regarded his pianistic ability so highly that had I been unable to secure him I would not have taken the Heigh-Ho engagement.

To me the piano is the and soul of the orchestra, without which you have nothing. And as I had for a long time had the idea in my head which I was now about to put into practice, I knew I would need a pianist who knew his keys thoroughly, and had a good memory for old pieces; one who could learn new pieces quickly, could play a tune in any key and, above all, could take piano choruses alone with only the drum accompanying him and play them in a way that would sound like four hands at the piano.

To me the piano is the and soul of the orchestra, without which you have nothing. And as I had for a long time had the idea in my head which I was now about to put into practice, I knew I would need a pianist who knew his keys thoroughly, and had a good memory for old pieces; one who could learn new pieces quickly, could play a tune in any key and, above all, could take piano choruses alone with only the drum accompanying him and play them in a way that would sound like four hands at the piano.In all my dance orchestra experience I had played with the best of pianists. In London, our pianist was England’s best. The American with whom I had sailed to London, who was one of America’s greatest. The men I played with while at Yale were the best. I had become quite spoiled, and since this was the first band of my own, I felt that to start with a poor pianist would be to whip me before I began.

I had wired Burwell, who was in New Haven, playing very little as work was at a standstill. He was a wonderful man who had never been sufficiently featured and brought out where the public could appreciate his marvelous artistry. Today I think he thanks me for doing just that. I was very greatly relieved when he wired back that he would come, and that he could also secure Joe Miller, the tenor saxophone who lived near him and to whom I had also wired.

The rest of the men were strange to me.

There was Ray Toland, drummer, six and one half feet tall, size fifteen shoes. For several years he had played with Mannie Lowy, our first violinist, who has a wonderfully sweet tone and a loyal and energetic personality.

Next came Charlie Peterson, our banjoist, who came in from the middlewest with a Minnesota accent and the taste of several colleges; good-natured and always day-dreaming.

Then there was Harry Patent, our little bass player, quite as devoted to the study of music as my pianist. Harry had played the violin in junior symphonies and had decided to take up the string bass at the age of seventeen. He had practiced long and faithfully but had failed to secure an engagement anywhere, because he looked too young; so he conceived the bright idea of growing a mustache, which did indeed lend him an air of sophistication. Someone had recommended him to us and we gave him his first opportunity. Today he is rated as one of the world’s finest string bass players and has never failed to evoke admiration from other musicians.

Finally came one of the boys who is the bane of my existence and at the same time a great personality. With a name like Jules De Vorzon you would look for no less than one of the descendants of the old Canadian fur trappers who would have difficulty in eliminating a “Canuck accent”; instead you find a pop-eyed individual whose face is a puzzle. He might be Italian, or French, or even Jewish, which he really is. Jules—always late, always making engagements at the last minute; wrapped up in his girl whom he loves more than life itself—but little Jules, irrepressible, buoyant, with a vitality that expresses itself in a thousand ways that always brings a smile and an invitation to the tables of our guests.

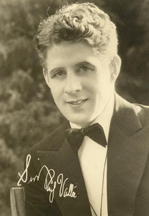

These were my recruits, and I saw they looked at me in a disappointed sort of way because that is the first reaction of the average person who sees me for the first time. My appearance was never calculated to inspire awe or respect in anyone. It has given me a great humorous kick, when, in the course of our vaudeville engagements, we have gone to the stage door of a new theatre to find our dressing rooms and the stage door man has invariably said to me, “When will Mr. Vallée be here?