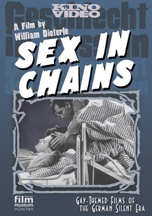

We took in a movie today, a 1928 German silent called Geschlecht in Fesseln (alternately titled in English “Sex in Chains” or “Sex in Fetters”—we prefer the latter), and it got us to thinking how long it can take for an idea to take hold, to become a part of the zeitgeist, if you will.

We took in a movie today, a 1928 German silent called Geschlecht in Fesseln (alternately titled in English “Sex in Chains” or “Sex in Fetters”—we prefer the latter), and it got us to thinking how long it can take for an idea to take hold, to become a part of the zeitgeist, if you will.

Let us give you the quick rundown on the picture’s plot (warning: there are many spoilers ahead): It’s Weimar Germany, and Franz Sommer (played by the picture’s director, William Dieterle) is out of work. He and his wife Helene are struggling to make ends meet, but he’s too proud to a) tell her father, who could probably help them out, or b) let Helene go to work (sheesh, if we only had a nickel for every old movie we’ve seen in which the husband was too prideful to agree to his wife get a job).

She finally sways him and takes a job as a cigarette girl at a beer garden. She’s fighting off an overly attentive customer one night when Franz pops in for a beer and a visit. She tells Franz of her struggles with the customer, and when Franz witnesses the customer grabbing Helene, he hurries over and pops the customer in the nose.

Of course, the customer hits his head on a rock and is near death, which lands Franz in the pokey. Eventually, the customer dies and Franz is sentenced to three years in prison.

In jail while being tried, Franz meets an industrialist, Rudolf Steinau, who is being acquitted of a crime even as Franz is being convicted. As Steinau is freed, he vows before Franz that he will be a tireless advocate for the cause of prison reform, especially for the practice of allowing convicts more quality time—even conjugal visits—with loved ones. He also promises Franz to take care of Helene until Franz is released.

In jail while being tried, Franz meets an industrialist, Rudolf Steinau, who is being acquitted of a crime even as Franz is being convicted. As Steinau is freed, he vows before Franz that he will be a tireless advocate for the cause of prison reform, especially for the practice of allowing convicts more quality time—even conjugal visits—with loved ones. He also promises Franz to take care of Helene until Franz is released.

Franz, now in prison, is taking it hard. In fact, all the inmates are taking it really hard. In their craving for the good loving they’re missing while away from their spouses, they resemble the crazed, pop-eyed drug addicts in the 1930s exploitation film Reefer Madness. (We’ve spent no time in prison, knock on wood, but we’ve nonetheless managed to go without sex for weeks, even months, at a time without so very much duress, so this aspect of this picture seemed more than over the top to us—but we digress.)

Helene misses her Franz, too, and at one point she too appears crazed and out of control. In this state, she shows up at Steinau’s door, and, though he tries to resist, in the end, he succumbs to her addled advances.

Helene misses her Franz, too, and at one point she too appears crazed and out of control. In this state, she shows up at Steinau’s door, and, though he tries to resist, in the end, he succumbs to her addled advances.

Poor desperate Franz, meanwhile, has been successfully wooed and won by an attractive young man who shares his cell.

When Franz is finally released from prison, both he and Helene are wracked with guilt. They reveal their indiscretions and reaffirm their mutual devotion, but so ridden are they with shame that they turn on the gas in their apartment and end their lives in melodramatic fashion.

The story is presented as being based on the findings of a German social scientist of the day (his name escapes us), who himself spent eight years in prison and so knew whereof he spoke. This scientist, like the character Steinau, was an advocate for prison reform, calling for conjugal visits for the incarcerated.

It happens sometimes when watching an old movie that we are suprised to find a particular school of thought already at play or a now-familiar invention in the works, long before we might have imagined it. One will, if one watches enough early-to-mid 1930s movies, come across a character mention the pending arrival of television. We know that TV was delayed by World War II, but it’s still a little jarring to hear it mentioned in a 1930s picture.

And in certain 1950s and ’60s movies, car phones are depicted and telephone answering machines, and we find ourselves asking, “If these products were available then, what took so long for them to become widely available or, at least, widely popular?”

And, as with the abolition of slavery in the U.S. or the suffrage movement, it’s hard to imagine the idea of conjugal visits taking so long to get traction in society. We were surprised that the idea was already being promoted as long ago as 1928, given that the practice has become common only relatively recently. Change comes slowly, it seems.