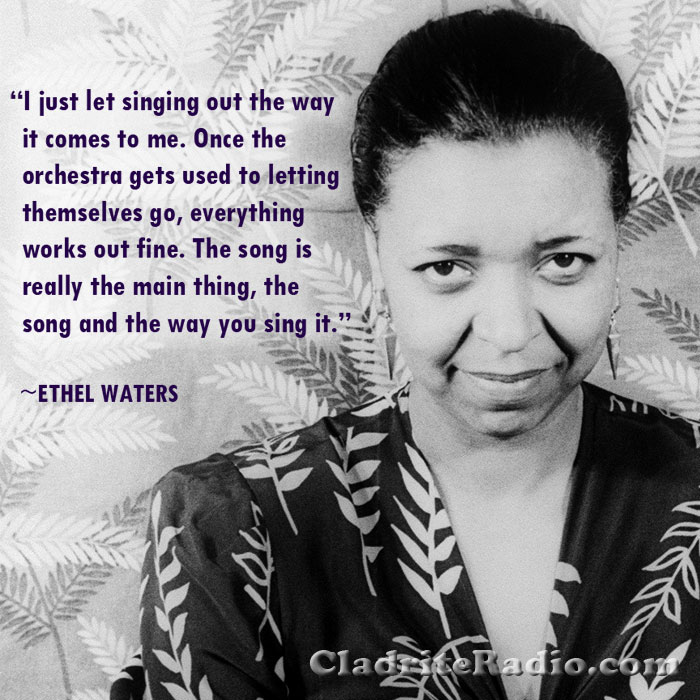

Singer and actress Ethel Waters was born in Chester, Pennsylvania, 120 years ago today. Here are 10 EW Did-You-Knows:

- Ethel’s mother was a teenage rape victim, and hers was a difficult childhood. She was raised in poverty and she never lived anywhere more than 15 months. “I never was a child,” she would say later. “I never was cuddled, or liked, or understood by my family.”

- Waters married at 13, but the man she married abused her and she left him to become a maid at a hotel in Philadelphia. When she was 17, she sang two songs at a costume party at a nightclub and was such a hit that she was offered work performing at the Lincoln Theatre in Baltimore.

- That engagement launched Waters’ career on the black vaudeville circuit. In Atlanta, she found herself working at the same club as blues legend Bessie Smith, who insisted that Waters not perform the same kind of music she was, so during their time on the same bill, Smith sang the blues and Waters stuck to popular songs.

- In 1919, Waters made her way to Harlem, debuting at a black club there called Edmond’s Cellar.

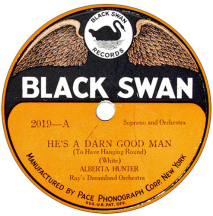

- In 1921, Waters became the fifth black woman to make a record on the small Cardinal label. Before long, she moved up to Black Swan Records, where she recorded with Fletcher Henderson. In 1925, she signed with Columbia records, for whom she recorded the hit song, Dinah (in 1998, that recording was given the Grammy Hall of Fame Award, one of three such awards Waters’ 1920s recordings received).

- As her star continued to rise, Waters began to play “white” vaudevile on the Keith Circuit, which paid more and increased her fame.

- In 1929, Waters introduced the Harry Akst song, Am I Blue? It was a huge hit for her and became her signature song.

- In the early 1930s, Waters starred at the Cotton Club and appeared in Irving Berlin’s hit musical revue As Thousands Cheer; she was the first black woman to appear in an otherwise all-white show.

- In 1933, Waters was, thanks to her continuing nightclub work, her stage success and her national radio program, the highest paid performer on Broadway.

- In the 1940s, Waters’ career was on the wane and she experienced legal and health problems. In 1951, she wrote her autobiography, His Eye Is on the Sparrow with Charles Samuels. A later memoir, To Me, It’s Wonderful, established her birth year as 1896; she’d been lying about her age for some time in order to get a group insurance policy.

- In her later years, Waters began to focus on gospel music and spirituals, often touring with evangelist Billy Graham. In 1983, she was posthumously inducted into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame.

Happy birthday, Ethel Waters, wherever you may be!