THE GHETTO GIRL

Tag: D.W. Griffith

Hollywood History 101

What more appropriate venue for a seven-hour history of Hollywood than Turner Classic Movies, the network that has devoted itself to celebrating and preserving classic motion pictures, from the silent era forward?

Moguls and Movies Stars: A History of Hollywood comprises a series of one-hour documentaries, covering seven key periods in the history of Hollywood, with a new chapter premiering each Monday at 8 p.m. ET and repeating the following Wednesday at the same time.

Moguls and Movies Stars: A History of Hollywood comprises a series of one-hour documentaries, covering seven key periods in the history of Hollywood, with a new chapter premiering each Monday at 8 p.m. ET and repeating the following Wednesday at the same time.

The chapter titles tell it all: Peepshow Pioneers, which airs on Monday night with a repeat on Wednesday evening, explores the origins of the motion picture and the earliest days of the movie industry, with a focus on Thomas Edison’s role in the rise of motion pictures. The Birth of Hollywood, which airs Monday and Wednesday of next week, explores how the American film industry, originally scattered across the country with a concentration of production companies in the New York City area, came to coalesce in Southern California, specifically a sleepy suburb to the north of Los Angeles called Hollywood.

We were fortunate enough to attend a screening of those first two chapters at NYC’s Film Forum, with TCM host Robert Osborne on hand to introduce the screening, and we can tell you that we can’t wait to see the remaining five chapters, so impressed were we with the first two.

Cinéastes familiar with the history of Hollywood probably won’t encounter a great deal of material in Moguls and Movie Stars with which they’re unfamiliar, but let’s face it—real movie buffs never tire of these stories, and the documentaries include a good deal of rarely seen footage and photographs and, yes, the occasional nugget of info that will come as news to even the most devoted movie fan. And more casual fans of classic movies with a desire to know more about the early days and Golden Age of Hollywood will find these documentaries compelling and informative.

Four-time Emmy nominee Jon Wilkman directed, wrote and produced the series, Christopher Plummer ably provides the narration, and an impressive array of film historians contribute on-camera insights and information.

But don’t take our word for it. Tune in at (or set those DVRs for) 8 p.m. ET tonight, and see for yourself. We suspect you’ll be hooked and will want to catch all seven chapters.

And TCM follows the debut of Peepshow Pioneers, with a collection of Edison films at 9 p.m., a re-airing of Peepshow Pioneers at 11 p.m., a collection of D.W. Griffith’s Biograph films at midnight, the films of Georges Melies at 2 a.m., seven silent shorts based on the plays of William Shakespeare at 4 a.m., and a Mary Pickford short drama, Ramona, at 5:30 a.m. (If any of those names are unfamiliar to you, they won’t be after watching Episode One.)

It’s a great chance to immerse yourself in the work of the very pioneers featured in the first episode of Moguls and Movie Stars.

How to succeed in Hollywood, ca. 1921

Mae Marsh was a movie star whose heyday occurred in the era of silent pictures. She appeared in more than 100 pictures before 1928, including D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) and The Birth of a Nation (1915), and made another 90 or so once the switch had been made to talking pictures.

Mae Marsh was a movie star whose heyday occurred in the era of silent pictures. She appeared in more than 100 pictures before 1928, including D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) and The Birth of a Nation (1915), and made another 90 or so once the switch had been made to talking pictures.

In 1921, in response, she claimed, to thousands of requests for advice from her fans, she authored a short book, “Screen Acting” that is one part memoir and two parts instruction book for those hoping to find work acting on the screen.

We were particularly intrigued (and, we’ll admit, amused) by the book’s third chapter, in which Ms. Marsh addresses, among other salient matters, the need for actors to be , er, clean-living and pure of heart and mind.

Does that describe the Hollywood of legend and lore? No, bless Ms. Marsh’s earnest heart.

Chapter III

Seven qualities that indicate fitness for a screen career

—Why they are important—An illustration of vitality.

As I have said, I have been asked by thousands of correspondents for the formula for screen success. I have never felt able to answer. I don’t believe there is any such formula.

Putting the proposition another way: If I were requested to choose from among ten beginners the one who would go farthest in motion pictures I should unhesitatingly lay my finger upon the one who possessed the following qualifications:

(1) Natural talent.

(2) Ambition.

(3) Personality.

(4) Sincerity.

(5) Agreeable appearance.

(6) Vitality and strength.

(7) Ability to learn quickly.I’m sure I would not go far wrong if I were to place my trust in one endowed with these qualities.

A natural talent for acting implies more than a mere desire to act. It is the art, usually discovered during childhood, of mimicry, and the joy in that art.

How many of us have been convulsed in our earlier years at some school girl friend’s take-off of our teacher? I seem to remember that in my grammar school days I was called upon more or less to take-off one of our teachers.

If not called upon I volunteered. None of my school chums got more enjoyment out of my “imitation of Miss Blank” than I did. I never dreamed at that time —or, if I did, they were vague dreams—that I was to become an actress. Since then I have come to the conclusion that I was actually taking my first steps toward what I chose as a career.

Natural talent, as I have called it, is no more than a tendency toward, or an aptitude for, some form of endeavor. In youth my first artistic loves were for mimicry and painting—the latter of which took the form of sculpturing—and both of these loves have been enduring.

For that reason unless my candidate for screen success previously shown some love for acting or mimicry I should come to the conclusion that he or she was intoxicated merely with the glamour of the profession, with no especial love for the fundamental thing itself.

