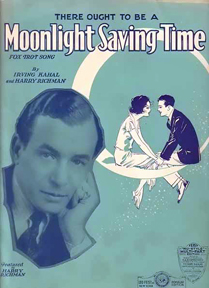

We’re awfully fond of the Harry Richman–Irving Kahal tune, (There Oughta Be a) Moonlight Saving Time, and we invariably think of it on this day every spring.

We’re awfully fond of the Harry Richman–Irving Kahal tune, (There Oughta Be a) Moonlight Saving Time, and we invariably think of it on this day every spring.

It was recorded by a wide variety of artists and orchestras when it debuted back in 1931, from Ambrose and His Mayfair Hotel Orchestra to Maurice Chevalier, Guy Lombardo and His Royal Canadians, and Jay Wilbur’s Hottentots, but our favorite rendition, in large part because she sings the verses as well as the chorus (unlike most of the other artists who have recorded, back then and in the years since) is by Cladrite Radio sweetheart Annette Hanshaw, who recorded the song in New York City on May 9, 1931, accompanied by Jimmy Dorsey on clarinet, Sammy Prager on piano and Eddie Lang on guitar.

Our gal Annette’s performance of the song manages to be simultaneously playful, sincere and just a little bit saucy, which shouldn’t be surprising. She was a terrific singer, and it’s a catchy and clever song. Enjoy!

(There Oughta Be a) Moonlight Savings Time

Birdies fly with new ambition,

Spring is in their song.

Soon you’ll find yourself a-wishin’

Days were not so long.

If my thought is not defined,

Listen while I speak my mind:There oughta be a moonlight saving time

So I could love that boy o’ mine

Until the birdies wake and chime ‘Good morning!’There oughta be a law in clover time

To keep that moon out overtime,

To keep each lover’s lane in rhyme till dawning.You’d better hurry up, hurry up

Hurry up, get busy today.

You’d better croon a tune, croon a tune

To the man up in the moon,

And here’s what I’d say:There oughta be a moonlight saving time

So I could love that boy of mine

Until the birdies wake and chime ‘Good morning!’In January, the nights are very long

But that’s all right.

In happy June comes the honeymoon time;

Days are longer than the nights.In lovetime season, the moon’s the reason

For every cuddle and kiss.

When days are longer, the nights are shorter.

Something should be done about this.Oh, there oughta be a moonlight saving time

To make the morning glories climb

An hour later on the vine each morning.You sorta need a moon to bill and coo,

An old back porch, a birch canoe.

A parlor lamp in June won’t do, I’m warning.I’ve heard the farmer say, ‘I’ll make hay

While the sun is shining above.’

But when the day is done, night’s begun;

You can ask the farmer’s son, it’s time to make love.There oughta be a moonlight saving time

So I could love that boy of mine

Until the birdies wake and chime ‘Good morning!’

Words by Irving Kahal; music by Harry Richman—1931