Alton Glenn Miller was born 112 years ago today in Clarinda, Iowa. His family moved around a bit, to Nebraska and Missouri, before finally settling in Fort Morgan, Colorado, where Glenn attended high school. Having picked up the trombone in his junior high years (after dabbling with the cornet and the mandolin), he formed his first dance band with some fellow students, and by the time he had graduated from high school in 1921, he had his sights set on a career in music.

Miller attended the University of Colorado but devoted so much time to his pursuit of a musical career that his attendance (and, as one might expect, his grades) suffered. He finally dropped out of school, studied with the renowned musical composition theorist Joseph Schillinger and went on to play with a number of orchestras, led by such names as Ben Pollack, Victor Young, Nat Shilkret, Red Nichols and the Dorsey Brothers. He also played in the pit bands for two hit Broadway shows, Strike Up the Band and Girl Crazy.

In addition to playing trombone with the Dorseys, Miller served as arranger and composer, two roles in which he’d go on to have great success. In 1935, he organized an orchestra for British bandleader Ray Noble that included such later-prominent names as Claude Thornhill, Bud Freeman and Charlie Spivak. The orchestra appeared in the 1935 Paramount picture The Big Broadcast of 1936, marking Miller’s first appearance on the big screen.

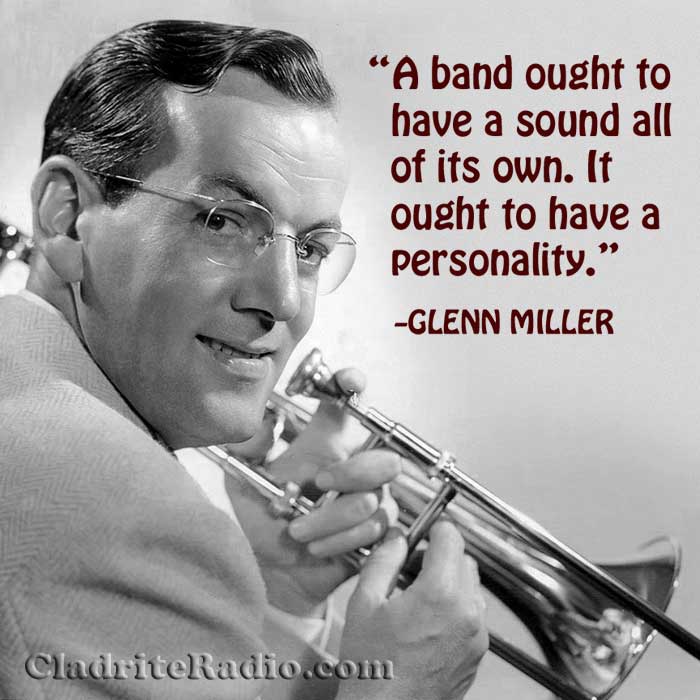

Miller formed his own orchestra for the first time in 1937, but it lacked a distinctive sound and didn’t last long. Back in New York, he set about coming up with a sound that would be his and his alone. He did so by having the clarinet and tenor saxophone play the melodic line, while three other saxes played in close harmony (we think we’ve got that right—no arrangers, we!). The trick to it was using Wilbur Schwartz, a saxophonist, to play that clarinet. Schwartz had a fuller sound than many clarinet players didn’t, and that was what set the Miller orchestra apart. As Miller himself once put it, “The fifth sax, playing clarinet most of the time, lets you know whose band you’re listening to. And that’s about all there is to it.”

In the spring of 1939, the Glenn Miller Orchestra had a successful rusn first at the Meadowbrook Ballroom in Cedar Grove, New Jersey, and, more famously, at the Glen Island Casino in New Rochelle, New York, where they drew 1,800 patrons on opening night. Soon thereafter, the band’s record sales took off, beginning a long string of hit tracks that are still familiar today. Later that year, Time magazine observed that, of the 12 to 24 discs in each of the country’s 300,000 jukeboxes, between two and six were usually Miller’s.

From 1939 to 1942, the Miller outfit had its own quarter-hour radio show, sponsored by Chesterfield cigarettes, that aired three times a week. They also appeared in a pair of 20th Century Fox pictures, Sun Valley Serenade (1941) and Orchestra Wives (1942). A third film, Blind Date, was never made, due to Miller’s entry into the Army.

Miller’s sound was tightly arranged and well rehearsed, and jazz critics of the day (and since) have sometimes been harsh in their assessments of the group, but Miller didn’t care. He knew just the sound he wanted and insisted he didn’t view the orchestra as a jazz ensemble. The critics may have carped, but the public loved the orchestra’s music (and does to this day).

At the peak of his popularity in 1942, Miller pulled strings to be accepted into the Army (at 38, the Navy felt he was too old). He was made a captain (later promoted to major), and after being transferred to the Army Air Forces, set about to entertain the troops with his special brand of swinging sounds. He formed a 50-piece band and took it to England in the summer of 1944, where it performed some 800 times. The orchestra even made some recordings at the famed Abbey Road studios. Of Miller’s efforts to entertain the U.S. and Allied troops, General Jimmy Doolittle once said, “Next to a letter from home, that organization was the greatest morale builder in the European Theater of Operations.”

On December 15, 1944, Miller was to travel from Bedford, England, to Paris, France, to entertain troops there. His plane, carrying Maj. Miller, Lt. Col. Norman Baessell and pilot John Morgan, went down over the English Channel and was never recovered. The cause of the crash is said to have been a faulty carburetor. Miller was survived by his wife, Helen, and their adopted children, Steven and Jonnie; he was mourned by millions of adoring fans around the world. Miller was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star in 1945.

The list of Miller’s enduring hits is a long one: In the Mood, Moonlight Serenade, Chattanooga Choo-Choo, A String of Pearls, Pennsylvania 6-5000, (I’ve Got a Gal in) Kalamazoo, and so many more.

Happy birthday, Major Miller, wherever you may be!