This is an important point. If its significance were duly impressed upon the thousands of girls and boys, who would like to choose the screen for a career, perhaps, some of them would abandon their dreams and turn to things for which they have displayed some natural aptitude.

Ambition must, of course, go hand in hand with natural talent. In any form of vocational training it is assumed that the student has a feverish desire to succeed in the particular line that he has elected to follow. It is the same on the screen.

Possibly I might have written down enthusiasm in place of ambition. After one has attained stardom and thus, perhaps, achieve his or her ambition the ability sustain enthusiasm in one work becomes more important than ambition. But ambition and enthusiasm are closely correlated.

They mean that one has an ambition to gain the top, and that to reach that position one has the enthusiasm to practice all the forms of self-denial, discipline and study that are important to artistic success in any line.

Personality is important for the reason that the camera has a way of registering it unerringly. It is keen in detecting the weak or vapid.

In my eight years before a motion picture camera I have never met a person of inferior fibre whose inferiority was not accentuated by the camera. For that reason to sustain success on the screen I believe there is nothing more important than clean thoughts and clean living. They do register.

It is precisely the same with sincerity. In any line there is probably little hope for those who lack this salient quality. But a motion picture camera seems especially to delight in exposing insincerity.

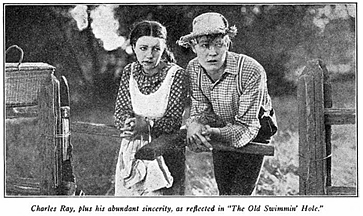

I think considerable of the success of Mary Pickford and Charles Ray—to name but two stars—is due to their absolute and abundant sincerity. The camera, finding so much that is clean and real, has joyously reproduced it. It is the love that Miss Pickford radiates from the screen and the obvious manliness of Mr. Ray that are among their biggest assets. This is sincere love and sincere manliness, or it would never been so emphasized by the camera.

My candidate for screen honors, therefore, must have the God-given quality of sincerity. Only that kind can feel deeply, think cleanly and develop the sterling traits without which neither a camera or a public can be very long deceived.

I now come to the matter of personal appearance. This is a topic in which every man under 65, and every woman under 100 years seem interested. I sometimes wonder if it is not the desire to see how they would look on the screen, rather than how they might act, that fills so many boys and girls and men and women with an ambition for a screen career.

I have found the subject of such universal interest that I believe it deserves a chapter to itself. Therefore I shall dismiss this matter until the next. I may say, however, that in my candidate I should rank agreeable appearance and an expressive face as superior to mere beauty.

To paraphrase, nothing succeeds like good health. Of itself it is the most valuable thing that we should own. Good health can be translated into terms of capacity for work. Therefore since a screen career means both hard and trying work I should insist that my candidate possess or develop the qualities of strength and vitality.

I am aware that in my forms of art such artists as Chopin, Stevenson and Milton, have become famous in spite of great physical handicaps. I do not believe the same can be done in pictures.

It seems to me that healthy persons like to see and be among well people. Motion picture audiences being invariably in first-class physical shape themselves, desire that those who appear before them on the screen be likewise fortunate. It is my belief that an audience is usually bored to tears by a convalescing hero or heroine. If I were in charge of all the played I should cut such episodes very short. They beget more impatience than sympathy.

But it is not only because good health radiates from the screen that is important. In point of nervous and muscular strain, and the often long studio hours that are necessary when production has begun, good health is essential.

To illustrate: While we were filming “Polly of the Circus” in Fort Lee one morning I reported at the studio at nine o’clock. We were working on some interior scenes that were vital to the success of the story. My director at that time was Mr. Charles Horan. Mr. Vernon Steel was playing the male lead.

That day we became so engrossed in playing some rather delicate scenes that before we knew it—or at least before I could realize it—it was six o’clock and we weren’t half done.

“What do you say to continuing?” asked Mr. Horan.

“Good; we’re right in the spirit of it,” I replied. We had a bite to eat and worked on until midnight. In spite of our hard and earnest efforts there were several scenes with which we were dissatisfied.

“Well,” said Mr. Horan ruefully. “Tomorrow will be another day.” As he spoke it dawned on me how one of the scenes on which we felt we had failed could be done with probable success.

“Why tomorrow?” I replied. “Let’s make a night of it if necessary. We simply have to get that scene.”

Mr. Horan grinned. That had been his wish. But he had feared breaking the camel’s back.

We worked until four o’clock that morning. Things went swimmingly. It was broad daylight when I ferried across the Hudson but if I was very tired I was equally happy.

Several times during “Polly of the Circus” we had experiences which, in the number of hours put in, were similar to that which I have related. But in the end it was worth while. We had a picture.

At that time I was feeling in the best of health but, even so, the long hours had been a severe drain upon my none too great vitality. For anyone lacking strength and vitality such hours would have been impossible.

It is not my intention to write a booklet on health. But all of us should be very careful of our most precious possession. I know of so many young girls in motion pictures who have let their health get away from them. And some of the cases are so pitiful. . . .

My candidate, then, will have strength and vitality and, equally important, he or she will cling to both, whatever social sacrifices may have to be made to preserve them.

The ability to learn quickly will save anyone going into screen work so much trouble and possible humiliation that it may well be listed as an essential qualification.

The screen is no place for the mental laggard. The beginner, particularly, must be alive to learn the new lessons that each day will bring, and learning them he must remember.

During the course of production in a studio things are at high tension. Time is money. Each of us constitutes a more or less important cog in a great machine. Those clogs that inexcusably forget to function are eliminated.